膵臓腺癌の腫瘍微小環境を調べるための近位液の分離

Summary

膵液は、ヒト膵臓がんのバイオマーカーの貴重な供給源です。ここでは、術中収集手順の方法について説明します。マウスモデルでこの手順を採用するという課題を克服するために、代替サンプルである腫瘍間質液を提案し、ここではその分離のための2つのプロトコルについて説明します。

Abstract

膵臓腺癌(PDAC)は、癌関連の死因の4番目に多い原因であり、まもなく2番目になります。術前の鑑別診断と患者のプロファイリングを支援するために、特定の膵臓の病状に関連する変数が緊急に必要です。膵液は比較的未踏の体液であり、腫瘍部位に近接しているため、周囲の組織の変化を反映しています。ここでは、術中の収集手順について詳しく説明します。残念ながら、膵液採取をPDACのマウスモデルに変換して機構研究を行うことは、技術的に非常に困難です。腫瘍間質液(TIF)は、腫瘍細胞と間質細胞を浸す血液と血漿の外側の細胞外液です。膵液と同様に、血漿中で希釈された分子を収集して濃縮する特性のために、TIFは微小環境変化の指標として、また疾患関連バイオマーカーの貴重な供給源として利用することができる。TIFは容易にアクセスできないため、TIFを分離するための様々な技術が提案されている。ここでは、その単離のための2つの簡単で技術的に要求の厳しい方法、すなわち組織遠心分離と組織溶出について説明します。

Introduction

膵管腺癌(PDAC)は最も攻撃的な腫瘍の1つであり、まもなく2番目に多い死因になります1,2,3。免疫抑制性の微小環境と免疫療法プロトコル4に対する無反応でよく知られています。現在、外科的切除は依然としてPDACの唯一の治癒選択肢ですが、早期再発や術後合併症の頻度は高くなっています。進行期までの特定の症状の欠如は早期診断を可能にしず、疾患の期限に寄与する。さらに、PDACと他の良性膵臓病理との間の症状の重複は、現在の診断戦略による迅速で信頼性の高い診断の達成を妨げる可能性がある。特定の膵臓の病状に関連する変数を特定することで、外科的意思決定プロセスを促進し、患者のプロファイリングを改善する可能性があります。

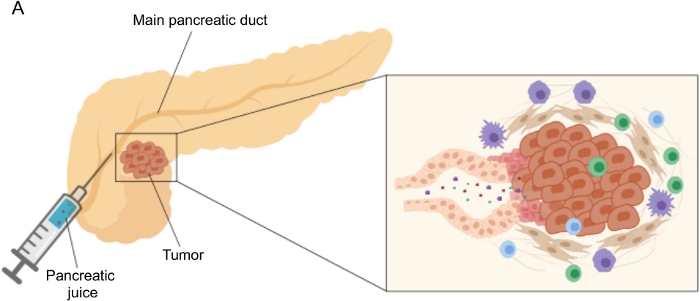

バイオマーカーの発見における有望な結果は、血液5,6,7、尿8、唾液9、膵液10,11,12などの容易に入手しやすい体液を使用して達成されています。多くの研究では、ゲノム、プロテオミクス、メタボローム技術などの包括的な「オミクス」アプローチを利用して、PDACと他の良性膵臓疾患を区別できる候補分子またはシグネチャを特定しています。私たちは最近、比較的未踏の体液である膵液を使用して、異なる臨床プロファイルを持つ患者の代謝シグネチャを特定できることを示しました12。膵液はタンパク質が豊富な液体で、膵管細胞の分泌物を蓄積し、主膵管に流れ、次に主総胆管に流れます。膵臓に近接しているため、腫瘍塊によって引き起こされる微小環境の摂動の影響を強く受ける可能性があるため(図1)、血液や尿、または組織ベースのプロファイリングよりも有益です。いくつかの研究は、細胞学的分析13、質量分析によるプロテオミクス分析14,15、K-rasおよびp53変異16,17、DNAメチル化の変化18、およびmiRNA19を含むさまざまなアプローチを使用して、疾患の新しいバイオマーカーを特定するための膵液の可能性を調査してきました。.技術的には、膵液は、術中または内視鏡的超音波、逆行性胆管 – 膵造影などの低侵襲処置で、または十二指腸液分泌物の内視鏡的収集によって収集することができる20。膵液組成物が、使用される収集技術によってどの程度影響を受けるかはまだ明らかではない。ここでは、術中の収集手順について説明し、膵液がPDACバイオマーカーの貴重な供給源になり得ることを示します。

図1:膵液採取の模式図。 (A)手術中の膵管への膵液の分泌とその採取を示す模式図。挿入図は腫瘍微小環境のクローズアップを示しています:膵液は膵管内の腫瘍および間質細胞によって放出される分子を収集します。 この図の拡大版を表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

PDACの遺伝的および同所性マウスモデルにおける膵液の収集は、前臨床機構研究でこの生体液を利用するという観点から高く評価されます。ただし、この手順は技術的に非常に困難な場合があり、皮下腫瘍などの単純なモデルでは実行できません。このため、腫瘍間質液(TIF)は、周囲の摂動の指標として機能するという同様の特性から、膵液の代替源として同定されました。間質液(IF)は、細胞外液であり、血管およびリンパ管の外側に見られ、組織細胞21を浸すものである。IF組成は、臓器への血液循環と局所分泌の両方の影響を受けます。実際、周囲の細胞はIF21でタンパク質を活発に産生および分泌します。間質は周囲の組織の微小環境の変化を反映しているため、腫瘍などのいくつかの病理学的状況におけるバイオマーカー発見の貴重な情報源となる可能性があります。TIF中の高濃度の局所分泌タンパク質は、血漿中の予後または診断バイオマーカーとして試験される候補分子を同定するために使用することができる22、23、24。いくつかの研究は、TIFが質量分析技術23、24、25、マルチプレックスELISAアプローチ26、およびマイクロRNAプロファイリング27などのハイスループットプロテオミクスアプローチに適したサンプルであることを証明しています。

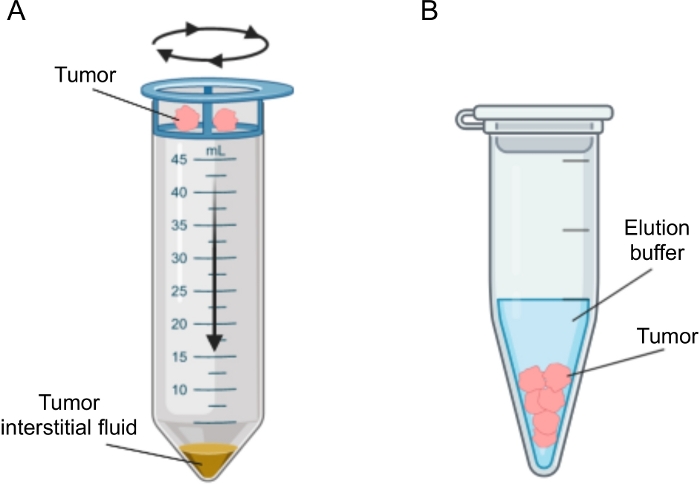

腫瘍におけるIFの単離のためにいくつかのアプローチが提案されており、これはde vivo(毛細血管限外濾過28、29、30、31および微小透析32、33、34、35)およびex vivo法(組織遠心分離22、36、37、38および組織溶出39,40,41,42)。これらの技術は、広範囲に詳細に検討されている43,44。適切な方法の選択では、下流の分析とアプリケーション、回収量などの問題を考慮する必要があります。私たちは最近、このアプローチを原理の証明として使用して、2つのマウス膵臓腺癌細胞株からの腫瘍の異なる代謝活性を実証しました12。文献24,38に基づいて、細胞内含有量からの細胞の破壊と希釈を避けるために、低速遠心分離法を使用することを選択しました。TIF中のグルコースと乳酸の両方の量は、2つの異なる細胞株の異なる解糖特性を反映していました。ここでは、TIFの単離に最も一般的に使用される2つの方法である組織遠心分離と組織溶出のプロトコルについて詳しく説明します(図2)。

図2:腫瘍間質液分離法の概略図。 プロトコル、すなわち組織遠心分離(A)および組織溶出(B)に詳細に記載された技術の概略図。この図の拡大版を表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

本研究では,術中に膵液を採取する技術について述べ,未踏の体液生検である.私たちは最近、膵液が疾患12の代謝マーカーの供給源として利用できることを示しました。血液5、6、7、尿8、唾液9などの他のリキッドバイオプシーのメタボローム分析は、PDACと健康な被験者?…

Divulgations

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

技術支援を提供してくれたロベルタ・ミリオレに感謝します。これらの結果につながる研究は、IG2016-ID.18443プロジェクトであるP.I.マルケシフェデリカの下で、イタリア協会(AIRC)から資金提供を受けています。資金提供者は、研究デザイン、データ収集と分析、出版の決定、または原稿の準備において何の役割も果たしていませんでした。

Materials

| 1 mL syringe | BD Biosciences | 309659 | |

| 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube | Greiner BioOne | GR616201 | |

| 20 µm nylon cell strainer | pluriSelect | 43-50020-03 | |

| 25G needle | BD Biosciences | 305122 | |

| 3 mL K2EDTA vacutainer | BD Biosciences | 366473 | |

| 3 mL syringe | BD Biosciences | 309656 | |

| 50 mL Falcon tube | Corning | 352098 | |

| Clamps | Medicon | 06.20.12 | |

| Disposable scalpel | Medicom | 9000-10 | |

| Fetal bovine serum | Microtech | MG10432 | |

| Flat-tipped forceps | Medicon | 06.00.10 | |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Lonza | ECB3001D | |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Sigma-Aldrich | D8537 | |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Roche | 34044100 | |

| RPMI medium | Euroclone | ECB9006L | |

| Scissors | Medicon | 02.04.09 | |

| Trypsin/EDTA 1x | Lonza | BE17-161F | |

| Ultraglutamine 100x | Lonza | BE17-605E/U1 |

References

- Costello, E., Greenhalf, W., Neoptolemos, J. P. New biomarkers and targets in pancreatic cancer and their application to treatment. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 9 (8), 435-444 (2012).

- Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 70 (1), 7-30 (2020).

- Neoptolemos, J. P., et al. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer: current and future perspectives. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 15 (6), 333-348 (2018).

- Sahin, I. H., Askan, G., Hu, Z. I., O’Reilly, E. M. Immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: an emerging entity. Annals of Oncology. 28 (12), 2950-2961 (2017).

- Mayerle, J., et al. Metabolic biomarker signature to differentiate pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma from chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 67 (1), 128-137 (2018).

- Bathe, O. F., et al. Feasibility of identifying pancreatic cancer based on serum metabolomics. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 20 (1), 140-147 (2011).

- Mayers, J. R., et al. Elevation of circulating branched-chain amino acids is an early event in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma development. Nature Medicine. 20 (10), 1193-1198 (2014).

- Napoli, C., et al. Urine metabolic signature of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by (1)h nuclear magnetic resonance: identification, mapping, and evolution. Journal of Proteome Research. 11 (1), 1274-1283 (2012).

- Sugimoto, M., Wong, D. T., Hirayama, A., Soga, T., Tomita, M. Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry-based saliva metabolomics identified oral, breast and pancreatic cancer-specific profiles. Metabolomics. 6 (1), 78-95 (2010).

- Chen, R., et al. Comparison of pancreas juice proteins from cancer versus pancreatitis using quantitative proteomic analysis. Pancreas. 34 (1), 70-79 (2007).

- Mori, Y., et al. A minimally invasive and simple screening test for detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma using biomarkers in duodenal juice. Pancreas. 42 (2), 187-192 (2013).

- Cortese, N., et al. Metabolome of Pancreatic Juice Delineates Distinct Clinical Profiles of Pancreatic Cancer and Reveals a Link between Glucose Metabolism and PD-1+ Cells. Cancer Immunology Research. , (2020).

- Tanaka, M., et al. Cytologic Analysis of Pancreatic Juice Increases Specificity of Detection of Malignant IPMN-A Systematic Review. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 17 (11), 2199-2211 (2019).

- Chen, K. T., et al. Potential prognostic biomarkers of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 43 (1), 22-27 (2014).

- Tian, M., et al. Proteomic analysis identifies MMP-9, DJ-1 and A1BG as overexpressed proteins in pancreatic juice from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients. BMC Cancer. 8, 241 (2008).

- Shi, C., et al. Sensitive and quantitative detection of KRAS2 gene mutations in pancreatic duct juice differentiates patients with pancreatic cancer from chronic pancreatitis, potential for early detection. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 7 (3), 353-360 (2008).

- Rogers, C. D., et al. Differentiating pancreatic lesions by microarray and QPCR analysis of pancreatic juice RNAs. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 5 (10), 1383-1389 (2006).

- Matsubayashi, H., et al. DNA methylation alterations in the pancreatic juice of patients with suspected pancreatic disease. Recherche en cancérologie. 66 (2), 1208-1217 (2006).

- Cote, G. A., et al. A pilot study to develop a diagnostic test for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma based on differential expression of select miRNA in plasma and bile. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 109 (12), 1942-1952 (2014).

- Yu, J., et al. Digital next-generation sequencing identifies low-abundance mutations in pancreatic juice samples collected from the duodenum of patients with pancreatic cancer and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Gut. , (2016).

- Wiig, H., Swartz, M. A. Interstitial fluid and lymph formation and transport: physiological regulation and roles in inflammation and cancer. Physiological Reviews. 92 (3), 1005-1060 (2012).

- Haslene-Hox, H., et al. A new method for isolation of interstitial fluid from human solid tumors applied to proteomic analysis of ovarian carcinoma tissue. PLoS One. 6 (4), 19217 (2011).

- Zhang, J., et al. In-depth proteomic analysis of tissue interstitial fluid for hepatocellular carcinoma serum biomarker discovery. British Journal of Cancer. 117 (11), 1676-1684 (2017).

- Sullivan, M. R., et al. Quantification of microenvironmental metabolites in murine cancers reveals determinants of tumor nutrient availability. Elife. 8, (2019).

- Matas-Nadal, C., et al. Evaluation of Tumor Interstitial Fluid-Extraction Methods for Proteome Analysis: Comparison of Biopsy Elution versus Centrifugation. Journal of Proteome Research. 19 (7), 2598-2605 (2020).

- Espinoza, J. A., et al. Cytokine profiling of tumor interstitial fluid of the breast and its relationship with lymphocyte infiltration and clinicopathological characteristics. Oncoimmunology. 5 (12), 1248015 (2016).

- Halvorsen, A. R., et al. Profiling of microRNAs in tumor interstitial fluid of breast tumors – a novel resource to identify biomarkers for prognostic classification and detection of cancer. Molecular Oncology. 11 (2), 220-234 (2017).

- Yang, S., Huang, C. M. Recent advances in protein profiling of tissues and tissue fluids. Expert Review of Proteomics. 4, 515-529 (2007).

- Huang, C. M., et al. Mass spectrometric proteomics profiles of in vivo tumor secretomes: capillary ultrafiltration sampling of regressive tumor masses. Proteomics. 6 (22), 6107-6116 (2006).

- Leegsma-Vogt, G., Janle, E., Ash, S. R., Venema, K., Korf, J. Utilization of in vivo ultrafiltration in biomedical research and clinical applications. Life Sciences. 73 (16), 2005-2018 (2003).

- Schneiderheinze, J. M., Hogan, B. L. Selective in vivo and in vitro sampling of proteins using miniature ultrafiltration sampling probes. Analytical Chemistry. 68 (21), 3758-3762 (1996).

- Hardt, M., Lam, D. K., Dolan, J. C., Schmidt, B. L. Surveying proteolytic processes in human cancer microenvironments by microdialysis and activity-based mass spectrometry. Proteomics Clinical Applications. 5 (11-12), 636-643 (2011).

- Xu, B. J., et al. Microdialysis combined with proteomics for protein identification in breast tumor microenvironment in vivo. Cancer Microenvironment. 4 (1), 61-71 (2010).

- Bendrik, C., Dabrosin, C. Estradiol increases IL-8 secretion of normal human breast tissue and breast cancer in vivo. The Journal of Immunology. 182 (1), 371-378 (2009).

- Ao, X., Stenken, J. A. Microdialysis sampling of cytokines. Methods. 38 (4), 331-341 (2006).

- Ho, P. C., et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell. 162 (6), 1217-1228 (2015).

- Choi, J., et al. Intraperitoneal immunotherapy for metastatic ovarian carcinoma: Resistance of intratumoral collagen to antibody penetration. Clinical Cancer Research. 12 (6), 1906-1912 (2006).

- Wiig, H., Aukland, K., Tenstad, O. Isolation of interstitial fluid from rat mammary tumors by a centrifugation method. The American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 284 (1), 416-424 (2003).

- Li, S., Wang, R., Zhang, M., Wang, L., Cheng, S. Proteomic analysis of non-small cell lung cancer tissue interstitial fluids. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 11, 173 (2013).

- Fijneman, R. J., et al. Proximal fluid proteome profiling of mouse colon tumors reveals biomarkers for early diagnosis of human colorectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 18 (9), 2613-2624 (2012).

- Teng, P. N., Hood, B. L., Sun, M., Dhir, R., Conrads, T. P. Differential proteomic analysis of renal cell carcinoma tissue interstitial fluid. Journal of Proteome Research. 10 (3), 1333-1342 (2011).

- Turtoi, A., et al. Novel comprehensive approach for accessible biomarker identification and absolute quantification from precious human tissues. Journal of Proteome Research. 10 (7), 3160-3182 (2011).

- Wagner, M., Wiig, H. Tumor Interstitial Fluid Formation, Characterization, and Clinical Implications. Frontiers in Oncology. 5, 115 (2015).

- Haslene-Hox, H., Tenstad, O., Wiig, H. Interstitial fluid-a reflection of the tumor cell microenvironment and secretome. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 1834 (11), 2336-2346 (2013).

- Hsieh, S. Y., et al. Secreted ERBB3 isoforms are serum markers for early hepatoma in patients with chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. Journal of Proteome Research. 10, 4715-4724 (2011).

- Sun, W., et al. Characterization of the liver tissue interstitial fluid (TIF) proteome indicates potential for application in liver disease biomarker discovery. Journal of Proteome Research. 9 (2), 1020-1031 (2010).

- Haslene-Hox, H., et al. Increased WD-repeat containing protein 1 in interstitial fluid from ovarian carcinomas shown by comparative proteomic analysis of malignant and healthy gynecological tissue. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 1834 (11), 2347-2359 (2013).

- Wang, T. H., et al. Stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 as a secreted biomarker for human ovarian cancer promotes cancer cell proliferation. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 9, 1873-1884 (2010).

- Gromov, P., et al. Up-regulated proteins in the fluid bathing the tumour cell microenvironment as potential serological markers for early detection of cancer of the breast. Molecular Oncology. 4 (1), 65-89 (2010).