一个简单的临界尺寸股骨缺损模型小鼠

Summary

Animal models are frequently employed to mimic serious bone injury in biomedical research. Due to their small size, establishment of stabilized bone lesions in mice are beyond the capabilities of most research groups. Herein, we describe a simple method for establishing and analyzing experimental femoral defects in mice.

Abstract

While bone has a remarkable capacity for regeneration, serious bone trauma often results in damage that does not properly heal. In fact, one tenth of all limb bone fractures fail to heal completely due to the extent of the trauma, disease, or age of the patient. Our ability to improve bone regenerative strategies is critically dependent on the ability to mimic serious bone trauma in test animals, but the generation and stabilization of large bone lesions is technically challenging. In most cases, serious long bone trauma is mimicked experimentally by establishing a defect that will not naturally heal. This is achieved by complete removal of a bone segment that is larger than 1.5 times the diameter of the bone cross-section. The bone is then stabilized with a metal implant to maintain proper orientation of the fracture edges and allow for mobility.

Due to their small size and the fragility of their long bones, establishment of such lesions in mice are beyond the capabilities of most research groups. As such, long bone defect models are confined to rats and larger animals. Nevertheless, mice afford significant research advantages in that they can be genetically modified and bred as immune-compromised strains that do not reject human cells and tissue.

Herein, we demonstrate a technique that facilitates the generation of a segmental defect in mouse femora using standard laboratory and veterinary equipment. With practice, fabrication of the fixation device and surgical implantation is feasible for the majority of trained veterinarians and animal research personnel. Using example data, we also provide methodologies for the quantitative analysis of bone healing for the model.

Introduction

据估计,一半的美国人口经历了骨折的65 1岁。对于那些患者的治疗骨折手术,500000过程涉及使用骨移植2,这个数字预计将上升与人口日趋老龄化3 。虽然骨是少数器官具有完全愈合无疤痕的能力之一,有其中过程失败3,4是实例。根据具体情况和治疗的质量,长骨骨折的2-30%失败,从而导致非工会3,5。虽然仍存在的定义,假关节,临界尺寸或不愈合骨损伤有些争论,一般是指不愈合覆盖主体6的自然寿命的伤害。为实验目的,此持续时间缩短为所需的平均大小的骨损伤完全愈合的平均时间。非工会骨骼发生病变货号危。原因,但主要的因素包括产生了极其大的差距,感染,血管差,烟草使用,或抑制osteoregenerative能力因疾病或7岁极端的创伤。即使非工会的成功治疗,它可以超过60,000美元的过程成本,这取决于损伤的类型和使用的8途径 。

在温和的情况下,自体骨移植是就业。这一战略包括从损伤部位供体部位和植入恢复骨。虽然这种方法是非常有效的,可用的供体来源的骨量是有限的,该过程涉及一个附加的外科手术,这导致持续性疼痛在许多患者9,10。另外,自体骨移植物的功效取决于患者的健康。从合成材料或加工尸体骨制作的骨代用品大量可用11-13,但他们公顷已经显著限制,包括差的宿主-细胞粘着性,减少的骨传导性,以及用于免疫排斥14的潜力。有因此,迫切需要用于骨骼再生的技术,是安全,有效和广泛使用。

我们以改善骨再生战略的能力主要取决于模仿严重骨创伤中的试验动物的能力,但对大的骨病变的产生和稳定化在技术上是有挑战性的。在大多数情况下,严重的长骨创伤是通过建立一个缺陷,即不会自然愈合实验模仿。虽然它可以与物种15而变化,这是通过完全除去一个骨片段,它是骨的横截面16的大于1.5倍的直径的实现。骨然后用金属植入物稳定,以保持骨折边缘的正确取向,并允许流动。由于它们的小尺寸和的脆弱其长骨,建立这样的病变的小鼠都超出了大多数的研究小组的功能。因此,长骨缺损模型仅限于老鼠和较大的动物。然而,小鼠得到显著研究的优点在于,它们可以被遗传修饰并饲养作为免疫妥协菌株不拒绝人类细胞和组织。

对于人体细胞为基础的应用,免疫功能低下小鼠与吸引力,因为他们在生理上良好的特点,易家的工作,成本效益,易于分析影像学和组织学。最重要的是,免疫妥协小鼠中不拒绝来自不同物种,包括人类细胞。它们的小尺寸还允许非常小的数量的细胞或实验支架在整形外科应用的卷的测试。几种鼠矫形模型已报道,得到不同程度的骨稳定17,18。这些SYSTE这导致非常高的稳定性水平,如外固定器和锁定板毫秒主要由膜内骨化愈合虽然软骨内愈合已经报道19。与此相反,那些允许一些微观和/或宏观的运动,如那些使用未固定的或部分固定髓针,一般治愈与软骨内骨化20,21的一个优势。延迟愈合或长骨的不愈合缺陷是特别难以实现在小鼠中,由于稳定化所需要的额外的水平。然而,一些方法已被报道,包括髓销与髓内钉,锁定板和外固定器22上 。这些系统一般工作良好,但鉴于其复杂的设计,他们可以在技术上具有挑战性的安装。例如,Garcia 等。23设计优雅联锁销系统,用于在小鼠中使用,但该方法包括切口在两个分开的部位s和股骨的大量修改,以容纳插针。这些程序在解剖显微镜下进行的。

在此,我们描述一个简单的股骨骨髓销钉与中央领设计成防止关闭3毫米的骨缺损,也描绘缺陷的原边。而销没有被固定到骨头本身,销直径髓腔导致足够的干扰和扩孔的精确大小,以尽量减少扭转运动( 图1)。通过仔细挑选的近交的年龄,性别和应变匹配小鼠,其结果是一个高度可再生肥厚非uniondefect 22可以很容易地进行评估放射学。另外的感兴趣的区域可以显微计算机断层摄影术(μCT) 从头骨形成和组织形态学参数的测量之后被再现地限定。引脚用现成的工具原型在我们的实验室。

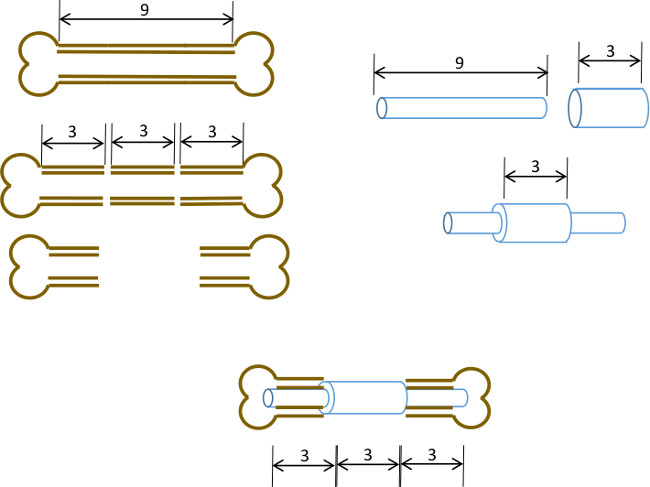

图1:实验原理节段性缺损模型的图解总结。一个9-10毫米的鼠股骨的中央3毫米段被手术切除( 左 )。 A 3毫米长,19轨距外科钢管越过9毫米长,22克的不锈钢管和固定用粘合剂在准确的中心( 右 )。所得销装配到股骨的其余的近端和远端部分的与19克衣领置换骨的3毫米段( 下面,中心 )的髓管。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

在此,我们描述一个简单的方法来产生使用标准实验室和兽医器械鼠股骨的临界尺寸的针稳定缺陷。而引脚和手术本身的装配要求的做法,它是指一个训练有素的生物医学研究的科学家或兽医的能力很好。

销被定位成髓管,无需额外的固定,使该过程在技术上更重要的是使用外固定器或互锁螺钉更复杂的方法是可行的。而在愈合的早期阶段,可能会出现一些扭转运动,这是?…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

我们这项技术的发展过程中,在谢比较医学,寺,得克萨斯州的斯科特与白医院处的工作人员和兽医,提供了宝贵的建议和帮助。这项工作是由再生医学研究所的项目经费,斯科特和怀特RGP批#90172,NIH 2P40RR017447-07和NIH R01AR066033-01(NIAMS)的部分资助。我们感谢苏珊Zeitouni博士校对书稿。

Materials

| Name of Equipment/Material* | Company | Catalog or model | Notes |

| Pin Assembly | |||

| Dremel rotary tool | Dremel | 8220 | or equivalent |

| Heavy duty cut off wheel | Dremel | 420 | |

| Surgical tubing 19G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMZ8LY | OD 1.07mm, ID 0.889mm |

| Surgical tubing 21G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMZ8YQ | OD 0.82mm, ID 0.635mm |

| Surgical tubing 22G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMYLZS | OD 0.719mm, ID 0.502mm |

| Surgical tubing 23G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FN0SY0 | OD 0.643mm, ID 0.444mm |

| Cyanoacrylate adhesive | Loctite | 1365882 | |

| Emery disc | Dremel | 413 | |

| Rubber polishing point | Dremel | 462 | |

| Felt polishing disc | Dremel | 414 | |

| Gelatin sponge | Surgifoam/Ethicon | 1974 | |

| Punch biopsy cutter | Miltex | 33-34 | |

| Surgery/post-operative | |||

| Warm pad and circulator pump | Stryker/Thermocare | TP700, TP700C, TPP722 | |

| Coverage quaternary spray | Steris | 1429-77 | |

| Bead sterilizer | Germinator/CellPoint Scentific | Germinator 500 | |

| Anesthesia system | VetEquip Inc | 901806 or 901807/901809 | |

| Isofluorane anesthetic | VETone/MWI | 501017, 502017 | |

| Surgical disinfectant | Chloraprep/CareFusion | 260449 | |

| Surgical tools | Fine Science Tools | various | recommend German made |

| Face protection | Splash Shield | 4505 | |

| Rechargable high speed drill | Fine Science Tools | 18000-17 | |

| Diamond cutting wheel | Strauss Diaiond | 361.514.080HP | |

| Absorbable sutures | Covidien | UM-213 | |

| Outer sutures | Ethicon | 668G | or equivalent |

| Vetbond | 3M | 1469SB | or equivalent |

| Hydration gel | Clear H2O | 70-01-1082 | |

| Diet gel | Clear H2O | 72-01-1062 | |

| Buprenorphine | Reckitt and Benckser | 12496-0757-01 | controlled substance |

| Mouse igloos | Bio Serv | K3328, 3570,3327 | |

| Euthanasia cocktail | Euthasol/Virbac | 710101 | controlled substance |

| Analysis | |||

| Live animal imager | Orthoscan | FD Pulse | or equivalent |

| Micro-CT unit and software | Bruker | Skyscan1174 | or equivalent |

| Sealing film/Parafilm M | VWR or Fisher | 100501-338, S37441 | |

| *Generic sources are suitable for all other items such as gause, drapes, protective clothing, animal care equipment. | |||

Referências

- Brinker, M. R., O’Connor, D. P. The incidence of fractures and dislocations referred for orthopaedic services in a capitated population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 86, 290-297 (2004).

- Cheung, C. The future of bone healing. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 22, 631-641 (2005).

- Rosemont, I. L. . United States Bone and Joint Decade: The burden of musculoskeletal diseases and musculoskeletal injuries. , (2008).

- Tzioupis, C., Giannoudis, P. V. Prevalence of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 38, S3-S9 (2007).

- Marsh, D. Concepts of fracture union, delayed union, and nonunion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. , S22-S30 (1998).

- Spicer, P. P., et al. Evaluation of bone regeneration using the rat critical size calvarial defect. Nat Protoc. 7, 1918-1929 (2012).

- Green, E., Lubahn, J. D., Evans, J. Risk factors, treatment, and outcomes associated with nonunion of the midshaft humerus fracture. J Surg Orthop Adv. 14, 64-72 (2005).

- Kanakaris, N. K., Giannoudis, P. V. The health economics of the treatment of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 38, S77-S84 (2007).

- Dimitriou, R., Mataliotakis, G. I., Angoules, A. G., Kanakaris, N. K., Giannoudis, P. V. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 42, S3-S15 (2011).

- Boer, H. H. The history of bone grafts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. , 292-298 (1988).

- Aro, H. T., Aho, A. J. Clinical use of bone allografts. Ann Med. 25, 403-412 (1993).

- Burstein, F. D. Bone substitutes. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 37, 1-4 (2000).

- Kao, S. T., Scott, D. D. A review of bone substitutes. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 19, 513-521 (2007).

- Boden, S. D. Overview of the biology of lumbar spine fusion and principles for selecting a bone graft substitute. Spine. (Phila Pa 1976). 27, S26-S31 (1976).

- Hollinger, J. O., Kleinschmidt, J. C. The critical size defect as an experimental model to test bone repair materials). J Craniofac Surg. 1, 60-68 (1990).

- Key, J. The effect of local calcium depot on osteogenesis and healing of fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Am). 16, 176-184 (1934).

- Holstein, J. H., et al. Advances in the establishment of defined mouse models for the study of fracture healing and bone regeneration). J Orthop Trauma. 23, S31-S38 (2009).

- Histing, T., et al. Small animal bone healing models: standards, tips, and pitfalls results of a consensus meeting. Bone. 49, 591-599 (2011).

- Cheung, K. M., et al. An externally fixed femoral fracture model for mice. J Orthop Res. 21, 685-690 (2003).

- Hiltunen, A., Vuorio, E., Aro, H. T. A standardized experimental fracture in the mouse tibia. J Orthop Res. 11, 305-312 (1993).

- Manigrasso, M. B., O’Connor, J. P. Characterization of a closed femur fracture model in mice. J Orthop Trauma. 18, 687-695 (2004).

- Garcia, P., et al. Rodent animal models of delayed bone healing and non-union formation: a comprehensive review. Eur Cell Mater. 26, 1-12 (2013).

- Garcia, P., et al. Development of a reliable non-union model in mice. J Surg Res. 147, 84-91 (2008).

- Flecknell, P. A. The relief of pain in laboratory animals. Lab Anim. 18, 147-160 (1984).

- . . Guidelines on the Euthanasia of Animals. , (2013).

- Neill, K. R., et al. Micro-computed tomography assessment of the progression of fracture healing in mice. Bone. 50, 1357-1367 (2012).

- Bagi, C. M., et al. The use of micro-CT to evaluate cortical bone geometry and strength in nude rats: correlation with mechanical testing, pQCT and DXA. Bone. 38, 136-144 (2006).

- Hadjiargyrou, M., et al. Transcriptional profiling of bone regeneration. Insight into the molecular complexity of wound repair. J Biol Chem. 277, 30177-30182 (2002).

- Clough, B. H., et al. Bone regeneration with osteogenically enhanced mesenchymal stem cells and their extracellular matrix proteins. J Bone Miner Res. , (2014).

- Lu, C., et al. Cellular basis for age-related changes in fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 23, 1300-1307 (2005).

- Jepsen, K. J., et al. Genetic variation in the patterns of skeletal progenitor cell differentiation and progression during endochondral bone formation affects the rate of fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 23, 1204-1216 (2008).

- Thayer, T. C., Wilson, S. B., Mathews, C. E. Use of nonobese diabetic mice to understand human type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 39, 541-561 (2010).

- Jee, W. S., Yao, W. Overview: animal models of osteopenia and osteoporosis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 1, 193-207 (2001).