聚合酶链反应和斑点-印迹杂交用于水样中 钩端螺旋体 检测

Summary

在这项研究中,设计了一种斑点印迹应用来检测水样中三个主要分支的 钩端螺旋体 。该方法允许鉴定地高辛标记探针特异性靶向的最小 DNA 量,很容易被抗地高辛抗体检测到。这种方法是用于筛选目的的有价值和令人满意的工具。

Abstract

斑点印迹是一种简单、快速、灵敏且用途广泛的技术,能够在存在载体 DNA 的情况下鉴定探针杂交特异性靶向的最小量 DNA。它基于将已知量的 DNA 转移到惰性固体支持物(例如尼龙膜)上,利用斑点印迹装置,无需电泳分离。尼龙膜具有核酸结合载量高(400 μg/cm2)、强度高、带正电荷或带中性电荷等优点。使用的探针是高度特异性的 ssDNA 片段,由 18 至 20 个碱基组成,用地高辛 (DIG) 长标记。探针将与 钩端螺旋体 DNA 结合。一旦探针与目标 DNA 杂交,它就会被抗地高辛抗体检测到,从而可以通过 X 射线胶片中显示的发射物轻松检测。带有发射的点将对应于感兴趣的 DNA 片段。该方法采用探针的非同位素标记,其半衰期可能非常长。这种标准免疫标记物的缺点是灵敏度低于同位素探针。然而,通过偶联聚合酶链反应 (PCR) 和斑点印迹测定可以缓解这种情况。这种方法可以富集靶序列并进行检测。此外,与知名标准品的系列稀释液相比,它可以用作定量应用。本文介绍了一种斑点印迹法检测水样中三个主要分支钩 端螺旋体 的应用方法。一旦通过离心浓缩了大量的水,就可以将这种方法应用于大量的水,以提供钩端螺旋体DNA存在的证据。对于一般筛查目的,这是一种有价值且令人满意的工具,可用于水中可能存在的其他不可培养细菌,从而增强对生态系统的理解。

Introduction

人类钩端螺旋体病主要源于环境来源1,2。钩端螺旋体存在于湖泊、河流和溪流中,是钩端螺旋体病在野生动物以及最终可能接触这些水体的家畜和生产动物中传播的一个指标1,3,4。此外,钩端螺旋体已在非自然资源中被发现,包括污水、死水和自来水 5,6。

钩端螺旋体是一种全球分布的细菌7,8,环境在其保存和传播中的作用已得到充分认识。钩端螺旋体可以在可变 pH 值和矿物质9 下的饮用水中生存,并且可以在自然水体中生存1。它也可以在蒸馏水中长期存活10,在恒定的 pH 值 (7.8) 下,它可以存活长达 152 天11。此外,钩端螺旋体可能在细菌联合体中相互作用,以在恶劣的条件下生存12,13。它可能是淡水中生物膜的一部分,含有偶氮螺菌和鞘氨醇单胞菌,甚至能够生长和承受超过 49 °C的温度 14,15。它还可以在涝渍的土壤中繁殖,并保持活力长达 379 天16,保持其引起疾病的能力长达一年17,18。然而,人们对水体内的生态学及其在水体中的分布知之甚少。

自发现以来,钩端螺旋体属的研究基于血清学测试。直到本世纪,分子技术才在这种螺旋体的研究中变得更加普遍。点印迹法很少用于使用 (1) 基于 16S rRNA 和简单序列重复序列 (ISSR) 19,20 的同位素探针进行鉴定,(2) 作为应用于尿液的人钩端螺旋体病的基于纳米金的免疫测定21,或 (3) 作为基于抗体的牛尿液样本测定22.该技术被废弃了,因为它最初是基于同位素探针的。然而,它是一种众所周知的技术,与PCR相结合,可以产生更好的结果,并且由于使用了非同位素探针,它被认为是安全的。PCR在钩端螺旋体DNA的富集中起着至关重要的作用,它通过扩增可能在样品中微量发现的特定DNA片段。在每个PCR循环中,反应中靶向DNA片段的量增加一倍。在反应结束时,扩增子已乘以超过一百万倍23。通过PCR扩增的产物在琼脂糖电泳中通常不可见,通过在斑点印迹24,25,26中使用DIG标记的探针进行特异性杂交而变得可见。

斑点印迹技术简单、稳健,适用于大量样品,使资源有限的实验室能够使用。它已被用于各种细菌研究,包括 (1) 口腔细菌27,(2) 其他样品类型,如食物和粪便28,以及 (3) 不可培养细菌的鉴定29,通常与其他分子技术一致。斑点印迹技术的优点包括:(1)该膜具有高结合载量,能够结合超过200μg/cm 2 的核酸和高达400μg/cm2的核酸;(2) 斑点印迹结果无需特殊设备即可目视解读,(3) 它们可以在室温 (RT) 下方便地储存多年。

钩端螺旋体属已分为致病性、中间性和腐生分支30,31。这些分支之间的区别可以基于特定的基因来实现,例如 lipL41、lipL32 和 16S rRNA。LipL32 存在于致病分支中,在各种血清学和分子工具中表现出高敏感性,而在腐生菌属21 中不存在。管家基因 lipL41 以其稳定的表达而闻名,并在分子技术中使用32,而 16S rRNA 基因用于分类。

一旦通过离心浓缩了大量的水,这种方法就可以应用于水。它允许评估水体内的各个点和深度,以检测钩端螺旋体DNA的存在及其所属的分支。该工具对于生态学和一般筛查目的都很有价值,也可用于检测水中可能存在的其他不可培养细菌。

此外,PCR和斑点印迹检测对于各种实验室来说在技术和经济上都是负担得起的,即使是那些缺乏复杂或昂贵设备的实验室也是如此。本研究旨在应用基于地高辛的斑点印迹法鉴定从自然水体收集的水样中的三个 钩端螺旋体 分支。

菌株

本研究纳入 12 个 钩端螺旋体 血清型(Autumnalis、Bataviae、Bratislava、Canicola、Celledoni、Grippothyphosa、Hardjoprajitno、Icterohaemorrhagiae、Pomona、Pyrogenes、Tarassovi 和 Wolffi)。这些血清型是墨西哥国立自治大学兽医和动物技术学院微生物学和免疫学系收集的一部分,它们目前用于微凝集试验 (MAT)。

所有 钩端螺旋体 血清型均在 EMJH 中培养,并使用商业 DNA 提取试剂盒提取其 DNA(参见 材料表)。将 12 个血清型的基因组 DNA 混合物用作 钩端螺旋体 致病分支的阳性对照。作为 钩端螺旋体 中间分支的阳性对照,纳入了 Fainei钩端螺旋 体血清型Hurstbridge菌株BUT6的基因组DNA,作为钩 端螺旋 体腐生菌分支的阳性对照,还包括 双曲钩端螺旋体 血清型Patoc菌株Patoc I的基因组DNA。

阴性对照包括空质粒、来自非亲缘细菌(解脲支原体、金黄色葡萄球菌、流产布鲁氏菌、鼠伤寒沙门氏菌、博伊氏志贺氏菌、肺炎克雷伯菌、鲍曼不动杆菌 和 大肠杆菌)的 DNA 和 PCR 级水,用作非模板对照。

水样

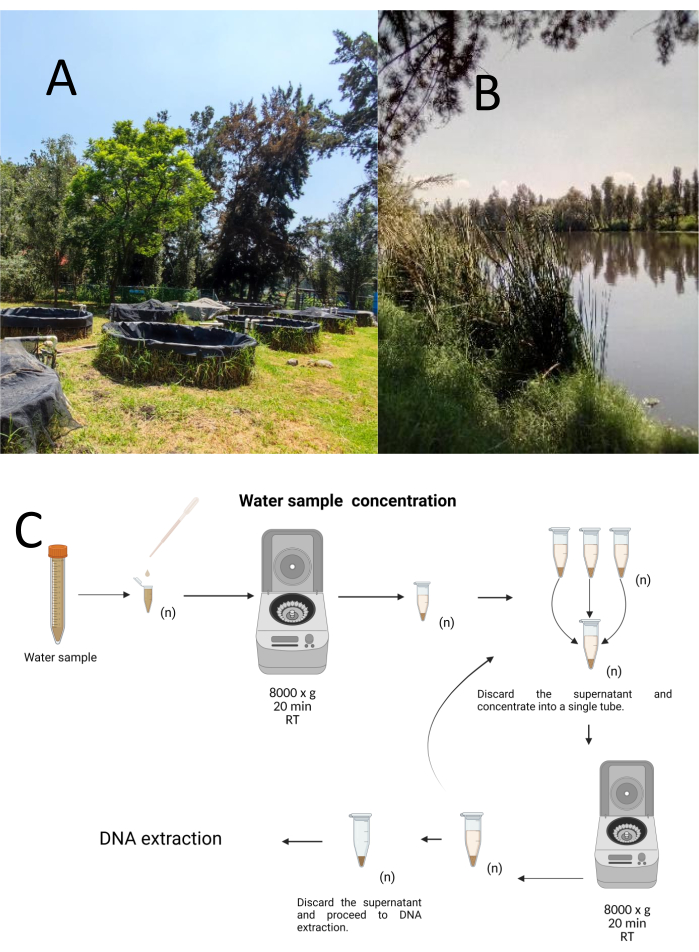

使用分层随机抽样方法从Cuemanco生物和水产养殖研究中心(CIBAC)(19° 16′ 54“ N 99° 6′ 11” W)收集了12个试验抓取样本。这些样品是在三个深度获得的:浅表、10 和 30 厘米(图 1A、B)。取水程序没有影响任何濒危或受保护的物种。每个样品都收集在无菌 15 mL 微量离心管中。为了收集样品,将每个试管轻轻浸入水中,在选定的深度填充,然后密封。将样品保持在22°C,并迅速运送到实验室进行处理。

通过在无菌 1.5 mL 微量离心管中在室温下以 8000 x g 离心 20 分钟浓缩每个样品。重复此步骤,直到所有样品浓缩到一个试管中,然后用于DNA提取(图1C)。

图1:通过离心浓缩水样。 (A) 水样池塘,以及 (B) 自然溪流。(C) 基于离心法的水样处理,根据需要重复多次(n)。 请点击这里查看此图的较大版本.

DNA提取

根据制造商的说明,使用商业基因组 DNA 试剂盒分离总 DNA(参见 材料表)。将DNA提取物在20μL洗脱缓冲液中洗脱,通过UV分光光度计在260-280nm处测定DNA浓度,并在4°C下储存直至使用。

PCR扩增

PCR 靶标是 16个 S rRNA、lipL41 和 lipL32 基因,它们识别钩端螺旋体属的 DNA,并允许区分三个分支:致病性、腐生性和中间体。引物和探针的设计均基于 Ahmed 等人、Azali 等人、Bourhy 等人、Weiss 等人和 Branger 等人之前的工作33,34,35,36,37。每种探针、引物和扩增片段的序列见表1,其与参考序列的比对见补充文件1、补充文件2、补充文件3、补充文件4和补充文件5。PCR试剂和热循环条件在协议部分进行了描述。

通过在TAE(40mM Tris碱,20mM乙酸和1mM EDTA;pH 8.3)中,在60 V下电泳分离45 min,使用乙锭溴化物检测45分钟来观察扩增产物,如补充图1所示。根据致病性钩端螺旋体的基因组大小(4, 691, 184 bp)38,腐生钩端螺旋体的基因组大小(3, 956, 088 bp)39,从每个血清型获得的基因组DNA的浓度范围为6 x 106至1 x 104个基因组当量拷贝(GEq), Fainei serovar Hurstbridge菌株BUT6的基因组大小(4,267,324 bp),种质数为AKWZ00000000.2。

在每个实验中,使用来自每个致病性血清型的 DNA 评估探针的灵敏度,即 L. biflexa 血清型 Patoc 菌株 Patoc I 和 L. fainei 血清型 Hurstbridge 菌株 BUT6。为了评估PCR和斑点印迹杂交测定的特异性,包括来自非亲缘细菌的DNA。

表1:PCR引物和探针,用于扩增产物,用于鉴定钩端螺旋体的致病性、腐生菌和中间分支。请按此下载此表格。

斑点印迹杂交试验

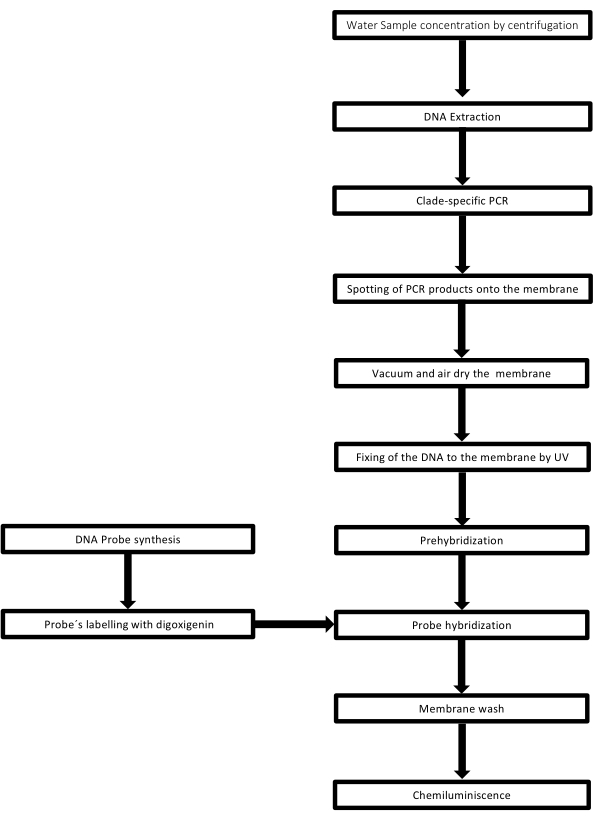

该技术被称为点印迹,因为放置 DNA 样品的孔具有点状,当它们被吸入通过真空吸力固定到位时,它们会获得这种形状。该技术由 Kafatos 等人开发[40]。该技术允许对每个PCR阳性样品中的 钩端螺旋体 进行半定量。该方案包括在室温下用NaOH 0.4M变性,将具有30ng至0.05ng的 钩端螺旋 体DNA样品,对应于6×106 至1×104 钩端螺旋体,用96孔斑点印迹装置吸迹到尼龙膜上。固定后,DNA 通过暴露于 120 mJ 紫外线与膜结合。每个 DNA 探针通过 3′ 端的末端转移酶催化步骤与地高辛-11 dUTP 偶联(地高辛是从 洋地黄获得的植物类固醇,用作报告基因41)。在将标记的 DNA 探针 (50 pmol) 在特定温度下严格杂交到靶 DNA 上后,通过化学发光反应与抗地高辛碱性磷酸酶抗体与其底物 CSPD 共价偶联来观察 DNA 杂交体。通过暴露于X射线胶片来捕获发光(图2)。

图 2:PCR-dot-blot 检测的程序步骤。 请点击这里查看此图的较大版本.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

斑点印迹技术的关键步骤包括:(1)DNA固定化,(2)用非同源DNA阻断膜上的游离结合位点,(3)退火条件下探针和靶片段之间的互补性,(4)去除未杂交的探针,以及(5)检测报告分子41。

PCR-Dot-blot具有一定的局限性,例如该技术不提供有关杂交片段37大小的信息,它需要在与第二个或第三个探针重新杂交之前对单个膜进行去杂交,并?…

Declarações

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

我们感谢墨西哥国立自治大学兽医和动物技术学院微生物学和免疫学系的钩端螺旋体收藏。我们感谢对参考钩端螺旋体菌株的慷慨捐赠;Lebtospira fainei 血清型 Hurstbridge 菌株 BUT6 和 Leptospira biflexa 血清型 Patoc 菌株 Patoc I 给 Alejandro de la Peña Moctezuma 博士。我们感谢CIBAC协调员José Antonio Ocampo Cervantes博士和工作人员的后勤支持。EDT属于Metropolitan Autonomous University-Campus Cuajimalpa本科生的终端项目计划。我们承认用于创建图 1 和图 3 至 9 的 Biorender.com 软件。

Materials

| REAGENTS | |||

| Purelink DNA extraction kit | Invitrogen | K182002 | |

| Gotaq Flexi DNA Polimerase (End-Point PCR Taq polymerase kit) | Promega | M3001 | |

| Whatman filter paper, grade 1, | Merk | WHA1001325 | |

| Nylon Membranes, positively charged Roll 30cm x 3 m | Roche | 11417240001 | |

| Anti-Digoxigenin-AP, Fab fragments Sheep Polyclonal Primary-antibody | Roche | 11093274910 | |

| Medium Base EMJH | Difco | S1368JAA | |

| Leptospira Enrichment EMJH | Difco | BD 279510 | |

| Blocking Reagent | Roche | 11096176001 | |

| CSPD ready to use Disodium 3-(4-methoxyspiro {1,2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′-chloro) tricyclo [3.3.1.13,7] decan}8-4-yl) phenyl phosphate | Merk | 11755633001 | |

| Deoxyribonucleic acid from herring sperm | Sigma Aldrich | D3159 | |

| Developer Carestream | Carestream Health Inc | GBX5158621 | |

| Digoxigenin-11-ddUTP | Roche | 11363905910 | |

| EDTA, Disodium Salt (Dihydrate) | Promega | H5032 | |

| Ficoll 400 | Sigma Aldrich | F8016 | |

| Fixer Carestream | Carestream Health Inc | GBX 5158605 | |

| Lauryl sulfate Sodium Salt (Sodium dodecyl sulfate; SDS) C12H2504SNa | Sigma Aldrich | L5750 | |

| N- Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt CH3(CH2)10CON(CH3) CH2COONa | Sigma Aldrich | L-9150 | It is an anionic surfactant |

| Polivinylpyrrolidone (PVP-40) | Sigma Aldrich | PVP40 | |

| Polyethylene glycol Sorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20) | Sigma Aldrich | 9005-64-5 | |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Sigma Aldrich | 7647-14-5 | |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) | Sigma Aldrich | 151-21-3 | |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | Sigma Aldrich | 1310-73-2 | |

| Sodium phosphate dibasic (NaH2PO4) | Sigma-Aldrich | 7558-79-4 | |

| Terminal transferase, recombinant | Roche | 3289869103 | |

| Tris hydrochloride (Tris HCl) | Sigma-Aldrich | 1185-53-1 | |

| SSPE 20X | Sigma-Aldrich | S2015-1L | It can be Home-made following Supplementary File 6 |

| Primers | Sigma-Aldrich | On demand | Follow table 1 |

| Probes | Sigma-Aldrich | On demand | Follow table 1 |

| Equipment | |||

| Nanodrop™ One Spectrophotometer | Thermo-Scientific | ND-ONE-W | |

| Refrigerated microcentrifuge Sigma 1-14K, suitable for centrifugation of 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes at 14,000 rpm | Sigma-Aldrich | 1-14K | |

| Disinfected adjustable pipettes, range 2-20 µl, 20-200 µl | Gilson | SKU:F167360 | |

| Disposable 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes (autoclaved) | Axygen | MCT-150-SP | |

| Disposable 600 µl microcentrifuge tubes (autoclaved) | Axygen | 3208 | |

| Disposable Pipette tips 1-10 µl | Axygen | T-300 | |

| Disposable Pipette tips 1-200 µl | Axygen | TR-222-Y | |

| Dot-Blot apparatus Bio-Dot | BIORAD | 1706545 | |

| Portable Hergom Suction | Hergom | 7E-A | |

| Scientific Light Box (Visible-light PH90-115V) | Hoefer | PH90-115V | |

| UV Crosslinker | Hoefer | UVC-500 | |

| Thermo Hybaid PCR Express Thermocycler | Hybaid | HBPX110 | |

| Radiographic cassette with IP Plate14 X 17 | Fuji |

Referências

- Bierque, E., Thibeaux, R., Girault, D., Soupé-Gilbert, M. E., Goarant, C. A systematic review of Leptospira in water and soil environments. PLOS One. 15 (1), e0227055 (2020).

- Haake, D. A., Levett, P. N. Leptospirosis in humans. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 387, 65-97 (2015).

- Tripathy, D. N., Hanson, L. E. Leptospires from water sources at Dixon Springs Agricultural Center. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 9 (3), 209-212 (1973).

- Smith, D. J., Self, H. R. Observations on the survival of Leptospira australis A in soil and water. The Journal of Hygiene. 53 (4), 436-444 (1955).

- Karpagam, K. B., Ganesh, B. Leptospirosis: a neglected tropical zoonotic infection of public health importance-an updated review. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases: Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 39 (5), 835-846 (2020).

- Casanovas-Massana, A., et al. Spatial and temporal dynamics of pathogenic Leptospira in surface waters from the urban slum environment. Water Research. 130, 176-184 (2018).

- Costa, F., et al. Global morbidity and mortality of Leptospirosis: A systematic review. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (9), e0003898 (2015).

- Mwachui, M. A., Crump, L., Hartskeerl, R., Zinsstag, J., Hattendorf, J. Environmental and behavioural determinants of Leptospirosis transmission: A systematic review. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (9), e0003843 (2015).

- Andre-Fontaine, G., Aviat, F., Thorin, C. Waterborne Leptospirosis: Survival and preservation of the virulence of pathogenic Leptospira spp. in fresh water. Current Microbiology. 71 (1), 136-142 (2015).

- Trueba, G., Zapata, S., Madrid, K., Cullen, P., Haake, D. Cell aggregation: A mechanism of pathogenic Leptospira to survive in freshwater. International Microbiology: the Official Journal of the Spanish Society for Microbiology. 7 (1), 35-40 (2004).

- Smith, C. E., Turner, L. H. The effect of pH on the survival of leptospires in water. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 24 (1), 35-43 (1961).

- Barragan, V. A., et al. Interactions of Leptospira with environmental bacteria from surface water. Current Microbiology. 62 (6), 1802-1806 (2011).

- Abdoelrachman, R. Comparative investigations into the influence of the presence of bacteria on the life of pathogenic and apathogenic leptospirae. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 13 (1), 21-32 (1947).

- Singh, R., et al. Microbial diversity of biofilms in dental unit water systems. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (6), 3412-3420 (2003).

- Kumar, K. V., Lall, C., Raj, R. V., Vedhagiri, K., Vijayachari, P. Coexistence and survival of pathogenic leptospires by formation of biofilm with Azospirillum. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 91 (6), 051 (2015).

- Yanagihara, Y., et al. Leptospira Is an environmental bacterium that grows in waterlogged soil. Microbiology Spectrum. 10 (2), 0215721 (2022).

- Gillespie, R. W., Ryno, J. Epidemiology of leptospirosis. American Journal of Public Health and Nation’s Health. 53 (6), 950-955 (1963).

- Bierque, E., et al. Leptospira interrogans retains direct virulence after long starvation in water. Current Microbiology. 77 (10), 3035-3043 (2020).

- Zhang, Y., Dai, B. Marking and detection of DNA of leptospires in the dot-blot and situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled probes. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences. 23 (4), 353-435 (1992).

- Mérien, F., Amouriaux, P., Perolat, P., Baranton, G., Saint Girons, I. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of Leptospira spp. in clinical samples. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 30 (9), 2219-2224 (1992).

- Veerapandian, R., et al. Silver enhanced nano-gold dot-blot immunoassay for leptospirosis. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 156, 20-22 (2019).

- Junpen, S., et al. Evaluation of a monoclonal antibody-based dot-blot ELISA for detection of Leptospira spp in bovine urine samples. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 66 (5), 762-766 (2005).

- Ishmael, F. T., Stellato, C. Principles and applications of polymerase chain reaction: basic science for the practicing physician. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology: Official Publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 101 (4), 437-443 (2008).

- Boerner, B., Weigelt, W., Buhk, H. J., Castrucci, G., Ludwig, H. A sensitive and specific PCR/Southern blot assay for detection of bovine herpesvirus 4 in calves infected experimentally. Journal of Virological Methods. 83 (1-2), 169-180 (1999).

- Curry, E., Pratt, S. L., Kelley, D. E., Lapin, D. R., Gibbons, J. R. Use of a Combined duplex PCR/Dot-blot assay for more sensitive genetic characterization. Biochemistry Insights. 1, 35-39 (2008).

- Pilatti, M. M., Ferreira, S. d. e. A., de Melo, M. N., de Andrade, A. S. Comparison of PCR methods for diagnosis of canine visceral leishmaniasis in conjunctival swab samples. Research in Veterinary Science. 87 (2), 255-257 (2009).

- Conrads, G., et al. PCR reaction and dot-blot hybridization to monitor the distribution of oral pathogens within plaque samples of periodontally healthy individuals. Journal of Periodontology. 67 (10), 994-1003 (1996).

- Langa, S., et al. Differentiation of Enterococcus faecium from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus strains by PCR and dot-blot hybridisation. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 88 (2-3), 197-200 (2003).

- Francesca, C., Lucilla, I., Marco, F., Giuseppe, C., Marisa, M. Identification of the unculturable bacteria Candidatus arthromitus in the intestinal content of trouts using dot-blot and Southern blot techniques. Veterinary Microbiology. 156 (3-4), 389-394 (2012).

- Arent, Z., Pardyak, L., Dubniewicz, K., Plachno, B. J., Kotula-Balak, M. Leptospira taxonomy: then and now. Medycyna Weterynaryjna. 78 (10), 489-496 (2022).

- Thibeaux, R., et al. Biodiversity of environmental Leptospira: Improving identification and revisiting the diagnosis. Frontiers in Microbiology. 9, 816 (2018).

- Carrillo-Casas, E. M., Hernández-Castro, R., Suárez-Güemes, F., de la Peña-Moctezuma, A. Selection of the internal control gene for real-time quantitative RT-PCR assays in temperature treated Leptospira. Current Microbiology. 56 (6), 539-546 (2008).

- Azali, M. A., Yean Yean, C., Harun, A., Aminuddin Baki A, N. N., Ismail, N. Molecular characterization of Leptospira spp. in environmental samples from North-Eastern Malaysia revealed a pathogenic strain, Leptospira alstonii. Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2016, 2060241 (2016).

- Ahmed, N., et al. Multilocus sequence typing method for identification and genotypic classification of pathogenic Leptospira species. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 5, 28 (2006).

- Bourhy, P., Collet, L., Brisse, S., Picardeau, M. Leptospira mayottensis sp. nov., a pathogenic species of the genus Leptospira isolated from humans. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 64, 4061-4067 (2014).

- Weiss, S., et al. An extended Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) scheme for rapid direct typing of Leptospira from clinical samples. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (9), e0004996 (2016).

- Branger, C., et al. Polymerase chain reaction assay specific for pathogenic Leptospira based on the gene hap1 encoding the hemolysis-associated protein-1. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 243 (2), 437-445 (2005).

- Ren, S. X., et al. Unique physiological and pathogenic features of Leptospira interrogans revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 422 (6934), 888-893 (2003).

- Picardeau, M., et al. Genome sequence of the saprophyte Leptospira biflexa provides insights into the evolution of Leptospira and the pathogenesis of leptospirosis. PLOS One. 3 (2), e1607 (2008).

- Kafatos, F. C., Jones, C. W., Efstratiadis, A. Determination of nucleic acid sequence homologies and relative concentrations by a dot hybridization procedure. Nucleic Acids Research. 7 (6), 1541-1552 (1979).

- Bhat, A. I., Rao, G. P. Dot-blot hybridization technique. Characterization of Plant Viruses. , 303-321 (2020).

- Yadav, J. P., Batra, K., Singh, Y., Singh, M. Comparative evaluation of indirect-ELISA and Dot-blot assay for serodetection of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae antibodies in poultry. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 189, 106317 (2021).

- Malinen, E., Kassinen, A., Rinttilä, T., Palva, A. Comparison of real-time PCR with SYBR Green I or 5′-nuclease assays and dot-blot hybridization with rDNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes in quantification of selected faecal bacteria. Microbiology. 149, 269-277 (2003).

- Wyss, C., et al. Treponema lecithinolyticum sp. nov., a small saccharolytic spirochaete with phospholipase A and C activities associated with periodontal diseases. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 49, 1329-1339 (1999).

- Shah, J. S., I, D. C., Ward, S., Harris, N. S., Ramasamy, R. Development of a sensitive PCR-dot-blot assay to supplement serological tests for diagnosing Lyme disease. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases: Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 37 (4), 701-709 (2018).

- Niu, C., Wang, S., Lu, C. Development and evaluation of a dot-blot assay for rapid determination of invasion-associated gene ibeA directly in fresh bacteria cultures of E. coli. Folia microbiologica. 57 (6), 557-561 (2012).

- Wetherall, B. L., McDonald, P. J., Johnson, A. M. Detection of Campylobacter pylori DNA by hybridization with non-radioactive probes in comparison with a 32P-labeled probe. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 26 (4), 257-263 (1988).

- Kolk, A. H., et al. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples by using polymerase chain reaction and a nonradioactive detection system. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 30 (10), 2567-2575 (1992).

- Scherer, L. C., et al. PCR colorimetric dot-blot assay and clinical pretest probability for diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in smear-negative patients. BMC Public Health. 7, 356 (2007).

- Armbruster, D. A., Pry, T. Limit of blank, limit of detection and limit of quantitation. The Clinical Biochemist Reviews. 29, S49-S52 (2008).

- Zhang, Y., Dai, B. Detection of Leptospira by dot-blot hybridization with photobiotin- and 32P-labeled DNA. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi like daxue xuebao. 23 (2), 130-132 (1992).

- Terpstra, W. J., Schoone, G. J., ter Schegget, J. Detection of leptospiral DNA by nucleic acid hybridization with 32P- and biotin-labeled probes. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 22 (1), 23-28 (1986).

- Shukla, J., Tuteja, U., Batra, H. V. DNA probes for identification of leptospires and disease diagnosis. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 35 (2), 346-352 (2004).

- Jiang, N., Jin, B., Dai, B., Zhang, Y. Identification of pathogenic and nonpathogenic leptospires by recombinant probes. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi like daxue xuebao. 26 (1), 1-5 (1995).

- Fach, P., Trap, D., Guillou, J. P. Biotinylated probes to detect Leptospira interrogans on dot-blot hybridization or by in situ hybridization. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 12 (5), 171-176 (1991).

- Huang, N., Dai, B. Assay of genomic DNA homology among strains of different virulent leptospira by DNA hybridization. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi like daxue xuebao. 23 (2), 122-125 (1992).

- Dong, X., Dai, B., Chai, J. Homology study of leptospires by molecular hybridization. Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi like daxue xuebao. 23 (1), 1-4 (1992).

- Komminoth, P. Digoxigenin as an alternative probe labeling for in situ hybridization. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology: The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, part B. 1 (2), 142-150 (1992).

- Saengjaruk, P., et al. Diagnosis of human leptospirosis by monoclonal antibody-based antigen detection in urine. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (2), 480-489 (2002).

- Okuda, M., et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of canine Leptospira antibodies using recombinant OmpL1 protein. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 67 (3), 249-254 (2005).

- Suwimonteerabutr, J., et al. Evaluation of a monoclonal antibody-based dot-blot ELISA for detection of Leptospira spp in bovine urine samples. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 66 (5), 762-766 (2005).

- Kanagavel, M., et al. Peptide-specific monoclonal antibodies of Leptospiral LigA for acute diagnosis of leptospirosis. Scientific reports. 7 (1), 3250 (2017).

- Levett, P. N. Leptospirosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 14 (2), 296-326 (2001).

- Monahan, A. M., Callanan, J. J., Nally, J. E. Proteomic analysis of Leptospira interrogans shed in urine of chronically infected hosts. Infection and Immunity. 76 (11), 4952-4958 (2008).

- Rojas, P., et al. Detection and quantification of leptospires in urine of dogs: a maintenance host for the zoonotic disease leptospirosis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases: Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 29 (10), 1305-1309 (2010).