שלושה הליכים מעבדה לשם הערכת ביטויים שונים של אימפולסיביות אצל חולדות

Summary

אנו מציגים שלושה פרוטוקולים של להעריך צורות שונות של אימפולסיביות ב עכברים ויונקים קטנים אחרים. שגרות בחירה intertemporal להעריך נטייה הנחה את הערך של תוצאות מושהית. חיזוק דיפרנציאלית של שיעור נמוך ואפליה תכונה-שלילי להעריך קיבולת עיכוב תגובה עם או בלי עונש על תגובות בלתי הולם, בהתאמה.

Abstract

המאמר הנוכחי מספק מדריך הולכה וניתוח של שלושה פרוטוקולים מבוססי מיזוג להערכת אימפולסיביות אצל חולדות. אימפולסיביות הוא מושג בעל משמעות כי היא מזוהה עם התנאים פסיכיאטרי אצל בני אדם ועם התנהגות maladaptive בבעלי חיים שאינם בני אדם. הוא האמין כי אימפולסיביות מורכבת של גורמים נפרדים. ישנם פרוטוקולים מעבדה המציאו כדי להעריך את כל הגורמים הללו באמצעות ציוד אוטומטי סטנדרטית. עיכוב היוון מזוהה עם היכולת כדי להיות מונע על ידי תוצאות מושהית. גורם זה מוערך דרך הבחירה intertemporal פרוטוקולים, אשר מציגים את הפרט עם מצב הבחירה מעורבים פרס מיידי ו פרס גדול אך מושהית. תגובת עיכוב קשב מזוהה עם היכולת לעכב את התגובות prepotent. חיזוק דיפרנציאלית של שיעור נמוך (DLR) ופרוטוקולים אפליה תכונה-שלילי להעריך את גורם גרעון עיכוב התגובה של אימפולסיביות. לשעבר כופה מצב אדם בעל מוטיבציה שבו רוב לחכות תקופת מינימום זמן לתגובה להיות מתוגמלים על כך. האחרון מעריך את היכולת של אנשים להימנע ממזון המבקשים תגובות כאשר אות על העדר מזון מוצג. המטרה של פרוטוקולים אלה היא לבנות מדד אובייקטיבי כמותי של אימפולסיביות, המגישה לערוך השוואות בין-המינים, מתן אפשרות המחקר translational. היתרונות של פרוטוקולים מסוימים אלה כוללים שלהם יישום, הנובעת מכך כמות קטנה יחסית של הציוד הדרוש ואת האופי האוטומטי של פרוטוקולים אלה הקמה נוחה.

Introduction

יכול להיות ממשיגים אותן אימפולסיביות כממד התנהגותיים הקשורים עם תוצאות maladaptive1. למרות השימוש הנרחב של מונח זה, יש הסכמה כללית אוניברסלי על הגדרתו המדויקת. למעשה, מספר סופרים הגדרת אימפולסיביות על ידי מתן דוגמאות בהתנהגויות אימפולסיביות או ההשלכות שלהם, ולא בהתוויית היבטים ייחודיים חלים על התופעה. למשל, אימפולסיביות ההנחה היא לערב את חוסר יכולת לחכות, לתכנן, לעכב את התנהגויות prepotent, או של חוסר רגישות תוצאות מושהית2, זה נחשב פגיעות הליבה להתנהגות ממכר3. בארי ועל רובינס4 שאפיינו אימפולסיביות כמו המופע שיתוף של דחפים חזקים, להיות מופעלות על ידי משתני והשלילית ומצבית ותהליכים המעכבת לא מתפקדת. הגדרה שונה סופק על ידי דאלי ועל רובינס, שהצהיר כי אימפולסיביות יכולות להיחשב נטייה הפעולות מהירה, לעתים קרובות מוקדם מדי, ללא תובנה המתאים5. ובכל זאת, הגדרה אחרת של אימפולסיביות, המוצע על ידי סוסה, דוס סנטוס6, נטייה התנהגות שחורגת אורגניזם של הגדלת תגמולים זמין עקב דרך השליטה הנרכש על האורגניזם מגיבה על ידי גירויים דרך אגב קשור התגמולים האלה.

עקב התהליכים התנהגותיים הקשורים אימפולסיביות, המצע neurophysiological שלה כרוכה מבנים במשותף עם אלה של התנהגות מוטיבציה, קבלת החלטות, פרס מחשיבים. זה נתמך על ידי מחקרים המראים כי מבנים של השביל cortico-striatal (למשל, גרעין האקומבנס [NAc] קליפת המוח הקדם חזיתית [PFC], האמיגדלה, putamen המזונבת [CPU]), וכן את מערכת עצבי monoaminergic עולה, להשתתף בביטוי של ההתנהגות האימפולסיבית7. אולם, המצע עצבית של אימפולסיביות הוא יותר מורכב מזה. למרות NAc, טוראי ראשון מעורבים בהתנהגות אימפולסיבית, מבנים אלה הן חלק ממערכת מורכבת יותר, גם הם הולחן על ידי substructures בעלי פונקציות שונות (עבור מפורט יותר תיעוד, ראה דאלי ועל רובינס5).

בין המחלוקות על הטבע ועל המצע הביולוגי שלה, ממד התנהגותי זה ידוע להשתנות על פני אנשים, ובמקרה זה יכול להיחשב תכונה, בתוך יחידים, ובמקרה זה יכול להיחשב המדינה8. אימפולסיביות זמן הוכר תכונה של כמה מחלות פסיכיאטריות, כמו הפרעת תשומת לב-קשב/היפראקטיביות (ADHD), התמכרות, מאניק פרקים9. נראה שיש קונצנזוס גבוה אימפולסיביות מורכב על ידי מספר גורמים dissociable, לרבות נכונות לחכות (קרי, לעכב היוון), חוסר היכולת להימנע prepotent תגובות (קרי, מעכבות קשב), קושי להתרכז הרלוונטיים מידע (קרי, חוסר תשומת לב), נטייה להתעניין במצבים מסוכנים (קרי, תחושה המבקשים)5,10,11. כל הגורמים הללו יכול להיות מוערך באמצעות פעילויות התנהגותיות מיוחד, אשר בדרך כלל מוקצים לשתי קטגוריות רחבות: עיכוב הבחירה והתגובה (אלה שיש להם תוויות שונות בין כל אחד מהם מיונים םירצוי). כמה תכונות חשובות של משימות התנהגותיים כגון הם כי הם יכול להיות מיושם בכל מיני בעלי חיים מספר2 כי הם יאפשרו לימוד אימפולסיביות בתנאי מעבדה מבוקרת.

מידול ממד התנהגותי עם חיות אנושיות מעבדה יש מספר יתרונות כולל אפשרות מדידה מסוים, להניע התנהגות נטיות, ומאפשר לחוקרים לצמצם במידה רבה את המשתנים מבלבלים, (למשל, זיהום על ידי החיים בעבר אירועים4) ואיך ליישם מניפולציות ניסיוני כגון ניהול תרופתי כרוני, ביצוע העצבים נגעים, או שינויים גנטיים. רוב פרוטוקולים אלה יש גירסאות אנלוגי על בני אדם, אשר עושים השוואות קל5. חשוב, באמצעות מקבילים של פרוטוקולים אלה מעבדה אצל בני אדם הוא יעיל לסייע באבחון של מחלות פסיכיאטריות, כמו הפרעת קשב וריכוז (במיוחד כאשר פרוטוקול אחד או יותר הוא יישומית12).

כמו כל מדידה פסיכולוגיים אחרים, פרוטוקולי מעבדה להערכת אימפולסיביות חייב לציית קריטריון מסוים על מנת להשגת המטרה לספק תובנה תופעה שנבחנה. כדי להיחשב מודל המתאים של ההתנהגות האימפולסיבית מעבדה פרוטוקול צריך להיות אמין, והינם בעלי (לפחות במידה מסויימת) הפנים, לבנות, ו/או תוקף ניבוי13. אמינות היתה לרמז כי אפקט בעת המדידה לשכפל אם מניפולציה מתבצעת פעמיים או יותר, או כי המדידה היא עקבית לאורך זמן או על פני מצבים שונים14,15. התכונה לשעבר יהיה שימושי במיוחד ללימודים ניסיוני, בעוד שהשני יהיה כך מחקרים correlational14. הפנים תוקף מתייחס למידת שבו מה נמדד דומה התופעה אמורה להיות המודל, כדי להיות, לדוגמה, מושפע המשתנים באותו. תוקף ניבוי מתייחס ליכולת של מדד תחזית ביצועים עתידי בפרוטוקולים, שמטרתם למדוד אותו או מבנה קשורים. לבסוף, לבנות תוקף מתייחס אם הפרוטוקול מתרבה התנהגות קול באופן תיאורטי לגבי התהליך או התהליכים ההנחה תהיה מעורב תופעה שנבחנה. עם זאת, למרות שאלה הן תכונות רצוי מאוד, אחד צריך להיות זהיר בעת וקבע כי פרוטוקול הוא תקף אך ורק על סמך קריטריונים אלה16.

ישנם מספר פרוטוקולים למדוד אימפולסיביות בהגדרות מעבדה. עם זאת, המאמר הנוכחי מציג רק שלוש שיטות כאלה: intertemporal ברירה, חיזוק דיפרנציאלית של שיעור נמוך ואפליה תכונה-שלילי. הליכים intertemporal במטרה להעריך את עיכוב היוון (קרי, את הקושי של תוצאות מתעכב כדי לשלוט בהתנהגות) רכיבים של אימפולסיביות. הרציונל הבסיסי של פרוטוקול זה מעמת נושאים עם שני פרסים שונים הן בעוצמה והן עיכוב17. חלופה אחת מספק גמול מיידי קטן (הנקרא קטנים יותר מוקדם יותר, SS) ומספק השני פרס גדול אך מושהית (כינה גדולים יותר מאוחר יותר, LL). שיעור התגובות החלופה אס יכול לשמש מדד אימפולסיביות18. בחיזוק דיפרנציאלית של נהלים המחירים הנמוכים, הגורם של אימפולסיביות לפנות לבדיקה הוא עיכוב התגובה (קרי, חוסר היכולת לעכב את התגובות prepotent) כאשר קיימת אפשרות. עונש שלילי על להגיב לא הולם. הרציונל של פרוטוקול זה היא היכרות עם נושאים למצב שבו היא הדרך היחידה של קבלת תגמולים להשהות שלהם מגיבה19. לבסוף, הליך שלילי תכונה אפליה מוערך עיכוב התגובה כאשר אין עונש מפורשת על להגיב לא הולם. הרציונל של הפרוטוקול (הידוע גם בשם ממוזגים פבלוביות עיכוב או ה-A + AX-הליך) היא להעריך את היכולת של הנבדקים לעכב את תגובות מיותרות20.

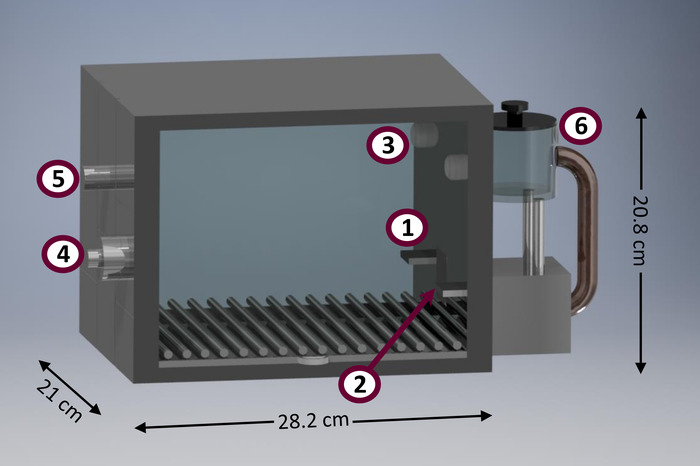

הליכים אלה להתבלט בהשוואה לאחרים כבעלי תכונות נוחות מסוימים. לדוגמה, ההליכים המובאים כאן מתאימים הנערך מיזוג מינימלית מאובזר צ’יימברס (הידוע גם בשם ‘ סקינר בתיבת’). איור 1 מציג דיאגרמה של תא מיזוג טיפוסי. מיזוג התאים הינם כלי מחקר שימושי עקב מספר יתרונות. הם מאפשרים אוסף אוטומטית של נפח גדול יחסית של נתונים, למקסם את מספר הנבדקים העריכו לאחדות של זמן ומרחב,21. יתר על כן, מחקרים התנהגותיים שנערכו ב מיזוג צ’יימברס דורשים התערבות מינימלית חוקר, אשר מפחית את הזמן ואת המאמץ המושקע על ידי צוות המעבדה, להבדיל משיטות אחרות (למשל, שאינה אוטומטית T-מבוכים, תיבות קבוצה-shifting) 21. צמצום ההתערבות חוקרים גם לסייע בהפחתת הטיה חוקרים, הפחתת תופעות של חוקרים עקומת למידה, ומתח הפחתה של טיפול-induced22. צ’יימברס מיזוג טיפוסי למדי מתוקננים כדי לשמש עם מכרסמים בגודל בינוני, כגון חולדות (ר’ norvegicus), אבל יכול להיות מועסק ללמוד taxa אחרים, כמו כיס בגודל דומה (למשל, albiventris ד, ול’ crassicaudata 23). יש גם מסחרי מיזוג צ’יימברס מותאם קטן יותר (למשל, עכברים [מ musculus]), גדולים יותר (למשל, אנושיות פרימטים) מינים. הגדרת וניצוח הפרוטוקולים שהוצגו במאמר זה דורשים ידע בתכנות מינימלי ולדרוש מספר נמוך של קלט השגה, התקני פלט, שלא כמו שיטות אלטרנטיביות מתוחכמות יותר (למשל, זמן התגובה טורי 5-בחירת פעילות [5- CSRTT]24 ו סימן-מעקב25).

איור 1: תרשים של מיזוג אב-טיפוס תא. הרכיבים העיקריים של התא מיזוג כוללים: ידית שמאל (1) (2) מזון קיבול (מצויד דיודות אינפרא-אדום לרוחב כדי לזהות ערכי ראש), אור focalized (3), (4) הרמקול צליל פליטה (אחוריים), (5) בית אור (אחוריים), (6) מזון מתקן. אנא לחץ כאן כדי להציג גירסה גדולה יותר של הדמות הזאת.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

המאמר הנוכחי מספק תיאור של מגוון שונות של פרוטוקולים לסינון אימפולסיביות אצל חולדות. נטען כי פרוטוקולים מסוימים אלה הם המועדף שלהם קלות תכנות וניתוח נתונים ולא דורשים מכשירים הפועלים, גירוי פחות מאשר חלופות אחרות. ישנם מספר שלבים קריטיים עבור יישום אפקטיבי של פרוטוקולים אלה, כגון (1) מניב …

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

ברצוננו להודות פלורנסה מאטה, מריה אלנה צ’אבס, מיגל בורגוס, אלחנדרו Tapia למתן סיוע טכני. אנחנו גם רוצים להודות שרה גורדון פרנסס להערות שימושי שלה על טיוטה הקודם של מאמר זה ולדימיר Orduña עבור באדיבות מתן נתונים גולמיים של נייר שפורסמו. תודה קלאודיו Nallen ליצירת הדיאגרמה באיור1. אנו מודים על Investigación דה Dirección של México דה אוניברסיטת Iberoamericana Ciudad למימון שירותי עריכה לשונית, הוידאו בהפקת הוצאות.

Materials

| 25 Pin Cables | Med Associates | SG-213F | Connect smart control cards to smart control panels |

| 40 Pin Ribbon Cable | Med Associates | DIG-700C | Connects the computer with the interface cabinet |

| Computer | Dell Computer Company | T8P8T-7G8MR-4YPQV-96C2F-7THHB | For controlling and monitoring protocols’ processes |

| Conductor Cables | Med Associates | SG-210CP-8 | Provide power to the smart control panels via the rack mount power supply |

| Food dispenser with pedestal | Med Associates | ENV-203M-45 (12937) | Silently provides 45 mg food pellets |

| Head-Entry Detector | Med Associates | ENV-254-CB | Uses an infrared photo-beam to detect head entries into the food receptacle |

| House Light | Med Associates | ENV-215M | For providing diffuse illumination inside the chamber |

| Interface Cabinet | Med Associates | SG-6080D | Pod that can hold up to eight smart control cards |

| Med-PC IV Software | Med Associates | SOF-735 | Translate codes into commands for operating outputs and recording/storing input information |

| Multiple tone generator | Med Associates | ENV-223 (597) | For controlling the frequency of the tones |

| Panel fillers | Med Associates | ENV-007-FP | For filling modular walls when devices are not used |

| Pellet Receptacle | Med Associates | ENV-200R2M | Receives and holds food pellets delivered by the dispenser |

| Rack Mount Power Supply | Med Associates | DIG-700F | Provides power to the interface cabinet |

| Retractable Lever | Med Associates | ENV-112CM (10455) | Detects lever-pressing responses; projects into the chamber or retracts as needed |

| Smart Control Cards | Med Associates | DIG-716 | Controls up to eight inputs and four outputs of a conditioning chamber |

| Smart Control Panels | Med Associates | SG-716 (3341) | Connect smart cards to the devices within the conditioning chambers |

| Speaker | Med Associates | ENV-224AM | For providing tones inside the chamber |

| Standard Modular Chambers for Rat | Med Associates | ENV-008 | Made of aluminum channels designed to hold modular devices |

| Standard sound-, light-, and temperature isolating shells | Med Associates | ENV-022MD | Serve to harbor each conditioning chamber |

| Stimulus Light | Med Associates | ENV-221M | For providing a round focalized light stimulus |

| Three Pin Cables | Med Associates | SG-216A-2 | Connects smart control panel with each of the input and output devices in the conditioning chambers |

References

- Loxton, N. J. The role of reward sensitivity and impulsivity in overeating and food addiction. Current Addiction Reports. 5 (2), 212-222 (2018).

- Richards, J. B., Gancarz, A. M., Hawk, L. W., Bardo, M. T., Fishbein, D. H., Milich, R. . Inhibitory control and drug abuse prevention. , (2011).

- Gullo, M. J., Loxton, N. J., Dawe, S. Impulsivity: Four ways five fectors are not basic to addiction. Addictive Behaviors. 39 (11), 1547-1556 (2014).

- Bari, A., Robbins, T. W. Inhibition and impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis of response control. Progress in Neurobiology. 108, 44-79 (2013).

- Dalley, J. W., Robbins, T. W. Fractionating impulsivity: neuropsychiatric implications. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 18 (3), 158-171 (2017).

- Sosa, R., dos Santos, C. V. Toward a unifying account of impulsivity and the development of self-control. Perspectives in Behavior Science. , 1-32 (2018).

- King, J. A., Tenney, J., Rossi, V., Colamussi, L., Burdick, S. Neural substrates underlying impulsivity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1008 (1), 160-169 (2003).

- Stayer, R., Ferring, D., Schmitt, M. J. States and traits in psychological assessment. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 8 (2), 79-98 (1992).

- Moeller, F. G., Barratt, E. S., Dougherty, D. M., Schmitz, J. M., Swann, A. C. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 158, 1783-1793 (2001).

- Evenden, J. L. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 146 (4), 348-361 (1999).

- Winstanley, C. A. The utility of rat models of impulsivity in developing pharmacotherapies for impulse control disorders. British Journal of Pharmacology. 164 (4), 1301-1321 (2011).

- Solanto, M. V., et al. The ecological validity of delay aversion and response inhibition as measures of impulsivity in AD/HD: A supplement to the NIMH multimodal treatment study of AD/HD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 29 (3), 215-218 (2001).

- van der Staay, F. J. Animal models of behavioral dysfunctions: Basic concepts and classifications, and an evaluation strategy. Brain Research Reviews. 52, 131-159 (2006).

- Hedge, C., Powell, G., Summer, P. The reliability paradox: Why robust cognitive tasks do not produce reliable individual differences. Behavioral Research Methods. , 1-21 (2017).

- Nakagawa, S., Schielzeth, H. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: A practical guide for biologists. Biological Reviews. 85, 935-956 (2010).

- Sjoberg, E. Logical fallacies in animal model research. Behavior and Brain Functions. 13 (1), (2017).

- Rachlin, H. Self-control: Beyond commitment. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 18 (01), 109 (1995).

- Logue, A. W. Research on self-control: An integrating framework. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 11 (04), 665 (1988).

- Kramer, T. J., Rilling, M. Differential reinforcement of low rates: A selective critique. Psychological Bulletin. 74 (4), 225-254 (1970).

- Sosa, R., dos Santos, C. V. Conditioned inhibition and its relationship to impulsivity: Empirical and theoretical considerations. The Psychological Record. , (2018).

- Gallistel, C. R., Balci, F., Freestone, D., Kheifets, A., King, A. Automated, quantitative cognitive/behavioral screening of mice: For genetics, pharmacology, animal cognition and undergraduate instruction. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (84), (2014).

- Skinner, B. F. A case history in scientific method. American Psychologist. 11 (5), 221-233 (1956).

- Papini, M. R. Associative learning in the marsupials Didelphis albiventris and Lutreolina crassicaudata. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 102 (1), 21-27 (1988).

- Leonard, J. A. 5 choice serial reaction apparatus. Medical Research Council of Applied Psychology Research. , 326-359 (1959).

- Robinson, T. E., Flagel, S. B. Dissociating the Predictive and Incentive Motivational Properties of Reward-Related Cues Through the Study of Individual Differences. Biological Psychiatry. 65 (10), 869-873 (2009).

- Charan, J., Kantharia, N. D. How to calculate sample size in animal studies?. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 4 (4), 303-306 (2013).

- Toth, L. A., Gardiner, T. W. Food and water restriction protocols: Physiological and behavioral considerations. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 39 (6), 9-17 (2000).

- Deluty, M. Z. Self-control and impulsiveness involving aversive events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 4, 250-266 (1978).

- Cabrera, F., Robayo-Castro, B., Covarrubias, P. The ‘huautli’ alternative: Amaranth as reinforcer in operant procedures. Revista Mexicana de Análisis de la Conducta. 36, 71-92 (2010).

- Ferster, C. B., Skinner, B. F. . Schedules of reinforcement. , (1957).

- Orduña, V., Valencia-Torres, L., Bouzas, A. DRL performance of spontaneously hypertensive rats: Dissociation of timing and inhibition of responses. Behavioural Brain Research. 201 (1), 158-165 (2009).

- Freestone, D. M., Balci, F., Simen, P., Church, R. Optimal response rates in humans and animals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior and Cognition. 41 (1), 39-51 (2015).

- Sanabria, F., Killeen, P. R. Evidence for impulsivity in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat drawn from complementary response-withholding tasks. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 4 (1), 7 (2008).

- van den Bergh, F. S., et al. Spontaneously hypertensive rats do not predict symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 83, 11 (2006).

- Topping, J. S., Pickering, J. W. Effects of punishing different bands of IRTs on DRL responding. Psychological Reports. 31 (19-22), (1972).

- Richards, J. B., Sabol, K. E., Seiden, L. S. DRL interresponse-time distributions: quantification by peak deviation analysis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 60 (2), 361-385 (1993).

- Orduña, V. Impulsivity and sensitivity to amount and delay of reinforcement in an animal model of ADHD. Behavioural Brain Research. 294, 62-71 (2015).

- Harmer, C. J., Phillips, G. D. Enhanced conditioned inhibition following repeated pretreatment with d -amphetamine. Psychopharmacology. 142 (2), 120-131 (1999).

- Lister, S., Pearce, J. M., Butcher, S. P., Collard, K. J., Foster, G. Acquisition of conditioned inhibition in rats is impaired by ablation of serotoninergic pathways. European Journal of Neuroscience. 8, 415-423 (1996).

- Meyer, H. C., Bucci, D. J. The contribution of medial prefrontal cortical regions to conditioned inhibition. Behavioral Neuroscience. 128 (6), 644-653 (2014).

- McNicol, D. . A primer of signal detection theory. , (1972).

- Carnero, S., Morís, J., Acebes, F., Loy, I. Percepción de la contingencia en ratas: Modulación fechneriana y metodología de la detección de señales. Revista Electrónica de Metodología Aplicada. 14 (2), (2009).

- López, H. H., Ettenberg, A. Dopamine antagonism attenuates the unconditioned incentive value of estrus female cues. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 68, 411-416 (2001).

- Schotte, A., Janssen, P. F. M., Megens, A. A. H. P., Leysen, J. E. Occupancy of central neurotransmitter receptors by risperidone, clozapine and haloperidol, measured ex vivo. Brain Research. 631 (2), 191-202 (1993).

- van Hest, A., van Haaren, F., van de Poll, N. Haloperidol, but not apomorphine, differentially affects low response rates of male and female wistar rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 29, 529-532 (1988).

- Finnegan, K. T., Ricaurte, G., Seiden, L. S., Schuster, C. R. Altered sensitivity to d-methylamphetamine, apomorphine, and haloperidol in rhesus monkeys depleted of caudate dopamine by repeated administration of d-methylamphetamine. Psychopharmacology. 77, 43-52 (1982).

- Britton, K. T., Koob, G. F. Effects of corticotropin releasing factor, desipramine and haloperidol on a DRL schedule of reinforcement. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 32, 967-970 (1989).

- Maricq, A. V., Church, R. The differential effects of haloperidol and metamphetamine on time estimation in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 79, 10-15 (1983).

- Dalley, J. W., et al. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 315, 1267-1270 (2007).

- Cole, B. J., Robbins, T. W. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the nucleus accumbens septi on performance of a 5-choice serial reaction time task in rats: Implications for theories of selective attention and arousal. Behavior and Brain Research. 33, 165-179 (1989).

- Reynolds, B., de Wit, H., Richards, J. B. Delay of gratification and delay discounting in rats. Behavioural Processes. 59 (3), 157-168 (2002).

- Evenden, J. L., Ryan, C. N. The pharmacology of impulsive behavior in rats: The effects of drugs on response choice with varying delays of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 128, 161-170 (1996).

- Autor, S. M., Hendry, D. P. . Conditioned reinforcement. , (1969).

- van den Broek, M. D., Bradshaw, C. M., Szabadi, E. Behaviour of ‘impulsive’ and ‘non-impulsive’ humans in a temporal differentiation schedule of reinforcement. Personality and Individual Differences. 8 (2), 233-239 (1987).

- McGuire, P. S., Seiden, L. S. The effects of tricyclicantidepressants on performance under a differential-reinforcement-of-low-rates schedule in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 214 (3), 635-641 (1980).

- O’Donnell, J. M., Seiden, L. S. Differential-reinforcement-of-low-rates 72-second schedule: Selective effects of antidepressant drugs. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 224 (1), 80-88 (1983).

- Seiden, L. S., Dahms, J. L., Shaughnessy, R. A. Behavioral screen for antidepressants: The effects of drugs and electroconvulsive shock on performance under a differential-reinforcement-of-low-rates schedule. Psychopharmacology. 86, 55-60 (1985).

- He, Z., Cassaday, H. J., Howard, R. C., Khalifa, N., Bonardi, C. Impaired Pavlovian conditioned inhibition in offenders with personality disorders. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 64 (12), 2334-2351 (2011).

- He, Z., Cassaday, H. J., Bonardi, C., Bibi, P. A. Do personality traits predict individual differences in excitatory and inhibitory learning?. Frontiers in Psychology. 4, 1-12 (2013).

- Bucci, D. J., Hopkins, M. E., Keene, C. S., Sharma, M., Orr, L. E. Sex differences in learning and inhibition in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 187 (1), 27-32 (2008).

- Gershon, J. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 5, 143-154 (2012).

- Mobini, S., et al. Effects of lesions of the orbitofrontal cortex on sensitivity to delayed and probabilistic reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 160 (3), 290-298 (2002).

- Bouton, M. E., Nelson, J. B. Context-specificity of target versus feature inhibition in a negative-feature discrimination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 20 (1), 51-65 (1994).

- Bouton, M. E., Nelson, J. B., Schmajuk, N., Holland, P. . Occasion setting: Associative learning and cognition in animals. , 69-112 (1998).

- Rescorla, R. A. Pavlovian conditioned inhibition. Psychological Bulletin. 72 (2), 77-94 (1969).

- Miller, R. R., Matzel, L. D., Bower, G. H. . The psychology of learning and motivation. , (1988).

- Williams, D. A., Overmier, J. B., Lolordo, V. M. A reevaluation of Rescorla’s early dictums about conditioned inhibition. Psychological Bulletin. 111 (2), 275-290 (1992).

- Papini, M. R., Bitterman, M. E. The two-test strategy in the study of inhibitory conditioning. Psychological Review. 97 (3), 396-403 (1993).

- Sosa, R., Ramírez, M. N. Conditioned inhibition: Critiques and controversies in the light of recent advances. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior and Cognition. , (2018).

- Fox, A. T., Hand, D. J., Reilly, M. P. Impulsive choice in a rodent model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behavioural Brain Research. 187, 146-152 (2008).

- Foscue, E. P., Wood, K. N., Schramm-Sapyta, N. L. Characterization of a semi-rapid method for assessing delay discounting in rodents. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 101, 187-192 (2012).

- Brucks, D., Marshall-Pescini, S., Wallis, L. J., Huber, L., Range, F. Measures of Dogs’ Inhibitory Control Abilities Do Not Correlate across Tasks. Frontiers in Psychology. 8, (2017).

- McDonald, J., Schleifer, L., Richards, J. B., de Wit, H. Effects of THC on Behavioral Measures of Impulsivity in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (7), 1356-1365 (2003).

- Reynolds, B., Ortengren, A., Richards, J. B., de Wit, H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: Personality and behavioral measures. Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (2), 305-315 (2006).

- Dellu-Hagedorn, F. Relationship between impulsivity, hyperactivity and working memory: a differential analysis in the rat. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2 (10), 18 (2006).

- López, P., Alba, R., Orduña, V. Individual differences in incentive salience attribution are not related to suboptimal choice in rats. Behavior and Brain Research. 341 (2), 71-78 (2017).

- Ho, M. Y., Al-Zahrani, S. S. A., Al-Ruwaitea, A. S. A., Bradshaw, C. M., Szabadi, E. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and impulse control: prospects for a behavioural analysis. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 12 (1), 68-78 (1998).

- Sagvolden, T., Russell, V. A., Aase, H., Johansen, E. B., Farshbaf, M. Rodent models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 57, 9 (2005).

- Tomie, A., Aguado, A. S., Pohorecky, L. A., Benjamin, D. Ethanol induces impulsive-like responding in a delay-of-reward operant choice procedure: impulsivity predicts autoshaping. Psychopharmacology. 139 (4), 376-382 (1998).

- Monterosso, J., Ainslie, G. Beyond discounting: possible experimental models of impulse control. Psychopharmacology. 146 (4), 339-347 (1999).

- Burguess, M. A., Rabbit, P. . Methodology of frontal and executive function. , 81-116 (1997).

- Watterson, E., Mazur, G. J., Sanabria, F. Validation of a method to assess ADHD-related impulsivity in animal models. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 252, 36-47 (2015).

- Hackenberg, T. D. Of pigeons and people: some observations on species differences in choice and self-control. Brazilian Journal of Behavior Analysis. 1 (2), 135-147 (2005).

- Asinof, S., Paine, T. A. The 5-choice serial reaction time task: A task of attention and impulse control for rodents. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (90), e51574 (2014).

- Masaki, D., et al. Relationship between limbic and cortical 5-HT neurotransmission and acquisition and reversal learning in a go/no-go task in rats. Psychopharmacology. 189, 249-258 (2006).

- Bari, A., et al. Prefrontal and monoaminergic contributions to stop-signal task performance in rats. The Journal of Neuroscience. 31, 9254-9263 (2011).

- Flagel, S. B., Watson, S. J., Robinson, T. E., Akil, H. Individual differences in the propensity to approach signals vs goals promote different adaptations in the dopamine system of rats. Psychopharmacology. 191, 599-607 (2007).

- Swann, A. C., Lijffijt, M., Lane, S. D., Steinberg, J. L., Moeller, F. G. Trait impulsivity and response inhibition in antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 43 (12), 1057-1063 (2009).

- Lawrence, A. J., Luty, J., Bogdan, N. A., Sahakian, B. J., Clark, L. Impulsivity and response inhibition in alcohol dependence and problem gambling. Psychopharmacology. 207 (1), 163-172 (2009).

- Dougherty, D. M., et al. Behavioral impulsivity paradigms: a comparison in hospitalized adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 44 (8), 1145-1157 (2003).

- Rosval, L., et al. Impulsivity in women with eating disorders: Problem of response inhibition, planning, or attention. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 39 (7), 590-593 (2006).

- Huddy, V. C., et al. Reflection impulsivity and response inhibition in first-episode psychosis: relationship to cannabis use. Psychological Medicine. 43 (10), 2097-2107 (2013).