评估大鼠冲动不同表现的三个实验室程序

Summary

我们提出了三个协议, 评估不同形式的冲动在大鼠和其他小型哺乳动物。时间选择程序评估延迟结果的价值折现的趋势。低率和特征负歧视的差异强化分别评价反应抑制能力, 对不适当的反应进行惩罚和不惩罚。

Abstract

本文为三种基于条件的大鼠冲动评价方案的传导和分析提供了指导。冲动是一个有意义的概念, 因为它与人类的精神状况和非人类动物的不适应行为有关。人们认为冲动是由不同的因素组成的。有一些实验室协议是为使用标准化自动化设备评估这些因素中的每一个因素而设计的。延迟折扣与无法被延迟结果所驱动有关。这一因素是通过时际选择协议来评估的, 其中包括向个人提供一个选择情况, 包括立即奖励和更大但延迟的奖励。反应抑制不足与无法抑制前作要反应有关。低速率 (DLR) 和特征负歧视协议的差异增强评估脉冲的反应抑制缺陷因子。前者对有动机的个人施加了一个条件, 即大多数人等待最低限度的时间才能得到答复的奖励。后者评价个人在发出没有粮食的信号时不寻求粮食的能力。这些协议的目的是构建一个客观的冲动定量测量, 用于进行跨物种比较, 允许转化研究的可能性。这些特定协议的优点包括易于设置和应用, 这源于所需设备的数量相对较少以及这些协议的自动化性质。

Introduction

冲动可以被概念化为与不适应结果1相关的行为维度。尽管这一术语被广泛使用, 但对其确切定义没有普遍共识。事实上, 一些作者通过列举冲动行为或其后果的例子来定义冲动, 而不是描述决定这种现象的不同方面。例如, 冲动被认为是指无法等待、计划、抑制前会行为或对延迟结果不敏感 2, 它被认为是成瘾行为的核心弱点3。巴里和罗宾斯4将冲动描述为强冲动的共同发生, 由沉积和情景变量以及功能失调的抑制过程触发。Dalley 和 Robbins 提供了不同的定义, 他们指出, 冲动可被视为在没有适当见解的情况下采取迅速、往往是过早行动的倾向.然而, 另一个定义的冲动, 由 Sosa 和 dos Santos6提出, 是一种行为倾向, 偏离了一个有机体最大限度地发挥可用的回报, 由于获得的控制, 发挥了对生物体的反应的刺激顺便说一句与这些奖励相关。

由于与冲动相关的行为过程, 其神经生理底物涉及与动机行为、决策和奖励价值相同的结构。这得到了研究的支持, 这些研究表明, 皮质纹状体通路 (例如, 伏隔核 [NAc]、前额叶皮质 [PFC]、杏仁核和尾状蛋白 putamen [CPU]) 以及上升的单胺能神经递质系统的结构参与其中。在冲动行为的表示 7.然而, 脉冲的神经底物比这更复杂。尽管 NAc 和 PFC 参与了冲动行为, 但这些结构是更复杂的系统的一部分, 并且由具有不同功能的子结构组成 (有关更详细的文档, 请参阅 D放利和 Robbins5)。

无论对其性质和生物底物的争议如何, 已知这种行为维度因个人而异, 在这种情况下, 它可以被视为一种特征, 也可以被认为是个体内部, 在这种情况下, 它可以被视为状态8。长期以来, 冲动一直被认为是某些精神状况的一个特征, 如注意力缺陷多动障碍 (ADHD)、药物滥用和躁狂发作 9。人们似乎普遍认为, 冲动是由多种不可分离的因素构成的, 包括不愿意等待 (即延迟打折)、没有能力克制前作效应的反应 (即抑制性缺陷)、难以关注相关因素。信息 (即注意力不集中), 以及处于危险境地的倾向 (即寻求感觉)5、10、11.这些因素中的每一个都可以通过特殊的行为任务来评估, 这些任务通常被分配到两个广泛的类别: 选择和反应抑制 (这些因素在每个作者的分类之间可能有不同的标签)。这类行为任务的一些重要特征是, 它们可以应用于多个动物物种2,并允许在可控实验室条件下研究冲动。

用实验室非人类动物对行为维度进行建模有许多优点, 包括可以测量具体的、可操作的行为倾向, 从而使研究人员能够在很大程度上减少混淆变量 (例如,由过去的生活事件污染 4), 并实施实验操作, 如慢性药理管理, 执行神经毒性病变, 或遗传操作。这些协议的多数有模拟版本为人, 使比较容易5。重要的是, 在人类中使用这些实验室协议的类似物可以有效地诊断精神障碍 (特别是当应用了一个以上的协议12) 的精神状况。

与任何其他心理测量一样, 评估冲动的实验室规程必须符合特定标准, 以实现深入了解所研究现象的目标。要被认为是一种适当的冲动行为模型, 实验室协议应该是可靠的, 并具有 (至少在一定程度上) 的面、构造和预测有效性 13.可靠性可能意味着, 如果进行两次或两次以上的操作, 对测量的影响将会复制, 或者测量在不同的情况下或在 14、15、15之间是一致的。前一种特点对实验研究特别有用, 而后一种特点对相关研究特别有用。人脸有效性是指测量到的东西与应该建模的现象相似的程度, 例如, 被相同变量的影响。预测有效性是指度量在协议中预测未来性能的能力, 其目的是测量相同或相关的构造。最后, 构造有效性是指协议是否再现了理论上合理的行为, 即假定在所研究的现象中涉及的过程或过程。然而, 尽管这些都是非常可取的功能, 但在声明协议完全基于这些标准16是有效的时, 应该谨慎。

有几种测量实验室环境中的脉冲的方案。然而, 本文只提出了三种方法: 时际选择、低比率的差异强化和特征负歧视。时际程序的目的是评估延迟折扣 (即延迟结果控制行为的困难) 冲动的组成部分。该议定书的基本理由是面对两个在规模和延迟上都不同的奖励对象。一种替代方案提供了一个小的即时奖励 (称为更早, ss) 和另一个提供一个更大的, 但延迟的奖励 (称为更大的后, ll)。对 SS 替代品的反应比例可作为冲动指数 18。在对低比率程序的差异强化中, 要评估的冲动因素是反应抑制 (即在对不适当的反应有消极惩罚意外情况时, 无法抑制先前的反应)。该协议的理由是向主体介绍了一种情况, 即获得奖励的唯一途径是暂停其作出答复的19项。最后, 特征负歧视程序在对不恰当反应没有明确处罚的情况下, 对反应抑制进行评价。该协议的基本原理 (也称为 Pavlovian 条件抑制或 a +/AX-TOR 程序) 是评估受试者是否有能力不作出不必要的反应20。

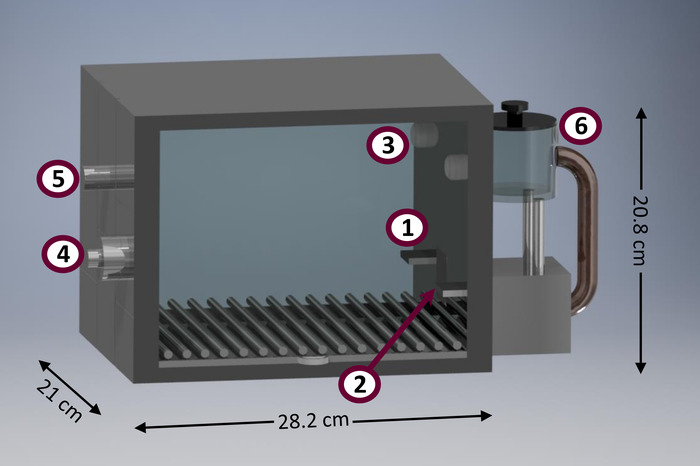

与其他程序相比, 这些程序具有一些方便的功能。例如, 这里介绍的程序适用于在设备最少的空调室 (也称为 “斯金纳盒子”) 中进行。图 1显示了一个典型的调节室的示意图。调理室是有用的研究工具, 由于一些优点。它们允许自动收集相对较大的数据量, 最大限度地增加为时间和空间统一而评估的主题数量21。此外, 在调理室进行的行为研究需要很少的研究人员干预, 这减少了实验室工作人员投入的时间和精力, 这与其他可用的方法 (例如, 非自动 t 形迷宫、装盒) 不同。21. 尽量减少研究人员的干预也有助于减少研究人员的偏见, 减少研究人员学习曲线的影响, 减少手部引起的压力 22.典型的调理室是相当标准化的, 可用于中等大小的啮齿类动物, 如老鼠 (r. norvegicus), 但可用于研究其他分类群, 如类似大小的有袋动物 (如d. albi腹 Oris 和 l. crassicaudata )23). 还有适合较小 (如小鼠 [肌肉组织]) 和较大 (如非人类灵长类动物) 的商业调理室。设置和执行本文中介绍的协议需要最少的编程技能, 并且需要相当少数量的可实现的输入和输出设备, 这与更复杂的替代方法 (例如, 5 选择的串行反应时间任务 [5-CSRTT] 24和信号跟踪25)。

图 1: 调节室原型图.调节室的主要部件包括: (1) 左杠杆, (2) 食品容器 (配备侧向红外二极管, 以检测头部入口), (3) 聚焦光, (4) 扬声器调音发射 (后视镜), (5) 房屋灯 (后视), (6) 食品分配器。请点击这里查看此图的较大版本.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

本文介绍了各种用于大鼠冲动筛查的协议。有人认为, 这些特定的协议因易于编程和数据分析而受到青睐, 比其他可用的替代方案所需的操作和刺激设备更少。有效实施这些协议有几个关键步骤, 例如: (1) 产生研究问题; (2) 选择适当的研究设计; (3) 规划选定的协议; (4) 进行研究, (5) 收集数据, (6)分析数据, 并 (7) 解释数据。充分发展研究问题有助于缩小处理这一问题的可能方法的范围。一个有重点的?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

我们要感谢 Florencia Mata、María Elena Chávez、Miguel Burgos 和 Alejandro Tapia 提供的技术援助。我们还要感谢 Sarah Gordon Frances 对本条先前草案的有益评论, 并感谢弗拉基米尔·奥多尼亚善意地提供了发表论文的原始数据。感谢克劳迪奥·纳伦创建了图 1中的关系图。我们感谢伊比利亚-美洲城市大学调查指导委员会提供资金证明编辑服务和录像制作费用。

Materials

| 25 Pin Cables | Med Associates | SG-213F | Connect smart control cards to smart control panels |

| 40 Pin Ribbon Cable | Med Associates | DIG-700C | Connects the computer with the interface cabinet |

| Computer | Dell Computer Company | T8P8T-7G8MR-4YPQV-96C2F-7THHB | For controlling and monitoring protocols’ processes |

| Conductor Cables | Med Associates | SG-210CP-8 | Provide power to the smart control panels via the rack mount power supply |

| Food dispenser with pedestal | Med Associates | ENV-203M-45 (12937) | Silently provides 45 mg food pellets |

| Head-Entry Detector | Med Associates | ENV-254-CB | Uses an infrared photo-beam to detect head entries into the food receptacle |

| House Light | Med Associates | ENV-215M | For providing diffuse illumination inside the chamber |

| Interface Cabinet | Med Associates | SG-6080D | Pod that can hold up to eight smart control cards |

| Med-PC IV Software | Med Associates | SOF-735 | Translate codes into commands for operating outputs and recording/storing input information |

| Multiple tone generator | Med Associates | ENV-223 (597) | For controlling the frequency of the tones |

| Panel fillers | Med Associates | ENV-007-FP | For filling modular walls when devices are not used |

| Pellet Receptacle | Med Associates | ENV-200R2M | Receives and holds food pellets delivered by the dispenser |

| Rack Mount Power Supply | Med Associates | DIG-700F | Provides power to the interface cabinet |

| Retractable Lever | Med Associates | ENV-112CM (10455) | Detects lever-pressing responses; projects into the chamber or retracts as needed |

| Smart Control Cards | Med Associates | DIG-716 | Controls up to eight inputs and four outputs of a conditioning chamber |

| Smart Control Panels | Med Associates | SG-716 (3341) | Connect smart cards to the devices within the conditioning chambers |

| Speaker | Med Associates | ENV-224AM | For providing tones inside the chamber |

| Standard Modular Chambers for Rat | Med Associates | ENV-008 | Made of aluminum channels designed to hold modular devices |

| Standard sound-, light-, and temperature isolating shells | Med Associates | ENV-022MD | Serve to harbor each conditioning chamber |

| Stimulus Light | Med Associates | ENV-221M | For providing a round focalized light stimulus |

| Three Pin Cables | Med Associates | SG-216A-2 | Connects smart control panel with each of the input and output devices in the conditioning chambers |

References

- Loxton, N. J. The role of reward sensitivity and impulsivity in overeating and food addiction. Current Addiction Reports. 5 (2), 212-222 (2018).

- Richards, J. B., Gancarz, A. M., Hawk, L. W., Bardo, M. T., Fishbein, D. H., Milich, R. . Inhibitory control and drug abuse prevention. , (2011).

- Gullo, M. J., Loxton, N. J., Dawe, S. Impulsivity: Four ways five fectors are not basic to addiction. Addictive Behaviors. 39 (11), 1547-1556 (2014).

- Bari, A., Robbins, T. W. Inhibition and impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis of response control. Progress in Neurobiology. 108, 44-79 (2013).

- Dalley, J. W., Robbins, T. W. Fractionating impulsivity: neuropsychiatric implications. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 18 (3), 158-171 (2017).

- Sosa, R., dos Santos, C. V. Toward a unifying account of impulsivity and the development of self-control. Perspectives in Behavior Science. , 1-32 (2018).

- King, J. A., Tenney, J., Rossi, V., Colamussi, L., Burdick, S. Neural substrates underlying impulsivity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1008 (1), 160-169 (2003).

- Stayer, R., Ferring, D., Schmitt, M. J. States and traits in psychological assessment. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 8 (2), 79-98 (1992).

- Moeller, F. G., Barratt, E. S., Dougherty, D. M., Schmitz, J. M., Swann, A. C. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 158, 1783-1793 (2001).

- Evenden, J. L. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 146 (4), 348-361 (1999).

- Winstanley, C. A. The utility of rat models of impulsivity in developing pharmacotherapies for impulse control disorders. British Journal of Pharmacology. 164 (4), 1301-1321 (2011).

- Solanto, M. V., et al. The ecological validity of delay aversion and response inhibition as measures of impulsivity in AD/HD: A supplement to the NIMH multimodal treatment study of AD/HD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 29 (3), 215-218 (2001).

- van der Staay, F. J. Animal models of behavioral dysfunctions: Basic concepts and classifications, and an evaluation strategy. Brain Research Reviews. 52, 131-159 (2006).

- Hedge, C., Powell, G., Summer, P. The reliability paradox: Why robust cognitive tasks do not produce reliable individual differences. Behavioral Research Methods. , 1-21 (2017).

- Nakagawa, S., Schielzeth, H. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: A practical guide for biologists. Biological Reviews. 85, 935-956 (2010).

- Sjoberg, E. Logical fallacies in animal model research. Behavior and Brain Functions. 13 (1), (2017).

- Rachlin, H. Self-control: Beyond commitment. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 18 (01), 109 (1995).

- Logue, A. W. Research on self-control: An integrating framework. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 11 (04), 665 (1988).

- Kramer, T. J., Rilling, M. Differential reinforcement of low rates: A selective critique. Psychological Bulletin. 74 (4), 225-254 (1970).

- Sosa, R., dos Santos, C. V. Conditioned inhibition and its relationship to impulsivity: Empirical and theoretical considerations. The Psychological Record. , (2018).

- Gallistel, C. R., Balci, F., Freestone, D., Kheifets, A., King, A. Automated, quantitative cognitive/behavioral screening of mice: For genetics, pharmacology, animal cognition and undergraduate instruction. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (84), (2014).

- Skinner, B. F. A case history in scientific method. American Psychologist. 11 (5), 221-233 (1956).

- Papini, M. R. Associative learning in the marsupials Didelphis albiventris and Lutreolina crassicaudata. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 102 (1), 21-27 (1988).

- Leonard, J. A. 5 choice serial reaction apparatus. Medical Research Council of Applied Psychology Research. , 326-359 (1959).

- Robinson, T. E., Flagel, S. B. Dissociating the Predictive and Incentive Motivational Properties of Reward-Related Cues Through the Study of Individual Differences. Biological Psychiatry. 65 (10), 869-873 (2009).

- Charan, J., Kantharia, N. D. How to calculate sample size in animal studies?. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 4 (4), 303-306 (2013).

- Toth, L. A., Gardiner, T. W. Food and water restriction protocols: Physiological and behavioral considerations. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 39 (6), 9-17 (2000).

- Deluty, M. Z. Self-control and impulsiveness involving aversive events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 4, 250-266 (1978).

- Cabrera, F., Robayo-Castro, B., Covarrubias, P. The ‘huautli’ alternative: Amaranth as reinforcer in operant procedures. Revista Mexicana de Análisis de la Conducta. 36, 71-92 (2010).

- Ferster, C. B., Skinner, B. F. . Schedules of reinforcement. , (1957).

- Orduña, V., Valencia-Torres, L., Bouzas, A. DRL performance of spontaneously hypertensive rats: Dissociation of timing and inhibition of responses. Behavioural Brain Research. 201 (1), 158-165 (2009).

- Freestone, D. M., Balci, F., Simen, P., Church, R. Optimal response rates in humans and animals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior and Cognition. 41 (1), 39-51 (2015).

- Sanabria, F., Killeen, P. R. Evidence for impulsivity in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat drawn from complementary response-withholding tasks. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 4 (1), 7 (2008).

- van den Bergh, F. S., et al. Spontaneously hypertensive rats do not predict symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 83, 11 (2006).

- Topping, J. S., Pickering, J. W. Effects of punishing different bands of IRTs on DRL responding. Psychological Reports. 31 (19-22), (1972).

- Richards, J. B., Sabol, K. E., Seiden, L. S. DRL interresponse-time distributions: quantification by peak deviation analysis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 60 (2), 361-385 (1993).

- Orduña, V. Impulsivity and sensitivity to amount and delay of reinforcement in an animal model of ADHD. Behavioural Brain Research. 294, 62-71 (2015).

- Harmer, C. J., Phillips, G. D. Enhanced conditioned inhibition following repeated pretreatment with d -amphetamine. Psychopharmacology. 142 (2), 120-131 (1999).

- Lister, S., Pearce, J. M., Butcher, S. P., Collard, K. J., Foster, G. Acquisition of conditioned inhibition in rats is impaired by ablation of serotoninergic pathways. European Journal of Neuroscience. 8, 415-423 (1996).

- Meyer, H. C., Bucci, D. J. The contribution of medial prefrontal cortical regions to conditioned inhibition. Behavioral Neuroscience. 128 (6), 644-653 (2014).

- McNicol, D. . A primer of signal detection theory. , (1972).

- Carnero, S., Morís, J., Acebes, F., Loy, I. Percepción de la contingencia en ratas: Modulación fechneriana y metodología de la detección de señales. Revista Electrónica de Metodología Aplicada. 14 (2), (2009).

- López, H. H., Ettenberg, A. Dopamine antagonism attenuates the unconditioned incentive value of estrus female cues. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 68, 411-416 (2001).

- Schotte, A., Janssen, P. F. M., Megens, A. A. H. P., Leysen, J. E. Occupancy of central neurotransmitter receptors by risperidone, clozapine and haloperidol, measured ex vivo. Brain Research. 631 (2), 191-202 (1993).

- van Hest, A., van Haaren, F., van de Poll, N. Haloperidol, but not apomorphine, differentially affects low response rates of male and female wistar rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 29, 529-532 (1988).

- Finnegan, K. T., Ricaurte, G., Seiden, L. S., Schuster, C. R. Altered sensitivity to d-methylamphetamine, apomorphine, and haloperidol in rhesus monkeys depleted of caudate dopamine by repeated administration of d-methylamphetamine. Psychopharmacology. 77, 43-52 (1982).

- Britton, K. T., Koob, G. F. Effects of corticotropin releasing factor, desipramine and haloperidol on a DRL schedule of reinforcement. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 32, 967-970 (1989).

- Maricq, A. V., Church, R. The differential effects of haloperidol and metamphetamine on time estimation in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 79, 10-15 (1983).

- Dalley, J. W., et al. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 315, 1267-1270 (2007).

- Cole, B. J., Robbins, T. W. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the nucleus accumbens septi on performance of a 5-choice serial reaction time task in rats: Implications for theories of selective attention and arousal. Behavior and Brain Research. 33, 165-179 (1989).

- Reynolds, B., de Wit, H., Richards, J. B. Delay of gratification and delay discounting in rats. Behavioural Processes. 59 (3), 157-168 (2002).

- Evenden, J. L., Ryan, C. N. The pharmacology of impulsive behavior in rats: The effects of drugs on response choice with varying delays of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 128, 161-170 (1996).

- Autor, S. M., Hendry, D. P. . Conditioned reinforcement. , (1969).

- van den Broek, M. D., Bradshaw, C. M., Szabadi, E. Behaviour of ‘impulsive’ and ‘non-impulsive’ humans in a temporal differentiation schedule of reinforcement. Personality and Individual Differences. 8 (2), 233-239 (1987).

- McGuire, P. S., Seiden, L. S. The effects of tricyclicantidepressants on performance under a differential-reinforcement-of-low-rates schedule in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 214 (3), 635-641 (1980).

- O’Donnell, J. M., Seiden, L. S. Differential-reinforcement-of-low-rates 72-second schedule: Selective effects of antidepressant drugs. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 224 (1), 80-88 (1983).

- Seiden, L. S., Dahms, J. L., Shaughnessy, R. A. Behavioral screen for antidepressants: The effects of drugs and electroconvulsive shock on performance under a differential-reinforcement-of-low-rates schedule. Psychopharmacology. 86, 55-60 (1985).

- He, Z., Cassaday, H. J., Howard, R. C., Khalifa, N., Bonardi, C. Impaired Pavlovian conditioned inhibition in offenders with personality disorders. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 64 (12), 2334-2351 (2011).

- He, Z., Cassaday, H. J., Bonardi, C., Bibi, P. A. Do personality traits predict individual differences in excitatory and inhibitory learning?. Frontiers in Psychology. 4, 1-12 (2013).

- Bucci, D. J., Hopkins, M. E., Keene, C. S., Sharma, M., Orr, L. E. Sex differences in learning and inhibition in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 187 (1), 27-32 (2008).

- Gershon, J. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 5, 143-154 (2012).

- Mobini, S., et al. Effects of lesions of the orbitofrontal cortex on sensitivity to delayed and probabilistic reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 160 (3), 290-298 (2002).

- Bouton, M. E., Nelson, J. B. Context-specificity of target versus feature inhibition in a negative-feature discrimination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 20 (1), 51-65 (1994).

- Bouton, M. E., Nelson, J. B., Schmajuk, N., Holland, P. . Occasion setting: Associative learning and cognition in animals. , 69-112 (1998).

- Rescorla, R. A. Pavlovian conditioned inhibition. Psychological Bulletin. 72 (2), 77-94 (1969).

- Miller, R. R., Matzel, L. D., Bower, G. H. . The psychology of learning and motivation. , (1988).

- Williams, D. A., Overmier, J. B., Lolordo, V. M. A reevaluation of Rescorla’s early dictums about conditioned inhibition. Psychological Bulletin. 111 (2), 275-290 (1992).

- Papini, M. R., Bitterman, M. E. The two-test strategy in the study of inhibitory conditioning. Psychological Review. 97 (3), 396-403 (1993).

- Sosa, R., Ramírez, M. N. Conditioned inhibition: Critiques and controversies in the light of recent advances. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior and Cognition. , (2018).

- Fox, A. T., Hand, D. J., Reilly, M. P. Impulsive choice in a rodent model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behavioural Brain Research. 187, 146-152 (2008).

- Foscue, E. P., Wood, K. N., Schramm-Sapyta, N. L. Characterization of a semi-rapid method for assessing delay discounting in rodents. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 101, 187-192 (2012).

- Brucks, D., Marshall-Pescini, S., Wallis, L. J., Huber, L., Range, F. Measures of Dogs’ Inhibitory Control Abilities Do Not Correlate across Tasks. Frontiers in Psychology. 8, (2017).

- McDonald, J., Schleifer, L., Richards, J. B., de Wit, H. Effects of THC on Behavioral Measures of Impulsivity in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (7), 1356-1365 (2003).

- Reynolds, B., Ortengren, A., Richards, J. B., de Wit, H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: Personality and behavioral measures. Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (2), 305-315 (2006).

- Dellu-Hagedorn, F. Relationship between impulsivity, hyperactivity and working memory: a differential analysis in the rat. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2 (10), 18 (2006).

- López, P., Alba, R., Orduña, V. Individual differences in incentive salience attribution are not related to suboptimal choice in rats. Behavior and Brain Research. 341 (2), 71-78 (2017).

- Ho, M. Y., Al-Zahrani, S. S. A., Al-Ruwaitea, A. S. A., Bradshaw, C. M., Szabadi, E. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and impulse control: prospects for a behavioural analysis. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 12 (1), 68-78 (1998).

- Sagvolden, T., Russell, V. A., Aase, H., Johansen, E. B., Farshbaf, M. Rodent models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 57, 9 (2005).

- Tomie, A., Aguado, A. S., Pohorecky, L. A., Benjamin, D. Ethanol induces impulsive-like responding in a delay-of-reward operant choice procedure: impulsivity predicts autoshaping. Psychopharmacology. 139 (4), 376-382 (1998).

- Monterosso, J., Ainslie, G. Beyond discounting: possible experimental models of impulse control. Psychopharmacology. 146 (4), 339-347 (1999).

- Burguess, M. A., Rabbit, P. . Methodology of frontal and executive function. , 81-116 (1997).

- Watterson, E., Mazur, G. J., Sanabria, F. Validation of a method to assess ADHD-related impulsivity in animal models. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 252, 36-47 (2015).

- Hackenberg, T. D. Of pigeons and people: some observations on species differences in choice and self-control. Brazilian Journal of Behavior Analysis. 1 (2), 135-147 (2005).

- Asinof, S., Paine, T. A. The 5-choice serial reaction time task: A task of attention and impulse control for rodents. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (90), e51574 (2014).

- Masaki, D., et al. Relationship between limbic and cortical 5-HT neurotransmission and acquisition and reversal learning in a go/no-go task in rats. Psychopharmacology. 189, 249-258 (2006).

- Bari, A., et al. Prefrontal and monoaminergic contributions to stop-signal task performance in rats. The Journal of Neuroscience. 31, 9254-9263 (2011).

- Flagel, S. B., Watson, S. J., Robinson, T. E., Akil, H. Individual differences in the propensity to approach signals vs goals promote different adaptations in the dopamine system of rats. Psychopharmacology. 191, 599-607 (2007).

- Swann, A. C., Lijffijt, M., Lane, S. D., Steinberg, J. L., Moeller, F. G. Trait impulsivity and response inhibition in antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 43 (12), 1057-1063 (2009).

- Lawrence, A. J., Luty, J., Bogdan, N. A., Sahakian, B. J., Clark, L. Impulsivity and response inhibition in alcohol dependence and problem gambling. Psychopharmacology. 207 (1), 163-172 (2009).

- Dougherty, D. M., et al. Behavioral impulsivity paradigms: a comparison in hospitalized adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 44 (8), 1145-1157 (2003).

- Rosval, L., et al. Impulsivity in women with eating disorders: Problem of response inhibition, planning, or attention. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 39 (7), 590-593 (2006).

- Huddy, V. C., et al. Reflection impulsivity and response inhibition in first-episode psychosis: relationship to cannabis use. Psychological Medicine. 43 (10), 2097-2107 (2013).