ウィノグラツキーカラムの作成:堆積物サンプル中の微生物種を濃縮する方法

English

Share

Overview

ソース: エリザベス・スーター1, クリストファー・コルボ1, ジョナサン・ブレイズ1

1ワーグナーカレッジ生物科学科、1キャンパスロード、スタテンアイランドニューヨーク、10301

ウィノグラツキーのコラムは、堆積物微生物群集、特に硫黄循環に関与する人々を豊かにするために使用される、小型で囲まれた生態系です。このカラムは1880年代にセルゲイ・ウィノグラツキーによって最初に使用され、以来、光合成器、硫黄酸化剤、硫酸還元剤、メタンゲン、鉄酸化剤、窒素などの生物地球化学に関与する多くの多様な微生物の研究に適用されています。サイクラー、およびより多く(1,2)。

地球上の微生物の大半は、試験管やペトリ皿(3)で単離できないことを意味し、培養不可能と考えられています。これは、微生物が特定の代謝産物のために他の人に依存することを含む多くの要因によるものです。ウィノグラツキーのカラムの条件は、他の生物との相互作用を含む微生物の自然生息地を密接に模倣し、実験室で成長することを可能にする。そのため、この技術は、科学者がこれらの生物を研究し、それらが単独で成長することなく、地球の生物地球化学サイクルにとってどのように重要であるかを理解することを可能にします。

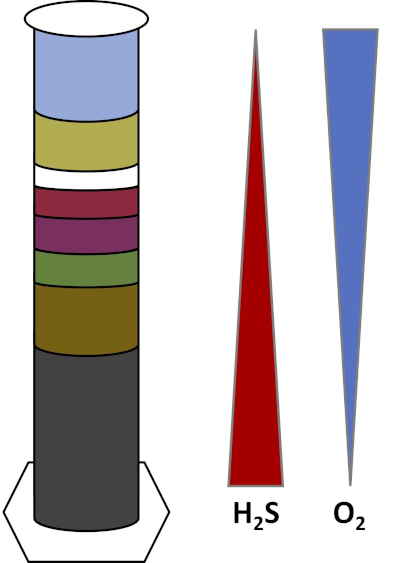

地球の環境は、土壌、海水、雲、深海堆積物など、あらゆる種類の生息地で繁栄する微生物でいっぱいです。すべての生息地では、微生物はお互いに依存しています。微生物が成長するにつれて、糖などの炭素が豊富な燃料や栄養素、ビタミン、酸素などの気道ガスなど、特定の基質を消費します。これらの重要な資源がなくなったら、異なる代謝ニーズを持つ異なる微生物が咲き、繁栄することができます。たとえば、Winogradsky 列では、微生物はまずカラムの下層の酸素を枯渇させながら、追加された有機材料を消費します。酸素が使い切られると、嫌気性生物が引き継ぎ、異なる有機材料を消費することができます。時間の経過とともに異なる微生物群相のこの連続的な発達は、継承(4)と呼ばれる。微生物の継承は、微生物の活動が堆積物の化学を変化させ、他の微生物の活動などに影響を与えるウィノグラツキーカラムで重要です。土壌や堆積物の多くの微生物も、基板の濃度に基づいて2種類の生息地間の遷移ゾーンである勾配に沿って生息しています(5)。グラデーションの正しい場所で、微生物は異なる基板の最適な量を受け取ることができます。ウィノグラツキーカラムが発達するにつれて、特に酸素と硫化物において、これらの自然勾配を模倣し始める(図1)。

図 1:ウィノグラツキーカラムで発生する酸素(O2)および硫化物(H2S)勾配の表現。

ウィノグラツキーのカラムでは、池や湿地の泥と水が透明な柱に混入し、通常は光の中でインキュベートすることができます。追加の基板は、通常、セルロース、および硫黄の形で、炭素のコミュニティソースを与えるために列に追加されます。フォトシンセサイザーは、通常、堆積物の最上層で成長し始めます。これらの光合成微生物は、酸素を産生し、緑または赤褐色の層として現れるシアノバクテリアからなる(図2、表1)。光合成は酸素を生成しますが、酸素は水にあまり溶け込んでおらず、この層の下に減少します(図1)。これは、最上層の高濃度の酸素から下層のゼロ酸素に至るまで、酸素の勾配を作成します。酸素化層は好気性層と呼ばれ、酸素のない層は嫌気性層と呼ばれています。

嫌気性層では、利用可能な基板の種類と量、初期微生物の供給源、および堆積物の多孔性に応じて、多くの異なる微生物群集が増殖する可能性があります。コラムの下部には、嫌気的に有機物を分解する生物が繁栄します。微生物発酵は、セルロースの分解から有機酸を生成します。これらの有機酸は、硫酸塩を使用してそれらの有機物を酸化し、副産物として硫化物を生成する硫酸塩還元剤によって使用することができます。硫酸塩還元器の活性は、鉄と硫化物が黒い硫化物鉱物を形成するために反応するため、堆積物が黒くなる場合に示される(図2、表1)。また、硫化物も上向きに拡散し、カラムの下部に硫化物濃度が高く、カラムの上部が低い別の勾配を作成します(図1)。

カラムの中央付近では、硫黄酸化剤は、上からの酸素の供給と下からの硫化物を利用します。光の適切な量で、光合成硫黄酸化剤は、これらの層で開発することができます。これらの生物は、緑と紫の硫黄細菌として知られており、しばしば緑色、紫色、または紫色のフィラメントやしみとして現れます(図2、表1)。緑色の硫黄細菌は硫化物に対する耐性が高く、通常は紫色の硫黄細菌のすぐ下の層で発症する。紫色の硫黄細菌の上に、紫色の非硫黄細菌も発症する可能性があります。これらの生物は、硫化物の代わりに電子ドナーとして有機酸を使用して光合成し、しばしば赤、紫、オレンジ、または茶色の層として現れます。非光合成硫黄酸化剤は紫色の非硫黄細菌の上に発症する可能性があり、これらは通常白いフィラメントとして現れます(図2、表1)。さらに、ウィノグラツキー列にも気泡が形成される場合があります。好気性層の気泡は、シアノバクテリアによる酸素の産生を示す。嫌気性層の気泡は、嫌気的に有機物を分解し、副産物としてメタンを形成するメタノゲンの活性に起因する可能性が高い。

| 列内の位置 | 機能グループ | 生物の例 | ビジュアルインジケータ |

| ページのトップへ | フォトシンスサイザー | シアノ バクテリア | 緑または赤褐色の層。時々酸素の泡。 |

| 非光合成硫黄酸化剤 | ベッジアトア,ティオバシラス | 白い層。 | |

| 紫色の非硫黄細菌 | ロドミクロビウム、ロドスピリラム、ロドプスオドモナス | 赤、紫、オレンジ、または茶色のレイヤー。 | |

| 紫色の硫黄細菌 | クロマチウム | 紫、または紫赤のレイヤー。 | |

| 緑硫黄細菌 | クロロビウム | 緑のレイヤー。 | |

| 硫酸還元菌 | デスルフォビブリオ、デスルホトマキュラム、デスルフォバクター、デスルフロモナス | 黒い層。 | |

| 下部 | メタノゲン | メタノコッカス,メタノサルシナ | 時々メタンの泡。 |

表 1:古典的なウィノグラツキーの列に上から下に現れるかもしれない細菌の主なグループ。各グループの生物の例を示し、生物の各層の視覚的指標を列挙する。ペリーら(2002年)とローガンら(2005年)に基づく。

Procedure

Results

In this experiment, water and sediment were collected from a freshwater habitat. Two Winogradsky columns were constructed and allowed to develop: a classical Winogradsky column incubated in the light at room temperature (Fig. 2A) and a Winogradsky column incubated in the dark at room temperature (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2B: A photo of classical Winogradsky column (left), incubated at room temperature in light for 68 days and a Winogradsky column incubated at room temperature in the dark for 68 days (right).

After allowing the columns to develop for 7-9 weeks, the layers in the classical column can be compared to the column incubated in the dark (Fig. 2B). In the classical Winogradsky column, a green cyanobacterial layer can be observed near the top of the tube. Near the center of the tube, a red-purple layer can be observed, indicative of purple nonsulfur bacteria. Under this layer, a purple-red layer is observed, indicative of purple sulfur bacteria. Directly under this layer, black sediment can be observed in the anaerobic region of the column, indicative of sulfate reducing bacteria.

The column grown in the dark (Fig. 2B) developed differently than the classical Winogradsky column. Like the classical column, the dark column yielded black sediment near the bottom of the column, indicative of sulfate reducing bacteria. The dark column did not yield the green cyanobacterial layer, nor the red, purple, or green layers indicative of purple nonsulfur, purple sulfur, and green sulfur bacteria, respectively. These groups are dependent on light for growth, and therefore unable to grow in the dark.

The precise results of each Winogradsky column will vary widely with their incubation conditions and their source habitats.

Microbial communities originating from freshwater habitats will not be accustomed to high salt concentrations and the addition of salt may slow down or inhibit growth. Conversely, there may be sufficient halophilic bacteria in brackish and saltwater habitats so that the addition of salts makes no difference or even enhances the growth of particular layers when compared to a column without added salts.

Sandy sediments are more porous than muddy sediments. If enough sulfide is produced in such porous sediments, sulfides can diffuse all the way to the top of the column and inhibit growth of aerobic organisms. In this case, the column may only contain layers indicative of anaerobes and may not contain any aerobes, such as the cyanobacteria.

Freshwater generally contains less sulfate than saltwater. Sulfate is important for the growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Sulfate reducers create sulfide as a byproduct and are indicated by the development of a black layer in the bottom of the column. If sulfate is not supplemented to freshwater communities, sulfate reducers may not produce enough sulfide. The creation of the sulfide byproduct is important for the growth of green and purple sulfur bacteria and the nonphotosynthetic sulfur oxidizers. In these cases, sulfur oxidizers can still grow using the egg yolk as a source of sulfur, even if the sulfate reducers (black layer) never develop.

Different wavelengths of light should select for organisms with different absorption pigments. A column kept in the dark will only allow for nonphotosynthetic organisms to grow, including sulfate reducers, iron oxidizers, and methanogens. Photosynthesizers have pigments that absorb light at different wavelengths within the visible range (~400-700nm). By covering a column with, for example, blue cellophane, blue light (~450-490nm) is blocked from entering the column. All of the photosynthesizers in the column have pigments which require the blue wavelengths (6) and their growth should be inhibited. On the other hand, red cellophane will block light of ~635-700nm. These wavelengths are important for the pigments used by cyanobacteria (6), while purple sulfur, green sulfur, and purple nonsulfur bacteria may still be able to grow.

Different microbial communities may have vastly different adaptive abilities to cope with changes in temperatures. High temperatures can enhance rates of microbial activity when sufficient thermophiles are present. On the other hand, in the absence of thermophiles, high temperatures may decrease overall microbial activity. Similarly, low temperatures may decrease overall microbial activity unless the microbial community contains sufficient psychrophiles.

Applications and Summary

The Winogradsky column is an example of an interdependent microbial ecosystem. After mixing mud, water, and additional carbon and sulfur substrates in a vertical column, the stratified ecosystem should stabilize into separate, stable zones over several weeks. These zones are occupied by different microorganisms which flourish at a particular spot along the gradient between the sulfide-rich sediment in the bottom and the oxygen-rich sediment at the top. By manipulating the conditions and substrates within the Winogradsky column, the presence and activity of different microorganisms such as halophiles, thermophiles, psychrophiles, sulfur oxidizers, sulfur reducers, iron oxidizers, and photosynthesizers can be observed.

References

- Zavarzin G. (2006). Winogradsky and modern microbiology. Microbiology 75(6): 501-511. doi: 10.1134/s0026261706050018

- Esteban DJ, Hysa B, and Bartow-McKenney C (2015). Temporal and Spatial Distribution of the Microbial Community of Winogradsky Columns. PLoS ONE 10(8): e0134588. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134588

- Lloyd KG, Steen AD, Ladau J, Yin J, and Crosby L. (2018). Phylogenetically novel uncultured microbial cells dominate Earth microbiomes. mSystems 3(5): e00055-18. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00055-18

- Anderson DC, and Hairston RV (1999). The Winogradsky Column & Biofilms: Models for Teaching Nutrient Cycling & Succession in an Ecosystem. The American Biology Teacher, 61(6): 453-459. doi: 10.2307/4450728

- Dang H, Klotz MG, Lovell CR and Sievert SM (2019) Editorial: The Responses of Marine Microorganisms, Communities and Ecofunctions to Environmental Gradients. Frontiers in Microbiology 10(115). doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00115

- Stomp M, Huisman J, Stal LJ, and Matthijs HCP. (2007) Colorful niches of phototrophic microorganisms shaped by vibrations of the water molecule. ISME Journal. 1(4): 271-282. doi:10.1038/ismej.2007.59

- Perry JJ, Staley JT, and Lory S. (2002) Microbial Life, First Edition, published by Sinauer Associates

- Rogan B, Lemke M, Levandowsky M, and Gorrel T. (2005) Exploring the Sulfur Nutrient Cycle Using the Winogradsky Column. The American Biology Teacher, 67(6): 348-356. doi: 10.2307/4451860

Transcript

Most of the Earth’s microorganisms cannot be cultured in a lab, often because they rely on other microbes within their native communities. A Winogradsky column, named for its inventor Sergei Winogradsky, is a miniature, enclosed ecosystem which enriches the microbial communities within a sediment sample, enabling scientists to study many of the microbes that play a vital role in Earth’s biogeochemical processes, without needing to isolate and culture them individually.

Typically, mud and water from an ecosystem, such as a pond or a marsh, are mixed. As an optional experiment, salt can be added to this mixture to enrich various halophile species. Next, a small portion of the mixture is supplemented with carbon, usually in the form of cellulose from newspaper, and sulfur, usually from an egg yolk. For another optional experiment, a nail can be added to this mixture to enrich certain Gallionella species. This new mixture is then added to a transparent column, so that the column is one quarter full. Finally, the rest of the mud mixture and more water is added to the column until it is most of the way full.

Succession, which refers to the consecutive development of different microbial communities over time, can be observed in real time with a Winogradsky column. As microbes grow within the column, they consume specific substrates and change the chemistry of their environment. When their substrates are depleted, the original microbes die off and microbes with different metabolic needs can flourish in the altered environment. Over time, visibly distinct layers begin to form, each containing parts of a bacterial community with different microenvironmental needs.

For example, photosynthetic microbes, largely composed of cyanobacteria, form green or red-brown layers near the top of the column. Since photosynthesis produces oxygen, often seen as bubbles in the top portion of the column, a gradient is formed with the highest oxygen concentrations near the top, and the lowest towards the bottom. Depending upon the available substrates, different microbial communities can grow in the anaerobic bottom layer. Bubbles in this layer can indicate the presence of methanogens, which create methane gas via fermentation. Here, the microbial fermentation of cellulose results in organic acids. Sulfate reducers oxidize those acids to produce sulfide, and their activity is indicated by black sediment. Sulfide diffuses upward in the column, creating yet another gradient where sulfide concentrations are highest towards the bottom of the column, and lowest near the top. Towards the middle of the column, sulfur oxidizers utilize the oxygen from above and sulfide from below. With adequate light, photosynthetic sulfur oxidizers, such as green and purple sulfur bacteria, develop. Green sulfur bacteria tolerate higher sulfide concentrations. Thus, they grow directly below the purple sulfur bacteria. Directly above this layer, purple non-sulfur bacteria form a red-orange layer. Nonphotosynthetic sulfur oxidizers are indicated by the presence of white filaments.

Conditions such as light and temperature can also be varied to enrich other communities. In this video, you will learn how to construct a Winogradsky column, and vary the growing conditions and substrates to enrich specific microbial communities.

First, locate an appropriate aquatic ecosystem, such as a pond or marsh. The sediment samples should come from the area near the water’s edge, and be completely saturated with water. Then, use a shovel and a bucket to collect one to two liters of the saturated mud. Next, obtain approximately three liters of fresh water from the same source and return to the lab with the field samples.

In the lab, put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves. Now, transfer approximately 750 milliliters of mud to a mixing bowl. Then, sift through the mud to remove large rocks, twigs, or leaves and use a spoon to break apart any clumps. Next, add some of the fresh water to the mixing bowl, and stir with a large spoon. Add water until the consistency of the water-mud mixture is similar to a milkshake. Continue to make sure there are no clumps.

As an optional experiment, select for halophilic bacteria by adding 25 to 50 milligrams of salt to the mud mixture.

Then, transfer approximately 1/3 of the water-mud mixture to a second mixing bowl. Add one egg yolk and a handful of shredded newspaper to the bowl. Next, add this mixture to the column, until it is about 1/4 full. Next, add the water-mud mixture without the egg and newspaper to the column, until it is approximately 3/4 full. Then, add more water to the column, leaving a 1/2 inch space on top. Cover the column with plastic wrap and secure it with a rubber band.

Incubate the column in the light near a window at room temperature for the next four to eight weeks. Throughout the incubation period, monitor changes in the Winogradsky column at least once a week for the development of different colored layers and the formation of bubbles. Additionally, record the time it takes for different layers to develop.

Another modification that can be done is incubating the column near a radiator to select for thermophilic bacteria, or in a refrigerator to select for psychrophilic bacteria. Vary the light conditions by placing different columns in high light, low light, or darkness to incubate. Alternatively, limit the wavelength of incoming light by covering the column with different shades of cellophane to determine which colors select for different bacterial groups. For another optional experiment, to enrich iron-oxidizing bacteria, add a nail to the mud-water mixture prior to the addition of newspaper and an egg yolk.

After one to two weeks, growth of the cyanobacterial layer is indicated by a green or red-brown film on top of the mud layer of the classical Winogradsky column. Over time, the appearance and evolution of the different layers is monitored, each indicative of the different types of bacteria present. When comparing a column grown in the dark to a traditional Winogradsky column, we see the dark treatment yields the black layer at the bottom of the column, indicative of sulfate-reducing bacteria.

The dark column may also yield other layers, depending on other incubation conditions. Additionally, the dark column doesn’t yield the green cyanobacterial layer, nor the red, purple, or green layers indicative of purple non-sulfur, purple sulfur, and green sulfur bacteria respectively. These groups are dependent on light for growth.