Conjugación: Un método para transferir resistencia a ampicilina de un donante a una E. Coli receptora

English

Share

Overview

Fuente: Alexander S. Gold1, Tonya M. Colpitts1

1 Departamento de Microbiología, Escuela de Medicina de la Universidad de Boston, Laboratorios Nacionales de Enfermedades de Infecciones Emergentes, Boston, MA

Descubierto por primera vez por Lederberg y Tatum en 1946, la conjugación es una forma de transferencia de genes horizontal entre bacterias que se basa en el contacto físico directo entre dos células bacterianas (1). A diferencia de otras formas de transferencia de genes, como la transformación o la transducción, la conjugación es un proceso natural en el que el ADN se secreta de una célula donante a una célula receptora de manera unidireccional. Esta direccionalidad y la capacidad de este proceso para aumentar la diversidad genética de las bacterias ha dado a la conjugación la reputación como una forma de “mate” bacteriano, que se cree que ha contribuido en gran medida al reciente aumento de los antibióticos resistentes bacterias (2, 3). Mediante el uso de presiones selectivas, por ejemplo el uso de antibióticos, la conjugación ha sido manipulada para su uso en el entorno de laboratorio, lo que la convierte en una poderosa herramienta para la transferencia horizontal de genes entre bacterias, y en algunos casos de bacterias a levaduras, plantas y animales células (4). Aparte de las aplicaciones en el laboratorio, la transferencia del gen de la bacteria-eucariota por conjugación es una emocionante vía de transferencia de ADN con una multitud de posibles aplicaciones biotécnicas e implicaciones naturales (5).

Se cree que la conjugación funciona mediante un “mecanismo de dos pasos” (6). En primer lugar, antes de que se pueda transferir cualquier ADN, la célula donante debe hacer contacto directo de célula a célula con el receptor. Este proceso se ha caracterizado mejor en bacterias gramnegativas, la más estudiada de las cuales es Escherichia coli. El contacto célula a célula se establece mediante la presencia de una compleja red de filamentos extracelulares en el donante conocido como sex pilus, un elemento conjugado codificado por el gen transferible conocido como factor F (fertilidad) (7, 8). Además de establecer el contacto entre el donante y el receptor, varias proteínas se transportan a través del pilus sexual al citoplasma receptor, formando un conducto del sistema de secreción tipo IV (T4SS) entre las dos células, una estructura necesaria para el segundo paso de conjugación, transferencia de ADN (6). Al combinar esta función del sex pilus con la replicación del círculo rodante del ADN, la célula donante es capaz de transferir ADN en forma de un elemento transposable, como un plásmido o transposón, al receptor mediante un modelo de “disparo y bomba” (6). En este caso, el “disparo” es el transporte de la proteína piloto, con ADN vinculado, por el T4SS a la célula receptora, y el “bomba” es el transporte activo de ADN al receptor, un proceso que depende del T4SS y catalizado por el acoplamiento de proteínas (6). La maquinaria utilizada en este proceso se compone de un origen de la secuencia de transferencia (oriT), que debe ser proporcionada por el ADN en cis y genes trans, que codifican una relaxasa, complejo de formación de pares de parejas, y proteína de acoplamiento tipo IV, y puede estar presente en cis o trans (9). Esta relajara corta el sitio nic dentro de la secuencia de oriT y se une covalentemente al extremo de 5′ de la hebra transferida para producir el relajante, un complejo de ADN-relaxasa de una sola cadena con otras proteínas auxiliares (9). Una vez formado, el relajantese se conecta al complejo de formación del par de apareamiento, a través de la proteína de acoplamiento tipo IV, que permite la transferencia del complejo ssDNA-relaxasa a las células receptoras por el T4SS (10). Una vez en el citoplasma del receptor, el ADN puede integrarse en el genoma del receptor o existir por separado en forma de plásmido, cualquiera de los cuales permite la expresión de sus genes.

En este experimento, se utilizó la cepa de donante de conjugación ampliamente utilizada E. coli WM3064 para transferir la codificación genética para la resistencia a la ampicilina a la cepa receptora E. coli J53. Mientras que ambas cepas de las bacterias gramnegativas eran resistentes a la tetraciclina, sólo la cepa de donante WM3064 tenía el gen de la resistencia a la ampicilina, codificado en el vector de transbordador pWD2-oriT, y era auxotrópico al ácido diaminopimélico (DAP) (11-13). Este experimento consistió en dos pasos principales, la preparación de cepas de donantes y receptores, seguido según la transferencia del gen de resistencia a la ampicilina del donante al receptor por conjugación (Figura 1).

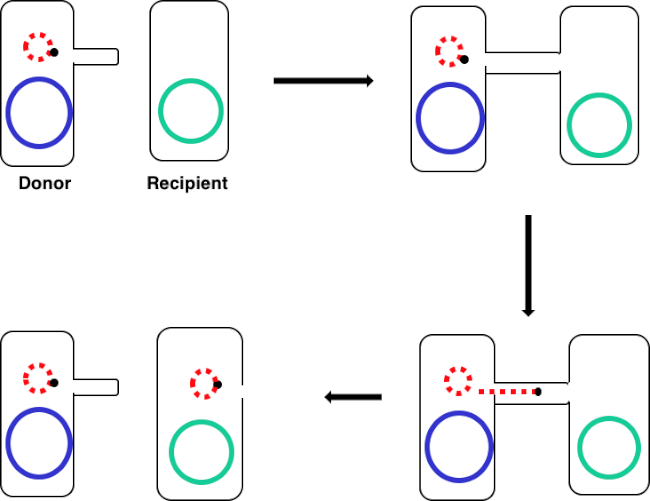

Figura 1: Esquema de conjugación. Este esquema muestra la transferencia exitosa de un plásmido, solo un ejemplo de un elemento de ADN transposable, de una célula donante a una célula receptora mediante conjugación. Tras el contacto con la célula receptora por la célula donante a través del sex pilus, el plásmido se replica mediante la replicación del círculo rodante, se mueve a través del complejo multiproteico que une las dos células y forma un nuevo plásmido de longitud completa en la célula receptora.

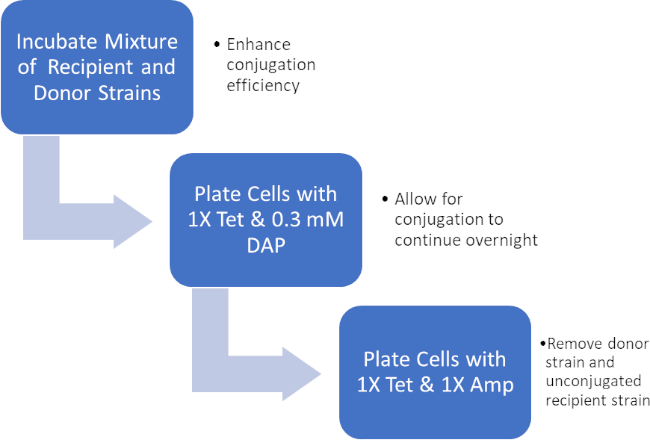

Al incubar una mezcla de células receptoras y donantes, y luego enchapar sucesivamente estas células en presencia de tetraciclina y DAP, esto permitió la transferencia exitosa del gen de resistencia a la ampicilina. Sucesivamente células de chapado cultivadas a partir de esta mezcla en presencia de tetraciclina y ampicilina, eliminaron todas las células del donante debido a la falta de DAP y cualquier célula receptora que no haya obtenido el gen de resistencia a la ampicilina, produciendo una cepa J53 estrictamente receptora bacterias que adquirieron resistencia a la ampicilina (Figura 2). Una vez realizada, la transferencia exitosa del gen de resistencia a la ampicilina fue confirmada por PCR. Dado que la conjugación tuvo éxito, la cepa J53 de E. coli contenía pWD2-oriT y era resistente a la ampicilina, y la codificación genética para esta resistencia es detectable por PCR. Sin embargo, de no tener éxito no habría habido detección del gen de resistencia a la ampicilina y la ampicilina seguiría funcionando como un antibiótico eficaz contra la cepa J53.

Figura 2: Esquema de protocolo. Este esquema muestra una visión general del protocolo presentado.

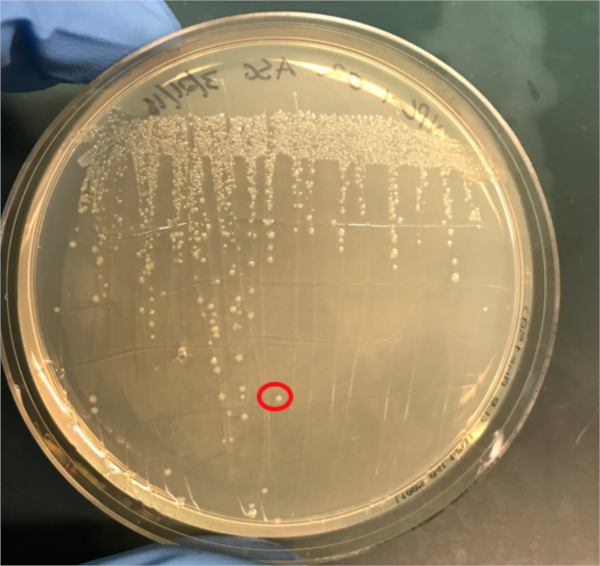

Figura 3A: La confirmación de la conjugación exitosa por PCR. A) Las existencias de congelador de las muestras de control conjugadas y negativas fueron rayadas en placas de agar y se seleccionó una colonia (roja) para el aislamiento del ADN.

Procedure

Results

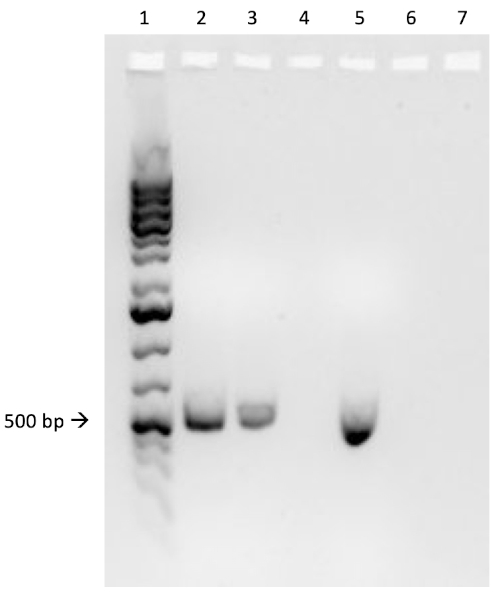

If conjugation was successful, a 500 base-pair sized band PCR product will be observed in the well in which PCR reaction 1 was loaded (Well #2 in Figure 3B), while no bands will be observed in the well in which PCR reaction 3 was loaded (Well #4 in Figure 3B). The presence of this band confirms the successful transfer of the ampicillin resistance gene, thereby conferring ampicillin resistance to the J53 strain of E. coli.

Figure 3B: The confirmation of successful conjugation by PCR. B) PCR analysis was done using DNA isolated from the select colony. The contents of each well are as follows: 1) DNA ladder, 2) Conjugation DNA and ampicillin primers, 3) Conjugation DNA and housekeeping primers, 4) Negative control DNA and ampicillin primers, 5) Negative control DNA and housekeeping primers, 6) No DNA and ampicillin primers, and 7) No DNA and negative control primers. The presence of a ~ 500 base-pair band PCR product from PCR reaction 1 (well 2), and the lack of this product from PCR reaction 3 (well 4), confirms successful conjugation.

Applications and Summary

Conjugation is a naturally occurring process of horizontal gene transfer that relies on the direct cell-to-cell contact of a donor cell and a recipient cell. This process is shared among all kinds of bacteria and has been instrumental in bacterial evolution, most notably antibiotic resistance. In the lab, conjugation can be used as an effective method of gene transfer that is much less disruptive when compared to other techniques. Outside of the laboratory, the ability to transfer DNA from bacteria to eukaryotes via conjugation offers an exciting new avenue of gene therapy and understanding the implications of these naturally occurring gene transfers, for example the relationship between bacterial infection and cancer, is a rapidly emerging area of research.

References

- Lederberg J, Tatum, E.L. Gene recombination in Escherichia coli Nature. 1946;158:558.

- Holmes R.K. J, M.G. Genetics: Exchange of Genetic Information. 4th Edition ed. Baron S, editor. Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996.

- Cruz F, Davies, J. Horizontal gene transfer and the origin of species: lessons from bacteria. Trends in Microbiology. 2000;8:128-33.

- Llosa M, Cruz, F. Bacterial conjugation: a potential tool for genomic engineering. Ressearch in Microbiology. 2005;156:1-6.

- Lacroix B, Citovsky, V. Transfer of DNA from Bacteria to Eukaryotes. mBio. 2016;7(4):1-9.

- Llosa M, et al. Bacterial conjugation: a two-step mechanism for

- DNA transport. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;45:1-8.

- Grohmann E, Muth, G., Espinosa, M. Conjugative Plasmid Transfer in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2003;67:277-301.

- Firth N, Ippen-Ihler, K, Skurray, RA. Structure and function of the F factor and mechanism of conjugation. Escherichia coli and salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 1996;2:2377-401.

- Smillie C, Garcillan-Barcia MP, Francia MV, Rocha EPC, De La Cruz F. Mobility of Plasmids. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2010;74(3):434-52.

- Cascales E. Definition of a Bacterial Type IV Secretion Pathway for a DNA Substrate. 2004;304(5674):1170-3.

- Wang P, Yu Z, Li B, Cai X, Zeng Z, Chen X, et al. Development of an efficient conjugation-based genetic manipulation system for Pseudoalteromonas. Microbial Cell Factories. 2015;14(1):11.

- Yi H, Cho YJ, Yong D, Chun J. Genome Sequence of Escherichia coli J53, a Reference Strain for Genetic Studies. Journal of Bacteriology. 2012;194(14):3742-3.

- Baumann RLB, E. H.; Wiseman, J. S.; Vaal, M.; Nichols, J. S. Inhibition of Escherichia coli Growth and Diaminopimelic Acid Epimerase by 3-Chlorodiaminopimelic Acid. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 1988;32:1119-23.

- Rocha D, Santos, CS, Pacheco LG. Bacterial reference genes for gene expression studies by RT-qPCR: survey and analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2015;108:685-93.

Transcript

Bacterial cells, such as E. coli, are able to transfer genetic information from cell-to-cell. Conjugation differs from other mechanisms of DNA transfer, such as transduction or transformation, in that it requires physical contact between the cells.

To proceed, conjugation requires a donor cell that expresses the fertility, or F, factor and a recipient cell without it, an F minus cell. The process requires two steps. The first is the establishment of direct cell-to-cell contact. To do this, the donor cell generates an extracellular filamentous structure called a sex pilus. It is named this since conjugation is a form of mating for asexually reproducing bacteria, but it should be noted that it is not true sexual reproduction as no gametes are exchanged and no offspring are formed.

The second step is delivery of DNA to the recipient cell. After the sex pilus establishes contact between two cells, a conduit called the Type IV secretion system is built allowing for the transfer of DNA. The donor cell then begins to replicate the extrachromosomal DNA that will be transferred selected based on the presence of a genetic element known as the OriT or origin of transfer. One end of the newly replicated DNA is threaded into the conduit through DNA protein binding. As the DNA is further replicated, it is pumped through the channel, facilitated by a complex of proteins encoded by genes located close to the OriT. Once the DNA is fully transferred, it will either form an extra chromosomal plasmid, or it may integrate into the chromosome of the recipient cell. Whichever the endpoint of the transferred DNA, the genes it encodes will then be expressed. This gene expression can be used to confirm successful conjugation.

For example, consider a scenario where the donor strain expresses ampicillin resistance and passes this on in the conjugated DNA to the recipient bacterium, but the recipient strain also has a tetracycline resistance gene not present in the donor. In this event, when the cells are plated on LB media containing both tetracycline and ampicillin, colonies should grow only from successfully conjugated bacteria, which will be expressing both resistance phenotypes. To further confirm successful conjugation, plasmid DNA from these colonies can be harvested and then a section of DNA specific to the transferred plasmid can be amplified using polymerase chain reaction, or PCR. When the PCR product is run on an electrophoresis gel alongside a ladder of standard sizes, a PCR fragment of a known size should be visible on the gel, further confirming successful conjugation. In this experiment, a plasmid will be used to transfer the ampicillin resistance gene via conjugation from a donor strain to a tetracycline-resistant recipient strain. After this, to confirm conjugation, the conjugation mixture will be incubated on a plate containing both antibiotics leaving only the transformed bacteria. Finally, successful conjugation will be further confirmed with PCR.

Before starting the procedure, put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves. Next, sterilize the workspace using 70% ethanol to wipe down the surface.

In this procedure, the ampicillin resistance gene will be transferred from the WM3064 strain of E. coli to the J53 strain of E. coli via conjugation. The donor strain WM3064 is resistant to tetracycline and ampicillin and it requires diaminopimelic acid, or DAP, to grow. The recipient strain J53 is only resistant to tetracycline and it does not require DAP to grow. This means that successfully conjugated cells should be resistant to tetracycline and ampicillin and can grow without DAP.

Prepare the donor strain culture by inoculating five milliliters of LB containing 0.3 millimoles of DAP with a scrap of the frozen donor strain glycerol stock. Then, prepare the recipient strain by inoculating five milliliters of LB broth without DAP with a scrap of the frozen recipient strain glycerol stock. Grow these cultures overnight at 37 degrees Celsius with aeration and shaking at 220 RPM in a shaking incubator. Once the cultures have grown to an OD 600 of two, remove one milliliter of culture from each and place this into two new separate 1.5 milliliter microcentrifuge tubes. Then, centrifuge these aliquots at 3000 RPM for five minutes to pellet the bacterial cells. Discard the supernatant and wash each pellet with 250 microliters of 1X PBS. Centrifuge the samples again and, after discarding the supernatant, resuspend each pellet in 500 microliters of PBS.

To begin the conjugation procedure, first combine 50 microliters of recipient cells with 50 microliters of donor cells in a 1.5 milliliter microcentrifuge tube and mix by pipetting up and down gently. Next, pipette 100 microliters of the recipient cell culture onto another 1X tetracycline plate containing DAP. Next, prepare your negative control by pipetting 100 microliters of the recipient cell culture only onto a non-selective agar plate containing DAP. Then, incubate the conjugation and negative control plates overnight at 37 degrees Celsius.

The next day, take a sterile cell scraper and harvest cells from the conjugation plate by collecting colonies. Then, transfer the colonies to a sterile 1.5 milliliter microcentrifuge tube containing one milliliter of 1X PBS. Repeat this process to collect the recipient cells from the other plate.

After this, vortex the samples to mix. After mixing, transfer the tubes to a centrifuge to gently pellet the cells. Discard the supernatant, then wash the cell pellets in one milliliter of PBS and vortex the tubes to resuspend the cells. Pellet the cells again by centrifuging. Discard the supernatant again and resuspend both cell pellets in one milliliter of PBS. Now, using a sterile pipette tip, plate 100 microliters of the conjugation reaction cell mixture onto an LB agar plate without DAP containing 1X tetracycline and 1X ampicillin. Repeat the plating method using 100 microliters of a ten-fold dilution of the same cell mixture in PBS onto another LB agar plate without DAP containing 1X tetracycline and 1X ampicillin.

Finally, pipette 100 microliters of the negative control cell mixture onto a single LB agar plate with 1X tetracycline only. After overnight incubation at 37 degrees Celsius, the colonies should be visible. Using a sterile pipette tip, pick a single colony from the conjugation reaction plate and add it to a tube containing five milliliters of selective LB media containing both antibiotics. Then, repeat the colony isolation by selecting a single colony from the recipient cell plate. Grow these cultures overnight at 37 degrees Celsius with aeration at 220 RPM.

The next day, wipe down the bench top with 70% ethanol and remove the plates from the incubator. Use a DNA mini prep kit to isolate DNA from 4. 5 milliliters of each culture according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After completing the DNA mini prep, elute the DNA using 35 microliters of nuclease-free water. Finally, use the remaining 0. 5 milliliters of each culture to prepare one milliliter glycerol stocks by adding 0.5 milliliters of 100% glycerol for a one-to-one dilution. Place these aliquots at minus 80 degrees Celsius for storage until needed.

To confirm successful conjugation by PCR, first prepare a PCR master mix by adding 75 microliters of 2X PCR master mix to a microcentrifuge tube. Then, add 7.5 microliters each of a 10 micromolar forward primer and a 10 micromolar reverse primer designed to amplify the ampicillin resistance gene from the plasmid. Next, prepare a second PCR master mix by adding 75 microliters of 2X PCR master mix to a microcentrifuge tube and then adding 7.5 microliters each of a 10 micromolar forward primer and 10 micromolar reverse primer designed to amplify a housekeeping gene, in this case DNA gyrase B.

Now, add 15 microliters of the first master mix to a PCR tube and then add 10 nanograms, approximately two microliters of the template experimental DNA to the same tube. Bring the reaction up to a final volume of 25 microliters with nuclease-free water. Repeat these steps to produce the remaining five reactions, so that the tubes contain the components shown here. Now, transfer these reactions to a thermocycler with the block pre-heated to 98 degrees Celsius and then initiate the program. After completion of the PCR, remove the tubes from the machine. Then, load two microliters of each reaction mixed with two microliters of loading dye and four microliters of a molecular weight marker into consecutive wells of a 1% agarose gel. Set the gel to run at 150 volts for 20 minutes. Finally, visualize the gel using a UV illuminator.

In this experiment, the successful transfer of the ampicillin resistance gene via conjugation was confirmed via PCR. Here, a roughly 500 base pair sized band should be observed in the well containing the conjugated DNA and ampicillin primers, well two in this example. A housekeeping gene, DNA gyrase B, was loaded into wells three and five with conjugated DNA and recipient cell DNA, respectively. Bands observed in these wells act as a positive control to ensure the DNA template was present and that PCR was successful. Bands should not be observed in the well containing the reaction for recipient cell DNA and the ampicillin primer pair, well four in this example, because the recipient cells are not ampicillin-resistant. Additionally, no bands should be observed in the reactions lacking template DNA, wells six and seven here. If these conditions are met, this will confirm the successful transfer of the ampicillin resistance gene, conferring ampicillin resistance from the WM3064 strain of E. coli to the J53 strain of E. coli.