使用场效应生物传感技术探索分子伴侣Hsp90与其客户蛋白激酶Cdc37之间的生物分子相互作用

Summary

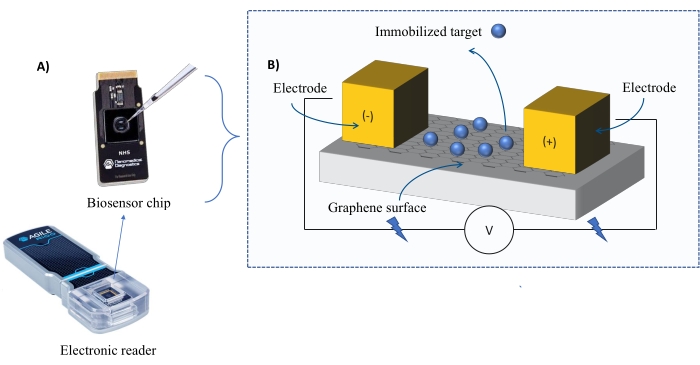

场效应生物传感(FEB)是一种用于检测生物分子相互作用的无标记技术。它测量通过石墨烯生物传感器的电流,结合目标被固定到该传感器。FEB技术用于评估Hsp90和Cdc37之间的生物分子相互作用,并检测到两种蛋白质之间的强相互作用。

Abstract

生物分子相互作用通过调节和协调功能相关的生物事件,在众多细胞过程中发挥多种作用。蛋白质,碳水化合物,维生素,脂肪酸,核酸和酶等生物分子是生物的基本组成部分;它们组装成生物系统中的复杂网络,以同步无数的生活事件。蛋白质通常利用复杂的相互作用组网络来执行其功能;因此,必须评估这种相互作用,以揭示它们在细胞和生物体水平上在细胞中的重要性。为了实现这一目标,我们引入了一种快速新兴的技术,场效应生物传感(FEB),以确定特定的生物分子相互作用。FEB是一种台式,无标记且可靠的生物分子检测技术,用于确定特定的相互作用,并使用高质量的电子生物传感器。FEB技术可以监测纳米摩尔范围内的相互作用,因为其生物传感器表面使用了生物相容性纳米材料。作为概念验证,阐明了热休克蛋白90(Hsp90)和细胞分裂周期37(Cdc37)之间的蛋白质 – 蛋白质相互作用(PPI)。Hsp90是一种ATP依赖性分子伴侣,在许多蛋白质的折叠,稳定性,成熟和质量控制中起着至关重要的作用,从而调节多种重要的细胞功能。Cdc37被认为是一种蛋白激酶特异性分子伴侣,因为它特异性识别并招募蛋白激酶到Hsp90以调节其下游信号转导途径。因此,Cdc37被认为是Hsp90的共同伴侣。伴侣激酶途径(Hsp90 / Cdc37复合物)在促进细胞生长的多种恶性肿瘤中被过度激活;因此,它是癌症治疗的潜在靶点。本研究证明了使用Hsp90/Cdc37模型系统的FEB技术的有效性。FEB检测到两种蛋白质之间的PPI很强(在三个独立实验中KD 值为0.014μM,0.053μM和0.072μM)。总之,FEB是一个无标签且具有成本效益的PPI检测平台,可提供快速准确的测量。

Introduction

生物分子相互作用:

蛋白质是生物体的重要组成部分,参与许多分子途径,如细胞代谢,细胞结构,细胞信号传导,免疫反应,细胞粘附等。虽然一些蛋白质独立执行其功能,但大多数蛋白质使用结合界面与其他蛋白质相互作用以协调适当的生物活性1。

生物分子相互作用可以主要根据所涉及的蛋白质2的独特结构和功能特征进行分类,例如,基于蛋白质表面的复合物稳定性或相互作用的持久性3。鉴定必需蛋白质及其在生物分子相互作用中的作用对于在分子水平4上理解生化机制至关重要。目前,有各种方法来检测这些相互作用5:体外6, 计算机7,活细胞8,离体9和 体内10,每种方法都有自己的优点和缺点。

使用整个动物作为实验工具11进行体内测定,并且通过在自然条件下提供最小的改变,在受控的外部环境中对组织提取物或整个器官(例如,心脏,大脑,肝脏)进行离体测定。体内和离体研究最常见的应用是通过确保其整体安全性和有效性,在人体试验之前评估潜在药理学药物的药代动力学,药效学和毒性作用12。

生物分子相互作用也可以在活细胞内检测到。成像活细胞使我们能够观察动态相互作用,因为它们执行特定生化途径13的反应。此外,检测技术,例如生物发光或荧光共振能量转移,可以提供关于这些相互作用在细胞14内何时何地发生的信息。虽然活细胞中的检测提供了关键的细节,但这些检测方法依赖于光学和标记,这可能不反映本地生物学;它们也比 体外 方法控制得更少,并且需要专业知识来执行15。

计算机计算方法主要用于在体外实验之前对目标分子进行大规模筛选。计算预测方法,基于计算机的数据库,分子对接,定量构效关系和其他分子动力学模拟方法是计算机工具16中公认的方法。与费力的实验技术相比,计算机计算机工具可以轻松做出高灵敏度的预测,但预测性能的准确性会降低17.

体外 测定是使用其标准生物背景之外的微生物或生物分子进行的。通过 体外 方法描绘生物分子相互作用对于理解蛋白质功能和复杂细胞功能网络背后的生物学至关重要。优选的测定方法根据蛋白质的内在性质,动力学值以及相互作用的模式和强度18,19选择。

Hsp90/Cdc37 相互作用:

连接Hsp90和Cdc37的伴侣激酶途径是肿瘤生物学20中一个有前途的治疗靶点。Hsp90在细胞周期控制,蛋白质组装,细胞存活和信号通路中起着核心作用。依赖Hsp90进行功能的蛋白质通过共同伴侣(如Cdc37)递送到Hsp90进行复合。Hsp90 / Cdc37复合物控制大多数蛋白激酶的折叠,并作为众多细胞内信号网络的枢纽21。它是一种有前途的抗肿瘤靶点,因为它在各种恶性肿瘤(包括急性成骨髓细胞白血病,多发性骨髓瘤和肝细胞癌22,23)中的表达升高。

常用 的体外 生物分子相互作用检测技术

共免疫沉淀(co-IP)是一种依靠抗原- 抗体特异性来鉴定生物学相关相互作用的技术24。该方法的主要缺点是它无法检测低亲和力相互作用和动力学值24。等温滴定量热法 (ITC)、表面等离子体共振 (SPR)、生物层干涉测量 (BLI) 和 FEB 技术等生物物理方法优先用于确定动力学值。

ITC是一种基于结合能测定以及完整的热力学分析的生物物理检测方法,用于表征生物分子相互作用25。ITC的主要优点是它不需要对靶蛋白进行任何标记或固定。ITC遇到的主要困难是一个实验所需的高浓度靶蛋白以及由于小结合焓26而难以分析非共价复合物。SPR和BLI都是无标记的生物物理技术,依赖于目标分子在传感器表面上的固定化,然后在固定的靶标27,28上随后注入分析物。在SPR中,测量生物分子相互作用期间折射率的变化27;在BLI中,反射光中的干涉被实时记录为波长的变化,作为时间28的函数。SPR 和 BLI 在提供高特异性、灵敏度和检测能力方面具有共同的优势29.在这两种方法中,靶蛋白固定在生物传感器表面上,因此,靶标的天然构象可能存在一些损失,这使得难以区分特异性与非特异性相互作用30。BLI使用昂贵的一次性光纤生物传感器来固定目标,因此是一种昂贵的技术31。与这些成熟的生物分子检测工具相比,FEB技术通过使用低纳摩尔浓度进行生物分子实时检测和动力学表征,提供了一个可靠且无标记的平台。FEB技术还克服了ITC面临的冒泡挑战,与SPR或BLI相比更具成本效益。

基于场效应晶体管(FET)的生物传感器是通过提供各种生物医学应用来检测生物分子相互作用的新兴领域。在FET系统中,目标被固定在生物传感器芯片上,并且通过电导32的变化来检测相互作用。在开发高效电子生物传感器时要考虑的独特特征是物理化学性质,例如用于制造传感器表面33的涂层材料的半导体性质和化学稳定性。传统的材料,如用于FET的硅已经限制了传感器的灵敏度,因为它需要夹在晶体管通道和特定环境之间的氧化物层34。此外,硅晶体管对高盐环境敏感,因此很难测量其自然环境中的生物相互作用。基于石墨烯的生物传感器作为替代品提供,因为它具有出色的化学稳定性和电场。由于石墨烯是碳的单原子层,因此它作为半导体非常敏感,并且与生物溶液具有化学相容性;这两种质量都是期望生成兼容的电子生物传感器35。石墨烯包覆生物传感器提供的生物分子的超高负载潜力导致基于石墨烯的生物传感器FEB技术的发展。

FEB技术原理:FEB是一种无标记的生物分子检测技术,可测量通过石墨烯生物传感器的电流,结合目标被固定到石墨烯生物传感器。固定化蛋白质与分析物之间的相互作用导致实时监测的电流变化,从而实现准确的动力学测量36。

仪器仪表:FEB系统包括一个石墨烯场效应晶体管(gFET)传感器芯片和一个在整个实验中施加恒定电压的电子阅读器(图1)。将分析物在溶液中施加到固定在生物传感器表面上的靶蛋白上。当相互作用发生时,实时测量和记录电流的变化。随着分析物浓度的增加,结合分析物的比例也会增加,导致电流中的更高交替。使用仪器随附的自动分析软件(材料表),以生物传感单元(BU)37测量和记录I-Response。I-Response被定义为在固定目标与分析物相互作用时实时测量的通过生物传感器芯片的电流(I)的变化。FEB自动分析软件可以分析I响应和C响应动态相互作用事件,其中C响应记录电容(C)的变化。I-Response和C-Response的变化直接对应于结合分析物的分数,并且可以进一步分析以产生KD 值。自动分析软件的默认首选项为 I-响应。

图1:实验设置概述,(A)基于石墨烯的芯片和电子阅读器。(B)芯片组件概述。芯片连接到两个电极上,为系统提供电流。芯片的表面覆盖着石墨烯,石墨烯在被激活时可以结合目标。请点击此处查看此图的大图。

方法论:

最初,将激活的生物传感器芯片插入FEB器件(图1),然后执行下面概述的步骤:(1)校准:实验开始于使用1x磷酸盐缓冲盐水(PBS;pH = 7.4)进行系统校准,以产生基线平衡响应。(2)关联:将分析物引入芯片中,并监测I-Response,直到达到结合饱和。(3)解离:使用1x PBS解离分析物。(4)再生:使用1x PBS除去分析物的残留物。(5)洗涤:使用1x PBS进行总共五次洗涤,以彻底去除芯片中的结合和未结合的分析物。

分析:

使用仪器随附的全自动软件进行数据分析。自动分析软件生成具有 KD 值的希尔拟合图。希尔拟合图描述了分析物与目标蛋白的关联作为分析物浓度的函数。达到半极大响应的浓度与 KD 值成正比。低 KD 值表示高绑定亲和力,反之亦然。

为了验证从FEB实验获得的数据,使用数据审查/导出软件从每个分析物浓度的每个读数点提取I-Responses,并可以导出到其他统计分析软件(参见 材料表),如下所述。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

本研究评估了使用FEB技术(一种实时动力学表征方法)的可行性,以确定Hsp90和Cdc37之间的生物分子相互作用。最初的探索性实验(第一个实验)表明,选择适当的分析物浓度是实验的关键部分,并且实验的设计应包括高于和低于KD 值的浓度点,这些浓度点是根据文献中可用的数据预测的。

然而,如果没有关于相互作用的初步信息,我们建议设计一个初步实验,在较?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

这项研究得到了两国科学基金会(BSF)对S.K.S.和N.Q.的资助。

Materials

| Automated analysis software | Agile plus software, Cardea (Nanomed) | NA CAS number: NA |

Referred to in the text as the automated analysis software supplied with the instrument. Generates automated analysis. |

| COOH-BPU (Biosensing Processing Unit) | Agile plus software, Cardea (Nanomed) | NA CAS number: NA |

biosensor chip |

| Data review software | Datalign 1.0, Cardea (Nanomed) | NA CAS number: NA |

Referred to as the supplied data review software in the text. Supplied with the instrument and allows to review and export the information data points. |

| Dialysis bag | CelluSep, Membrane filtration products | T2-10-15 CAS number: NA |

T2 tubings (6,000-8,000 MWCO), (10 mm fw, 6.4mm Ø, 0.32ml/cm, 15m) |

| EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylamino propyl) carbodiimide) | Cardea (Nanomed) | EDC160322-02 CAS number: 25952-53-8 |

White powder |

| ITC (Isothermal titration calorimetry) system | Microcal-PEAQ-ITC (Malvern, United Kingdom) | NA CAS number: NA |

|

| MES (2-(N-morpholino) ethane sulfonic acid) buffer | Merck | M3671-50G CAS number: 4432-31-9 |

White powder |

| NHS (N-Hydroxysulfosuccinimide) chips | Cardea (Nanomed) | NA CAS number: NA |

Graphene-based chip |

| PBS (Phosphate-buffered saline) X 10 | Bio-Lab | 001623237500 CAS number: 7758-11-4 |

Liquid transparent solution |

| Pipete | Thermo Scientific | 11855231 CAS number: NA |

Finnpipette F3 5-50 µL, yellow |

| Quench 1 (3.9 mM amino-PEG5-alcohol in 1 X PBS) | Cardea (Nanomed) | 0105-001-002-001 CAS number: NA |

Liquid, transparent solution |

| Quench 2 (1 M ethanolamine (pH=8.5)) | Cardea (Nanomed) | 0105-001-003-001 CAS number: NA |

Liquid, transparent solution |

| Recombinant protein Cdc37 | Abcam | ab256157 CAS number: NA |

|

| Recombinant protein Hsp90 beta | Abcam | ab80033 CAS number: NA |

|

| Spreadsheet | Excel, Microsoft office | NA CAS number: NA |

|

| Statistical software | GraphPad, Prism | NA CAS number: NA |

Referred to as the other statistical software. Sigma plot, phyton or other statistical programes may also be used |

| Sulfo-NHS | Cardea (Nanomed) | NHS160321-07 CAS number: 106627-54-7 |

White powder |

| Tips | Alex red | LC 1093-800-000 CAS number: NA |

Tip 1-200 µl, in bulk, 1,000 pcs |

References

- Tuncbag, N., Gursoy, A., Guney, E., Nussinov, R., Keskin, O. Architectures and functional coverage of protein-protein interfaces. Journal of Molecular Biology. 381 (3), 785-802 (2008).

- Berggård, T., Linse, S., James, P. Methods for the detection and analysis of protein–protein interactions. Proteomics. 7 (16), 2833-2842 (2007).

- Magliery, T. J., et al. Detecting protein-protein interactions with a green fluorescent protein fragment reassembly trap: Scope and mechanism. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (1), 146-157 (2005).

- Xing, S., Wallmeroth, N., Berendzen, K. W., Grefen, C. Techniques for the analysis of protein-protein interactions in vivo. Plant Physiology. 171 (2), 727-758 (2016).

- Nguyen, T. N., Goodrich, J. A. Protein-protein interaction assays: Eliminating false positive interactions. Nature Methods. 3 (2), 135-139 (2006).

- Fernández-Suárez, M., Chen, T. S., Ting, A. Y. Protein-protein interaction detection in vitro and in cells by proximity biotinylation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (29), 9251-9253 (2008).

- Jiang, M., Niu, C., Cao, J., Ni, D. -. A., Chu, Z. In silico-prediction of protein–protein interactions network about MAPKs and PP2Cs reveals a novel docking site variants in Brachypodium distachyon. Scientific Reports. 8 (1), 15083 (2018).

- Yazawa, M., Sadaghiani, A. M., Hsueh, B., Dolmetsch, R. E. Induction of protein-protein interactions in live cells using light. Nature Biotechnology. 27 (10), 941-945 (2009).

- Wang, W., Goodman, M. T. Antioxidant property of dietary phenolic agents in a human LDL-oxidation ex vivo model: Interaction of protein binding activity. Nutrition Research. 19 (2), 191-202 (1999).

- Xing, S., Wallmeroth, N., Berendzen, K. W., Grefen, C. Techniques for the analysis of protein-protein interactions in vivo. Plant Physiology. 171 (2), 727-758 (2016).

- Qvit, N., Disatnik, M. -. H., Sho, E., Mochly-Rosen, D. Selective phosphorylation inhibitor of delta protein kinase C–Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase protein–protein interactions: Application for myocardial injury in vivo. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 138 (24), 7626-7635 (2016).

- Alam, M. N., Bristi, N. J., Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 21 (2), 143-152 (2013).

- Paulmurugan, R., Gambhir, S. S. Novel fusion protein approach for efficient high-throughput screening of small molecule–mediating protein-protein interactions in cells and living animals. Cancer Research. 65 (16), 7413-7420 (2005).

- Boute, N., Jockers, R., Issad, T. The use of resonance energy transfer in high-throughput screening: BRET versus FRET. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 23 (8), 351-354 (2002).

- Deriziotis, P., Graham, S. A., Estruch, S. B., Fisher, S. E. Investigating protein-protein interactions in live cells using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE. (87), e51438 (2014).

- Ekins, S., Mestres, J., Testa, B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: Methods for virtual ligand screening and profiling. British Journal of Pharmacology. 152 (1), 9-20 (2007).

- Valerio, L. G. Application of advanced in silico methods for predictive modeling and information integration. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 8 (4), 395-398 (2012).

- Piehler, J. New methodologies for measuring protein interactions in vivo and in vitro. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 15 (1), 4-14 (2005).

- Ideker, T., Sharan, R. Protein networks in disease. Genome Research. 18 (4), 644-652 (2008).

- Lu, H., et al. Recent advances in the development of protein–protein interactions modulators: mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 5 (1), 213 (2020).

- Jarosz, D. Hsp90: A global regulator of the genotype-to-phenotype map in cancers. Advances in Cancer Research. 129, 225-247 (2016).

- Johnson, V. A., Singh, E. K., Nazarova, L. A., Alexander, L. D., McAlpine, S. R. Macrocyclic inhibitors of Hsp90. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 10 (14), 1380-1402 (2010).

- Mahalingam, D., et al. Targeting HSP90 for cancer therapy. British Journal of Cancer. 100 (10), 1523-1529 (2009).

- Stewart, A., Fisher, R. A. Co-Immunoprecipitation: Isolation of protein signaling complexes from native tissues. Methods in Cell Biology. 112, 33-54 (2012).

- Pierce, M. M., Raman, C. S., Nall, B. T. Isothermal titration calorimetry of protein-protein interactions. Methods. 19 (2), 213-221 (1999).

- Paketurytė, V., et al. Inhibitor binding to carbonic anhydrases by isothermal titration calorimetry. Carbonic Anhydrase as Drug Target. , 79-95 (2019).

- Grote, J., Dankbar, N., Gedig, E., Koenig, S. Surface plasmon resonance/mass spectrometry interface. Analytical Chemistry. 77 (4), 1157-1162 (2005).

- Kumaraswamy, S., Tobias, R. Label-free kinetic analysis of an antibody–antigen interaction using biolayer interferometry. Methods in Molecular Biology. , 165-182 (2015).

- Wallner, J., Lhota, G., Jeschek, D., Mader, A., Vorauer-Uhl, K. Application of bio-layer interferometry for the analysis of protein/liposome interactions. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 72, 150-154 (2013).

- Singh, A. N., Ramadan, K., Singh, S. Experimental methods to study the kinetics of protein–protein interactions. Advances in Protein Molecular and Structural Biology Methods. , 115-124 (2022).

- Frenzel, D., Willbold, D. Kinetic titration series with biolayer interferometry. PLoS One. 9 (9), 106882 (2014).

- Vu, C. -. A., Chen, W. -. Y. Field-effect transistor biosensors for biomedical applications: Recent advances and future prospects. Sensors. 19 (19), 4214 (2019).

- Bergveld, P. A critical evaluation of direct electrical protein detection methods. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 6 (1), 55-72 (1991).

- Lowe, B. M., Sun, K., Zeimpekis, I., Skylaris, C. K., Green, N. G. Field-effect sensors – from pH sensing to biosensing: sensitivity enhancement using streptavidin–biotin as a model system. The Analyst. 142 (22), 4173-4200 (2017).

- Goldsmith, B. R., et al. Digital biosensing by foundry-fabricated graphene sensors. Scientific Reports. 9 (1), 434 (2019).

- Afsahi, S., et al. Novel graphene-based biosensor for early detection of Zika virus infection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 100, 85-88 (2018).

- Afsahi, S. J., et al. Towards novel graphene-enabled diagnostic assays with improved signal-to-noise ratio. MRS Advances. 2 (60), 3733-3739 (2017).

- Roe, S. M., et al. The mechanism of Hsp90 regulation by the protein kinase-specific cochaperone p50cdc37. Cell. 116 (1), 87-98 (2004).

- Gaiser, A. M., Kretzschmar, A., Richter, K. Cdc37-Hsp90 complexes are responsive to nucleotide-induced conformational changes and binding of further cofactors. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (52), 40921-40932 (2010).

- Popescu, A. I., Găzdaru, D. M., Chilom, C. G., Bacalum, M. Biophysical interactions: Their paramount importance for life. Romanian Reports in Physics. 65 (3), 1063-1077 (2013).

- Surya, S., Abhilash, J., Geethanandan, K., Sadasivan, C., Haridas, M. A profile of protein-protein interaction: Crystal structure of a lectin-lectin complex. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 87, 529-536 (2016).

- Velazquez-Campoy, A., Freire, E. ITC in the post-genomic era…? Priceless. Biophysical Chemistry. 115 (23), 115-124 (2005).

- Concepcion, J., et al. Label-free detection of biomolecular interactions using bioLayer interferometry for kinetic characterization. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening. 12 (8), 791-800 (2009).

- Helmerhorst, E., Chandler, D. J., Nussio, M., Mamotte, C. D. Real-time and label-free bio-sensing of molecular interactions by surface plasmon resonance: A laboratory medicine perspective. The Clinical Biochemist. Reviews. 33 (4), 161-173 (2012).

- Jacob, N. T., et al. Synthetic molecules for disruption of the MYC protein-protein interface. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 26 (14), 4234-4239 (2018).