فحص عالي الإنتاجية للعزلات الميكروبية مع التأثير على صحة Caenorhabditis elegans

Summary

قد تؤثر ميكروبات الأمعاء بشكل إيجابي أو سلبي على صحة مضيفها من خلال آليات محددة أو محفوظة. Caenorhabditis elegans هي منصة ملائمة لفحص مثل هذه الميكروبات. يصف البروتوكول الحالي الفحص عالي الإنتاجية ل 48 عزلة بكتيرية للتأثير على مقاومة إجهاد الديدان الخيطية ، ويستخدم كبديل لصحة الديدان.

Abstract

بفضل صغر حجمها وعمرها القصير وسهولة علم الوراثة ، توفر Caenorhabditis elegans منصة ملائمة لدراسة تأثير العزلات الميكروبية على فسيولوجيا المضيف. كما أنه يتألق باللون الأزرق عند الموت ، مما يوفر وسيلة ملائمة لتحديد الموت. تم استغلال هذه الخاصية لتطوير فحوصات بقاء C. elegans عالية الإنتاجية (LFASS). ويتضمن ذلك تسجيل مضان بفاصل زمني لمجموعات الديدان الموضوعة في صفائح متعددة الآبار ، والتي يمكن من خلالها اشتقاق متوسط وقت الوفاة. تعتمد الدراسة الحالية نهج LFASS لفحص عزلات ميكروبية متعددة في وقت واحد للتأثيرات على قابلية C. elegans للحرارة الشديدة والضغوط التأكسدية. يتم الإبلاغ هنا عن خط أنابيب الفحص الميكروبي هذا ، والذي يمكن استخدامه بشكل ملحوظ لفحص البروبيوتيك مسبقا ، باستخدام مقاومة الإجهاد الشديدة كبديل لصحة المضيف. يصف البروتوكول كيفية زراعة كل من مجموعات عزل ميكروبات الأمعاء C. elegans ومجموعات الديدان المتزامنة في صفائف متعددة الآبار قبل دمجها في المقايسات. يغطي المثال المقدم اختبار 47 عزلة بكتيرية وسلالة تحكم واحدة على سلالتين من الديدان ، في مقايستين للإجهاد بالتوازي. ومع ذلك ، فإن خط أنابيب النهج قابل للتطوير بسهولة وقابل للتطبيق على فحص العديد من الطرائق الأخرى. وبالتالي ، فإنه يوفر إعدادا متعدد الاستخدامات لإجراء مسح سريع للمناظر الطبيعية متعددة المعلمات للظروف البيولوجية والكيميائية الحيوية التي تؤثر على صحة C. elegans.

Introduction

يحتوي جسم الإنسان على ما يقدر بنحو 10-100 تريليون خلية ميكروبية حية (البكتيريا والفطريات القديمة) ، والتي توجد بشكل أساسي في الأمعاء والجلد والبيئات المخاطية1. في حالة صحية ، توفر هذه الفوائد لمضيفها ، بما في ذلك إنتاج الفيتامينات ، ونضج الجهاز المناعي ، وتحفيز الاستجابات المناعية الفطرية والتكيفية لمسببات الأمراض ، وتنظيم التمثيل الغذائي للدهون ، وتعديل استجابات الإجهاد ، وأكثر من ذلك ، مع التأثير على النمو والتطور ، وظهور المرض ، والشيخوخة2،3،4،5 . تتطور ميكروبات الأمعاء أيضا بشكل كبير طوال الحياة. يحدث التطور الأكثر جذرية خلال مرحلة الرضاعة والطفولة المبكرة6 ، ولكن تحدث تغييرات كبيرة أيضا مع تقدم العمر ، بما في ذلك انخفاض في وفرة Bifidobacterium وزيادة في Clostridium و Lactobacillus و Enterobacteriaceae و Enterococcus الأنواع 7. يمكن أن يؤدي نمط الحياة إلى تغيير تكوين ميكروبات الأمعاء مما يؤدي إلى dysbiosis (فقدان البكتيريا المفيدة ، فرط نمو البكتيريا الانتهازية) ، مما يؤدي إلى أمراض مختلفة مثل مرض التهاب الأمعاء والسكري والسمنة5 ، ولكن أيضا المساهمة في مرض الزهايمر وأمراض باركنسون8،9،10،11.

ساهم هذا الإدراك بشكل حاسم في تحسين مفهوم محور الأمعاء والدماغ (GBA) ، حيث تعتبر التفاعلات بين فسيولوجيا الأمعاء (بما في ذلك الآن الميكروبات الموجودة داخلها) والجهاز العصبي المنظم الرئيسي لعملية التمثيل الغذائي للحيوان والوظائف الفسيولوجية12. ومع ذلك ، فإن الدور الدقيق للميكروبات في إشارات الأمعاء والدماغ وآليات العمل المرتبطة بها بعيدة كل البعد عن الفهم الكامل13. مع كون ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء محددا رئيسيا للشيخوخة الصحية ، أصبحت كيفية تعديل البكتيريا لعملية الشيخوخة موضوعا للبحث المكثف والجدل6،14،15.

مع إثبات أن الدودة المستديرة Caenorhabditis elegans تستضيف ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء الصادقة التي تهيمن عليها – كما هو الحال في الأنواع الأخرى – من قبل Bacteroidetes و Firmicutes و Actinobacteria16،17،18،19،20 ، صعودها السريع كمنصة تجريبية لدراسة التفاعلات المشتركة بين المضيفوالأمعاء 21،22،23،24 ، 25،26 وسعت بشكل كبير ترسانة التحقيقلدينا 26،27،28،29. على وجه الخصوص ، يمكن تكييف الأساليب التجريبية عالية الإنتاجية المتاحة ل C. elegans لدراسة النظام الغذائي الجيني ، والتفاعلات الجينية الدوائية ، والممرض الجيني ، وما إلى ذلك ، لاستكشاف كيفية تأثير العزلات البكتيرية والكوكتيلات على صحة C. elegans وشيخوختها بسرعة.

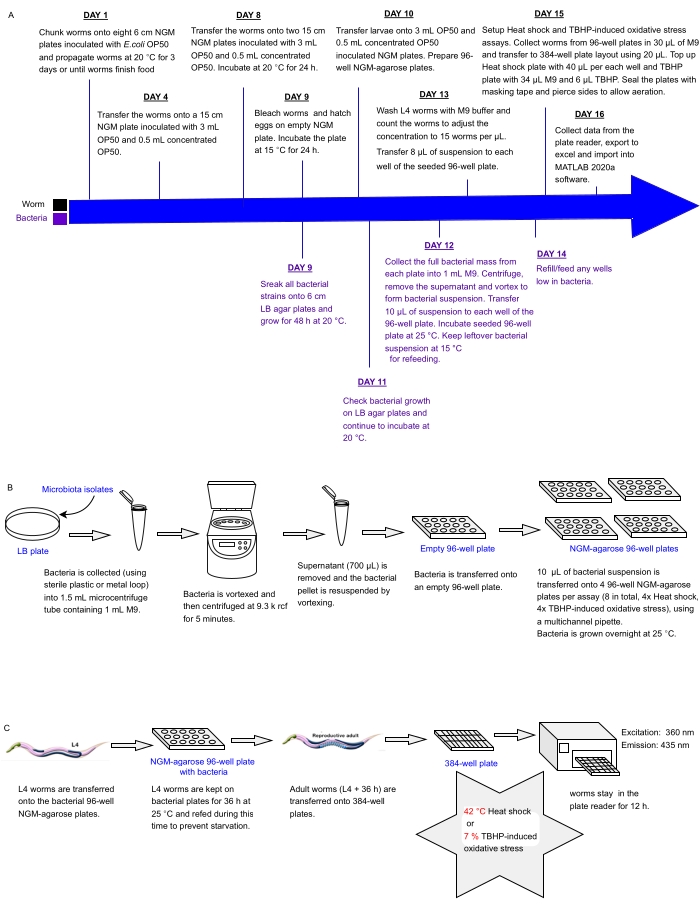

يصف البروتوكول الحالي خط أنابيب تجريبي لفحص صفائف من العزلات البكتيرية أو المخاليط الموضوعة في ألواح متعددة الآبار للتأثيرات على مقاومة الإجهاد C. elegans كبديل للصحة ، والتي يمكن استخدامها لتحديد البروبيوتيك. يوضح بالتفصيل كيفية تنمية أعداد كبيرة من الديدان والتعامل مع المصفوفات البكتيرية في تنسيقات ألواح 96 و 384 بئرا قبل معالجة الديدان لتحليل مقاومة الإجهاد الآلي باستخدام قارئ لوحة مضان (الشكل 1). يعتمد هذا النهج على فحوصات البقاء الآلية الخالية من الملصقات (LFASS)30 التي تستغل ظاهرة مضان الموت31 ، حيث تنتج الديدان المحتضرة دفعة من التألق الأزرق الذي يمكن استخدامه لتحديد وقت الوفاة. ينبعث التألق الأزرق بواسطة استرات الجلوكوزيل لحمض الأنثرانيليك المخزن في حبيبات الأمعاء C. elegans (نوع من العضيات المرتبطة بالليزوزوم) ، والتي تنفجر عندما يتم تشغيل شلال في أمعاء الدودة عند الوفاة31.

الشكل 1: سير العمل التجريبي للفحص عالي الإنتاجية للعزلات البكتيرية مع التأثير على مقاومة C. elegans للإجهاد . (أ) الجدول الزمني لصيانة الديدان والبكتيريا وإعداد المقايسة. (ب) إعداد صفيف صفيحة بكتيرية 96 بئرا والتعامل معها. (ج) إعداد لوحة دودة 384 بئرا. الرجاء الضغط هنا لعرض نسخة أكبر من هذا الشكل.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

تقدم C. elegans العديد من المزايا للفحص السريع للمعلمات التجريبية المتعددة في وقت واحد ، نظرا لصغر حجمها وشفافيتها وتطورها السريع وعمرها القصير وعدم تكلفتها وسهولة التعامل معها. إن الجينوم الأبسط إلى حد كبير ، وخطة الجسم ، والجهاز العصبي ، والأمعاء ، والميكروبيوم ، ولكنه معقد ومشابه بما …

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

نشكر CGC Minnesota (ماديسون ، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية ، NIH – P40 OD010440) لتوفير سلالات دودة و OP50 و Pr. Hinrich Schulenburg (CAU ، كيل ، ألمانيا) لتوفير جميع العزلات الميكروبية البيئية الموضحة هنا. تم تمويل هذا العمل من خلال منحة UKRI-BBSRC إلى AB (BB / S017127 / 1). يتم تمويل JM من خلال منحة دكتوراه FHM بجامعة لانكستر.

Materials

| 10 cm diameter plates (Non-vented) | Fisher Scientific | 10720052 | Venting is not necessary for bacterial cultures |

| 15 cm diameter plates (Vented) | Fisher Scientific | 168381 | |

| 384-well black, transparent flat bottom plates | Corning | 3712 or 3762 | Not essential to be sterile for fast stress assays |

| 6 cm diameter plates (Vented) | Fisher Scientific | 150288 | Venting is necessary for worm cultures to avoid hypoxia |

| 96-well transparent plates (Biolite) | Thermo | 130188 | |

| Agar (<4% ash) | Sigma-Aldrich | 102218041 | Good quality agar is important for the structural integrity of the culture media, to avoid worm burrowing |

| Agarose | Fisher Scientific | BP1356 | |

| Avanti Centrifuge J-26 XP | Beckman coulter | ||

| Bleach | Honeywell | 425044 | |

| Calcium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | C5080 | |

| Centrifuge 5415 R | Eppendorf | ||

| Centrifuge 5810 R | Eppendorf | ||

| Cholesterol | Sigma-Aldrich | C8667 | |

| LB agar | Difco | 240110 | |

| LB broth | Invitrogen | 12795084 | |

| LoBind tips | VWR | 732-1488 | Lo-bind reduce worm loss during transfers |

| LoBind tubes | Eppendorf | 22431081 | |

| Magnesium sulfate | Fisher Scientific | M/1100/53 | |

| Plate reader- infinite M nano+ | Tecan | Monochromator setup enables fluorescence tuning but adequate filter-based setups may be used | |

| Plate reader- Spark | Tecan | ||

| Potassium phosphate monobasic | Honeywell | P0662 | |

| Sodium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | S/3160/63 | |

| Stereomicroscope setup with transillumination base | Leica | MZ6, or M80 | Magnification from 0.6-0.8x up to 40-60x is necessary, as is a good quality transillumination base with a deformable, titable or slidable mirror to adjust contrast |

| t-BHP (tert-Butyl hydroperoxide) | Sigma-Aldrich | 458139 | |

| Transparent adhesive seals Nunc | Fisher Scientific | 101706871 | It is important that it is transparent and that it can tolerate the temperatures involved in the assays. |

| Tryptophan | Sigma-Aldrich | 1278-7099 | |

| Yeast extract | Fisher Scientific | BP1422 |

References

- Krishna, S., et al. Integrating microbiome network: establishing linkages between plants, microbes and human health. The Open Microbiology Journal. 13, 330-342 (2019).

- Amon, P., Sanderson, I. What is the microbiome. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Education & Practice Edition. 102 (5), 257-260 (2017).

- Belkaid, Y., Harrison, O. J. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity. 46 (4), 562-576 (2017).

- Cabreiro, F., Gems, D. Worms need microbes too: microbiota, health and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 5 (9), 1300-1310 (2013).

- Vaga, S., et al. Compositional and functional differences of the mucosal microbiota along the intestine of healthy individuals. Scientific Reports. 10 (1), 14977 (2020).

- Nagpal, R., et al. Gut microbiome and aging: Physiological and mechanistic insights. Nutrition and Healthy Aging. 4 (4), 267-285 (2018).

- Mitsuoka, T. Establishment of intestinal bacteriology. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 33 (3), 99-116 (2014).

- Bonfili, L., et al. Microbiota modulation as preventative and therapeutic approach in Alzheimer’s disease. The FEBS Journal. 288 (9), 2836-2855 (2021).

- Vendrik, K. E. W., et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in neurological disorders. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 10, 98 (2020).

- Wang, Q., et al. The role of gut dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease: mechanistic insights and therapeutic options. Brain. 144 (9), 2571-2593 (2021).

- Zhu, X., et al. The relationship between the gut microbiome and neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroscience Bulletin. 37 (10), 1510-1522 (2021).

- Miller, I. The gut-brain axis: historical reflections. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease. 29 (1), 1542921 (2018).

- Foster, J. A., Rinaman, L., Cryan, J. F. Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress. 7, 124-136 (2017).

- Coman, V., Vodnar, D. C. Gut microbiota and old age: Modulating factors and interventions for healthy longevity. Experimental Gerontology. 141, 111095 (2020).

- Conway, J., Duggal, N. A. Ageing of the gut microbiome: Potential influences on immune senescence and inflammageing. Ageing Research Reviews. 68, 101323 (2021).

- Berg, M., et al. Assembly of the Caenorhabditis elegans gut microbiota from diverse soil microbial environments. The ISME Journal. 10 (8), 1998-2009 (2016).

- Dirksen, P., et al. CeMbio – The Caenorhabditis elegans Microbiome Resource. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 10 (9), 3025-3039 (2020).

- Dirksen, P., et al. The native microbiome of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: gateway to a new host-microbiome model. BMC Biology. 14, 38 (2016).

- Samuel, B. S., Rowedder, H., Braendle, C., Felix, M. A., Ruvkun, G. Caenorhabditis elegans responses to bacteria from its natural habitats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (27), 3941-3949 (2016).

- Zimmermann, J., et al. The functional repertoire contained within the native microbiota of the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. The ISME Journal. 14 (1), 26-38 (2020).

- Dinic, M., et al. Host-commensal interaction promotes health and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans through the activation of HLH-30/TFEB-mediated autophagy. Aging. 13 (6), 8040-8054 (2021).

- Goya, M. E., et al. Probiotic Bacillus subtilis protects against alpha-Synuclein aggregation in C. elegans. Cell Reports. 30 (2), 367-380 (2020).

- Hacariz, O., Viau, C., Karimian, F., Xia, J. The symbiotic relationship between Caenorhabditis elegans and members of its microbiome contributes to worm fitness and lifespan extension. BMC Genomics. 22 (1), 364 (2021).

- Shin, M. G., et al. Bacteria-derived metabolite, methylglyoxal, modulates the longevity of C. elegans through TORC2/SGK-1/DAF-16 signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (29), 17142-17150 (2020).

- Zhang, F., et al. Natural genetic variation drives microbiome selection in the Caenorhabditis elegans gut. Current Biology. 31 (12), 2603-2618 (2021).

- Zhang, F., et al. High-throughput assessment of changes in the Caenorhabditis elegans gut microbiome. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2144, 131-144 (2020).

- Chan, J. P., et al. Using bacterial transcriptomics to investigate targets of host-bacterial interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans. Scientific Reports. 9 (1), 5545 (2019).

- Hartsough, L. A., et al. Optogenetic control of gut bacterial metabolism to promote longevity. Elife. 9, 56849 (2020).

- Pryor, R., et al. Host-microbe-drug-nutrient screen identifies bacterial effectors of Metformin therapy. Cell. 178 (6), 1299-1312 (2019).

- Benedetto, A., et al. New label-free automated survival assays reveal unexpected stress resistance patterns during C. elegans aging. Aging Cell. 18 (5), 12998 (2019).

- Coburn, C., et al. Anthranilate fluorescence marks a calcium-propagated necrotic wave that promotes organismal death in C. elegans. PLOS Biology. 11 (7), 1001613 (2013).

- Porta-de-la-Riva, M., Fontrodona, L., Villanueva, A., Ceron, J. Basic Caenorhabditis elegans methods: synchronization and observation. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (64), e4019 (2012).

- Stiernagle, T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook. , 1-11 (2006).

- Naomi, R., et al. Probiotics for Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Nutrients. 14 (1), 20 (2021).

- Zheng, S. Y., et al. Potential roles of gut microbiota and microbial metabolites in Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Research Reviews. 69, 101347 (2021).

- Gill, M. S., Olsen, A., Sampayo, J. N., Lithgow, G. J. An automated high-throughput assay for survival of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 35 (6), 558-565 (2003).

- Park, H. -. E. H., Jung, Y., Lee, S. -. J. V. Survival assays using Caenorhabditis elegans. Molecules and Cells. 40 (2), 90-99 (2017).

- Partridge, F. A., et al. An automated high-throughput system for phenotypic screening of chemical libraries on C. elegans and parasitic nematodes. International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance. 8 (1), 8-21 (2018).

- Rahman, M., et al. NemaLife chip: a micropillar-based microfluidic culture device optimized for aging studies in crawling C. elegans. Scientific Reports. 10 (1), 16190 (2020).

- Stroustrup, N., et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan machine. Nature Methods. 10 (7), 665-670 (2013).

- Xian, B., et al. WormFarm: a quantitative control and measurement device toward automated Caenorhabditis elegans aging analysis. Aging Cell. 12 (3), 398-409 (2013).

- Brown, A. E., Schafer, W. R. Unrestrained worms bridled by the light. Nature Methods. 8 (2), 129-130 (2011).

- Churgin, M. A., et al. Longitudinal imaging of Caenorhabditis elegans in a microfabricated device reveals variation in behavioral decline during aging. Elife. 6, 26652 (2017).

- Jushaj, A., et al. Optimized criteria for locomotion-based healthspan evaluation in C. elegans using the WorMotel system. PLoS One. 15 (3), 0229583 (2020).

- Nambyiah, P., Brown, A. E. X. Quantitative behavioural phenotyping to investigate anaesthesia induced neurobehavioural impairment. Scientific Reports. 11 (1), 19398 (2021).

- Squiban, B., Belougne, J., Ewbank, J., Zugasti, O. Quantitative and automated high-throughput genome-wide RNAi screens in C. elegans. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (60), e3448 (2012).

- Zugasti, O., et al. Activation of a G protein-coupled receptor by its endogenous ligand triggers the innate immune response of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature Immunology. 15 (9), 833-838 (2014).

- Zugasti, O., et al. A quantitative genome-wide RNAi screen in C. elegans for antifungal innate immunity genes. BMC Biology. 14, 35 (2016).