- 00:01Concepts

- 03:09Media Preparation

- 05:12Preparing Agar Plates

- 06:21Culturing Host Cells

- 07:30Phage Serial Dilution and Preparation of Bacteria and Phage Overlay

- 10:37Data Analysis and Results

- 11:35Results

プラークアッセイ:プラーク形成単位(PFU)としてウイルス定数を決定する方法

English

Share

Overview

ソース: ティルデ・アンダーソン1, ロルフ・ルード1

1臨床科学ルンド, 感染医学の部門, ルンド大学生物医学センター, 221 00 ルンド, スウェーデン

バクテリオファージまたは単にファージと呼ばれる原核生物に感染するウイルスは、20世紀初頭にTwort(1)とデレル(2)によって独立して同定された。ファージは、その治療価値(3)とヒト(4)、ならびにグローバルな生態系(5)への影響について広く認識されています。現在の懸念は、感染症の治療における現代の抗生物質の代替としてファージの使用に新たな関心を高めています(6)。本質的にすべてのファージ研究は、ウイルスを精製し、ウイルス力を定量する能力に依存しています, また、ウイルス力中剤として知られています.最初に1952年に記載された、これはプラークアッセイ(7)の目的であった。数十年および複数の技術の進歩後、プラークアッセイは、ウイルス力付き(8)の決定のための最も信頼性の高い方法の一つである。

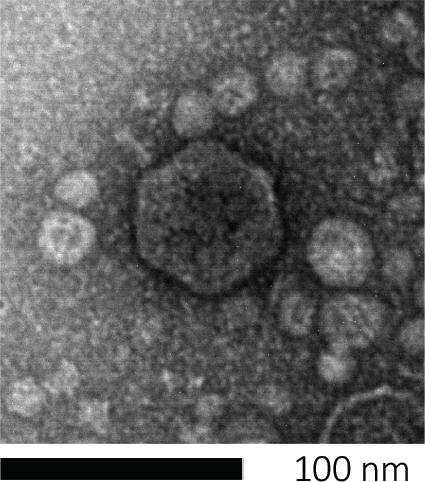

バクテリオファージは、宿主細胞に遺伝物質を注入し、新しいファージ粒子の製造のための機械を乗っ取り、最終的に細胞リシスを通じて多数の子孫を放出させることによって、生き残る。その微小な大きさのために、バクテリオファージは、単に光顕微鏡を使用して観察することはできません。そのため、走査型電子顕微鏡検査が必要です(図1)。さらに、ファージは、餌食に宿主細胞を必要とするので、細菌のような栄養寒天プレート上で栽培することはできません。

図1:バクテリオファージの形態は、ここで大腸菌ファージによって例示され、走査型電子顕微鏡を用いて研究することができる。ほとんどのバクテリオファージは、カウドビレア(尾のバクテリオファージ)に属しています。この特定のファージは、非常に短い尾構造とイコサヘドラルヘッドを有し、ポドウイルスのファミリーに置きます。

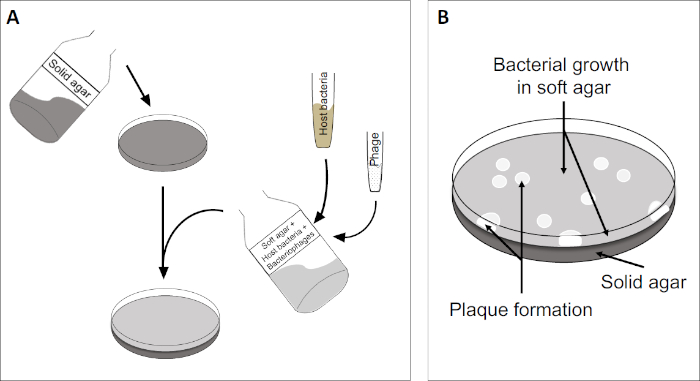

プラークアッセイ(図2)は、宿主細胞の組み込みに基づいており、優先的に対相増殖において、培地に。これは、ウイルスの成長を維持することができる細菌の密な、濁った層を作成します。単離されたファージは、その後感染し、内で複製し、1つの細胞をlyseすることができます。各細胞がlysed細胞で、複数の隣接する細胞が直ちに感染する。いくつかのサイクルで、クリアゾーン(プラーク)は、そうでなければ濁板(図2B/図3A)で観察することができ、最初に単一のバクテリオファージ粒子であったものの存在を示す。試料の体積当たりのプラーク形成単位数(すなわちPFU/mL)は、生成されるプラークの数から決定することができる。

図2:プラーク形成単位(PFU)の試験は、サンプル中のバクテリオファージの数を決定するための一般的な方法である。(A)滅菌ペトリ皿のベースは、適切な固体栄養培地で覆われ、続いて、ソフト培地、感受性宿主細胞および元のバクテリオファージサンプルの希釈が混合される。ファージ懸濁液は、場合によっては、既に固化した柔らかい寒天の表面全体に均等に広がる可能性があることに注意してください。(B)宿主細菌の増殖は、上寒天層に細胞の芝生を形成する。バクテリオファージ複製は、宿主細胞リシスによって引き起こされるクリアゾーン、またはプラークを生成します。

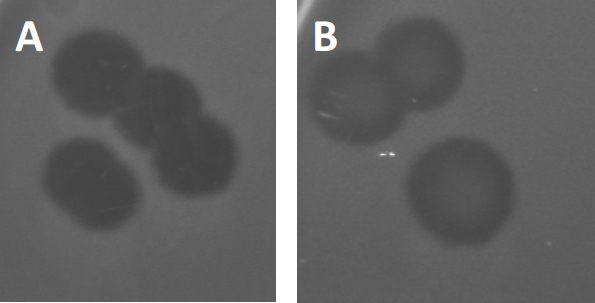

図3:PFU試験の結果は、バクテリオファージによって生成された複数のプラークを示す。感受性宿主細胞のリシスにより、プラークは(A)完全クリアランス、または(B)耐性細菌の生成によって引き起こされる部分的な再増殖(または場合には、または温帯ファージによって、リソジェニックサイクル)。

特定の温帯ファージは、以前に記載された溶解性成長に加えて、リソゲン性のライフサイクルと呼ばれるものを採用することができます。リソジェニーでは、ウイルスは、宿主細胞(9)のゲノムにその遺伝物質を取り込むことを通じて潜伏状態を仮定し、多くの場合、さらなるファージ感染に対する耐性を与える。これは時々プラークのわずかな曇りを通して明らかにされる(図3B)。しかし、以前のファージ感染とは無関係にファージに対する耐性を進化させた細菌の再増殖のためにプラークがぼやけて見えることも注目に値する。

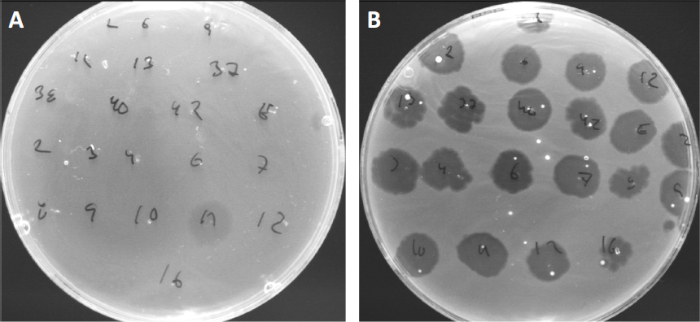

ウイルスは、限られた範囲の宿主細菌にのみ付着または吸着することができる(10)。宿主範囲は、CRISPR-Casシステム(11)のような細胞内抗ウイルス戦略によってさらに制限される。細菌サブグループによって表示される特定のファージに対する耐性/感受性は、歴史的に異なるファージタイプに細菌株を分類するために使用されてきた(図4)。この方法の有効性は、新しいシーケンシング技術によって上回っていますが、ファージタイピングは、例えば、臨床使用のためのファージカクテルの設計を容易にする、細菌とファージの相互作用に関する貴重な情報を提供することができます.

図4:異なる細菌株のファージ感受性。キューチバクテリウム・ニキビ株(A)AD27および(B)AD35を有する柔らかい寒天板を、21種類のC.にきび細菌食症で発見した。唯一のファージ11は、株AD35がすべてのファージに対する感受性を示しながら、AD27に感染し、殺すことができました。ファージタイピングと呼なこの技術は、ファージ感受性に基づいて細菌種と株を異なるサブグループに分割するために使用することができる。

Procedure

Applications and Summary

Despite multiple technological advances, plaque assays remain the gold standard for determination of viral titer (as PFU) and essential for isolation of pure bacteriophage populations. Susceptible host cells are cultivated in the top coat of a two layered agar-plate, forming a homogenous bed enabling viral replication. The initial event where an isolated bacteriophage in lytic lifecycle infects a cell, replicates within it, and eventually lyses it, is too small to observe. However, the virions released will infect adjacent cells, subsequently giving rise to a clearing zone, or plaque, denoting the presence of a single PFU.

References

- Twort, F. An investigation on the nature of ultra-microscopic viruses. Lancet. 186 (4814): 1241-1243. (1915)

- d'Hérelle, F. An invisible antagonist microbe of dysentery bacillus. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires Des Seances De L Academie Des Sciences. 165: 373-375. (1917)

- Cisek AA, Dąbrowska I, Gregorczyk KP, Wyżewski Z. Phage Therapy in Bacterial Infections Treatment: One Hundred Years After the Discovery of Bacteriophages. Current Microbiology. 74 (2):277-283. (2017)

- Mirzaei MK, Maurice CF. Ménage à trois in the human gut: interactions between host, bacteria and phages. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15 (7):397. (2017)

- Breitbart M, Bonnain C, Malki K, Sawaya NA. Phage puppet masters of the marine microbial realm. Nature Microbiology. 3 (7):754-766. (2018)

- Leung CY, Weitz JS. Modeling the synergistic elimination of bacteria by phage and the innate immune system. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 429:241-252. (2017)

- Dulbecco R. Production of Plaques in Monolayer Tissue Cultures by Single Particles of an Animal Virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 38 (8):747-752. (1952)

- Juarez D, Long KC, Aguilar P, Kochel TJ, Halsey ES. Assessment of plaque assay methods for alphaviruses. J Virol Methods. 187 (1):185-9. (2013)

- Clokie MRJ, Millard AD, Letarov AV, Heaphy S. 2011. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage. 1 (1):31-45. (2011)

- Moldovan R, Chapman-McQuiston E, Wu XL. On kinetics of phage adsorption. Biophys J. 93 (1):303-15. (2007)

- Garneau JE, Dupuis M-È, Villion M, Romero DA, Barrangou R, Boyaval P, Fremaux C, Horvath P, Magadán AH, Moineau S.. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature. 468 (7320):67. (2010)

Transcript

Bacteriophages, also called phages, are viruses that specifically infect bacteria and we can confirm their presence and quantify them using a tool called the plaque assay. Bacteriophages infect their susceptible hosts by first attaching to the bacterial cell wall and injecting their genetic material. Then, they hijack the cell’s biosynthetic machinery to replicate their DNA and produce numerous progeny phage particles, which they then release by lysing and killing the host cell.

This lytic activity is the basis of a widely used phage enumerating technique known as the plaque assay or double agar layer assay. Here, a bacteriophage mix is first prepared in a molten nutrient broth containing low concentration agar. All bacteria used in the mix should be alive and actively dividing in the log phase of their growth, which will ensure that a large percentage of the bacteria are viable and able to form a dense lawn around the plaques. Next, this molten bacterial-phage agar mix is spread over a more solid, concentrated agar nutrient medium which is already solidified on a Petri dish. On incubation at room temperature, the low concentration agar-phage-bacteria broth also solidifies to form a soft agar overlay.

Here, the bacterial cells can derive additional nutrients from the bottom layer and should rapidly multiply to produce a confluent lawn of bacteria. However, as phage particles are also present in the soft layer, these will infect and replicate their genetic material within the bacteria, culminating in cell lysis, which releases multiple progeny. These phage progeny then infect the neighboring cells, as the semi-solid state of the bacteria-phage layer restricts their movement to more distantly located host cells. This cycle of infection and lysis continues over multiple rounds, killing a large number of bacteria in a localized area. The effect of the neighboring cells being destroyed, is to produce a single circular clear zone, called a plaque, which can be seen by the naked eye, effectively amplifying the bacteria lytic activity of the phage and enabling their enumeration.

The number of plaques on a Petri dish are referred to as Plaque-Forming Units, or PFUs, and, providing the initial bacteriophage concentration was sufficiently dilute, should directly correspond to the number of infective phage particles in the original sample. This technique can also be used for characterization of plaque morphology, to aid in identification of phage types, or to isolate phage mutants. In this lab, you will learn how to perform the plaque assay for enumerating phages, using the T7 phage of E. coli as an example.

First, identify a suitable medium for the culturing of the host bacterial cells and the bacteriophage. Here lysogeny broth, or LB medium, was used to culture E. coli and the T7 phage. Next, take three clean glass bottles and label them with media, name, and then the first as LB-Broth, the second as LB-Bottom Agar, and the third as LB-Top Agar. Now, weigh out four grams of pre-formulated LB powder in three sets and then transfer one set of weighed dried media into each bottle. Add 200 milliliters of water to the first bottle. Mix the contents using a magnetic stir bar.

Then, using a pH meter and constant stirring, bring the final pH to 7.4 through the addition of sodium hydroxide or hydrochloric acid. Repeat the water addition and pH adjustment for the other two remaining bottles, as well. Now, weigh out three grams of agar powder and add it to the second bottle to make a 1.5 % bottom agar. Finally, weigh 1. 2 grams of agar and add it to the third bottle to make the .6 % LB top agar. The broth condition in bottle one does not need an agar addition. Cap the bottle semi-tightly and then, sterilize the media by autoclaving at 121 degrees Celsius for 20 minutes. Once complete, remove the media bottles from the autoclave and immediately twist the bottle caps to close them fully to prevent contamination. Keep the LB-Broth and LB-Top Agar media on the bench for later use. Place the LB-Bottom Agar to cool in a water bath that is preset to approximately 45 degrees Celsius.

When the LB-Bottom agar reaches approximately 45 degrees Celsius, transfer it to the work bench. Next, sterilize the workspace using 70 % ethenol. Next, add 450 microliters of sterile one molar calcium chloride to the molten bottom agar to make a final concentration of 2.25 millimolar. Gently swirl the bottle to mix. Then, set out seven clean Petri dishes. Label each dish on the bottom with the media name and preparation date. Then, pour 15 milliliters of the bottom agar into each of the seven Petri dishes. Allow the plates to set for a few hours or overnight at room temperature. Once set, the culture plates can be stored at four degrees Celsius for several days if needed, upside down to minimize condensation. Transfer the Petri dishes from the four degrees Celsius refrigerator to a 37 degrees Celsius incubator one hour before the assay.

The day before the assay is to be preformed, the E. coli should be cultured. Here, 10 microliters of E. coli culture was inoculated into 10 milliliters of LB-Broth. Place the bacteria to grow overnight in a shaking incubator set to 37 degrees Celsius at 160 RPM. Then, on the day of the assay, remove the bacterial culture from the incubator. Seed a fresh 10 milliliters of fresh LB broth with 0.5 milliliters of the overnight culture. Place these cells to grow into a shaking incubator set to 37 degrees Celsius at 160 RPM. Next, use a spectrophotometer to check when this culture reaches log phase growth, indicated by an optical density of 0.5 to 0.7. Once the OD reaches this level, stop the incubation by transferring the cell culture to the bench. They are now ready to be used for phage overlay assay.

Phage titers can vary exponentially across different phage types and samples. So in order to count them effectively, they should be diluted to generate a wide range of phage concentrations. On the day of the assay, generate a series of phage dilutions ranging from one tenth to one millionth concentrations, following a 10-fold dilution technique. To obtain statistically significant and accurate data, perform the serial dilution in triplicate.

Next, melt the solidified LB-top agar using a microwave. Then, place it in a water bath that is preset at 45 degrees Celsius for one hour. After one hour, collect the Petri dishes containing the bottom agar layer from the incubator. Label the plates with phage concentration and assay date. Then, set out seven clean test tubes. Label each test tube with the serial phage dilution number and designate one as control.

When the LB-top agar reaches 45 degrees Celsius, transfer it to the working bench. Now, add 450 microliters of one molar calcium chloride to the 200 milliliter agar to make a final concentration of 2.25 millimolar. Gently swirl the bottle to mix. Next, add 35 milliliters of LB-top agar and four milliliters of bacterial suspension to a sterile conical tube. Gently swirl to evenly distribute the cells but avoid shaking to prevent foaming.

Now, aliquot five milliliters of this bacteria- top agar mix to each of the seven test tubes. Then, transfer 100 microliters of the serially diluted bacteriophage samples and control media, which should be simply media with no bacteriophage, to the respectfully labeled test tubes. Swirl the mixture gently to ensure proper mixing. Gently transfer five milliliters of bacteriophage mix onto the respective Petri plate. Evenly spread the mix throughout the whole surface by gently swirling the Petri plate.

Once all of the Petri plates are layered with the mix, allow solidification of the top layer by incubating at room temperature for 15 minutes. After completion of these steps, repeat the process for the second and then the third sets of the Petri dishes using the remaining two sets of phage dilutions. Seal each dish with parafilm and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes. Place the culture plate upside down at a suitable temperature for 24 hours or until plaques develop. Here, plates were placed in a 37 degrees Celsius incubator for one day, a stimulating growth condition for E. coli and the T7 phage.

Plaques will appear after one to five days of incubation, depending on the bacterial species, incubation conditions, and the choice of medium. Here, plaques were visible after one day of incubation at 37 degrees Celsius. Begin by checking the plates marked control and ensure that no plaques were formed in these plates, as this would indicate viral contamination. To determine the phage titer in the original sample, start with the plates containing the most diluted phage sample first and count the plaques without removing the lids, marking them to indicate which ones have already been counted. Repeat the counting for each plate in every set. Some plates might have too many or too few plaques to be counted. Consider 10 to 150 as an ideal plaque count.

Next, generate a table listing the plaque number values for the different dilutions and replicates. Then, calculate the mean plaque number values for the dilution plates that contained the ideal number of plaque counts. In this example, these were the average number of plaques formed in the 10 to the minus three and 10 to the minus four dilution plates. Now, adjust for phage dilution factor by dividing the obtained mean plaque values by the respective phage dilution factors. Here, the average number of plaques formed to the 10 to the minus three and 10 to the minus four dilution plates, were divided by their respective dilution factors to obtain the number of plaque forming units, or PFUs, in 100 microliters of phage mixture. To convert the value to PFU per milliliter, multiply the generated values by 10, as only 100 microliters of phage dilution mix was used during the bacteriophage overlay preparation step, producing an additional dilution factor of 10. Finally, calculate the average of the values obtained from the different dilution plates. This will give the average number of PFUs per milliliter. The number of PFUs corresponds to the number of infective phage particles in the original sample.