- 00:01Concepts

- 03:09Media Preparation

- 05:12Preparing Agar Plates

- 06:21Culturing Host Cells

- 07:30Phage Serial Dilution and Preparation of Bacteria and Phage Overlay

- 10:37Data Analysis and Results

- 11:35Results

플라크 분석: 플라크 형성 단위(PFU)로서 바이러스 역가를 결정하는 방법

English

Share

Overview

출처: 틸드 앤더슨1,롤프 루드1

1 임상 과학 룬드학과, 감염 의학 학과, 생물 의학 센터, 룬드 대학, 221 00 룬드, 스웨덴

박테리오파지 또는 단순히 파지에게 불린 대핵 생물을 감염시키는 바이러스는, Twort (1) 및 d’Hérelle (2)에 의해 20세기 초에 독립적으로 확인되었습니다. 파지는 이후 널리 그들의 치료 값 (3) 및 인간에 미치는 영향에 대 한 그들의 영향에 대 한 인식 되었습니다 (4), 글로벌, 생태계 (5). 현재의 관심사는 전염병의 치료에 현대 항생제에 대한 대안으로 파지의 사용에 대한 새로운 관심을 연료 (6). 본질적으로 모든 파지 연구는 바이러스를 정화하고 정량화하는 능력에 의존합니다, 또한 바이러스 성 미터로 알려진. 처음에 1952년에 기술된, 이것은 플라크 분석의 목적이었습니다 (7). 수십 년 후 여러 기술 발전, 플라크 분석 바이러스 성 titer의 결정에 대 한 가장 신뢰할 수 있는 방법 중 하나 남아 (8).

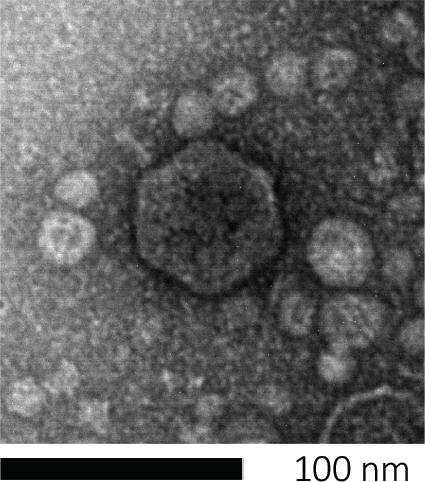

박테리오파지(Bacteriophages)는 유전 물질을 숙주 세포에 주입하고, 새로운 파지 입자의 생산을 위해 기계를 납치하고, 결국 숙주를 세포 용해를 통해 수많은 자손 비리를 방출하도록 유도함으로써 자손을 주입합니다. 그들의 분 크기 때문에, 박테리오파지는 전적으로 가벼운 현미경 검사를 사용하여 관찰될 수 없습니다; 따라서 전자 현미경 검사가 필요합니다 (그림 1). 또한, 파지는 박테리아와 같은 영양 한천 접시에 재배 할 수 없습니다, 그들은 에 먹이 호스트 세포가 필요하기 때문에.

도 1: 대장균 파지에 의해 본래 예시된 박테리오파지의 형태는, 주사 전자 현미경 검사를 사용하여 연구될 수 있다. 대부분의 박테리오파지는 코도바이인(꼬리 박테리오파지)에 속한다. 이 특정 파지는 매우 짧은 꼬리 구조와 icosahedral 머리를 가지고, Podoviruses의 가족에 배치.

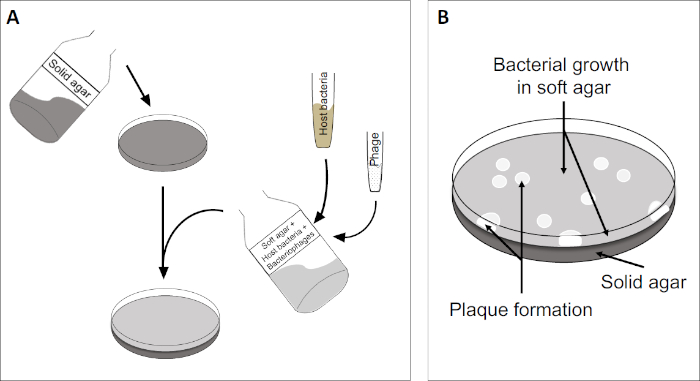

플라크 분석(그림 2)은 로그 상 성장에서 우선적으로 배지로 숙주 셀을 통합하는 것을 기반으로 합니다. 이것은 바이러스 성 성장을 유지할 수 있는 박테리아의 조밀 한, 탁탁 층을 만듭니다. 분리된 파지는 이후에 감염, 복제 및 한 세포를 lyse수 있습니다. 각 lysed 세포로, 다중 인접 한 것 들은 즉시 감염 되 면. 여러 사이클에서, 명확한 영역(플라크)은 그렇지 않으면 탁탁판(도 2B/도 3A)에서관찰될 수 있으며, 이는 처음에 단일 박테리오파지 입자의 존재를 나타낸다. 시료의 부피당 플라크 형성단위(즉, PFU/mL)의 개수는 생성된 플라크 수로부터 결정될 수 있다.

도 2: 플라크 성형 유닛(PFU)에 대한 테스트는 샘플에서 박테리오파지수를 결정하는 일반적인 방법입니다. (A) 멸균 페트리 접시의 베이스는 적절한 고체 영양소 배지로 덮여 있으며, 그 다음으로 소프트 미디어, 취약한 숙주 세포 및 원래 의 박테리오파지 샘플의 희석이 뒤섞인다. 파지 서스펜션은 경우에 따라 이미 고형화된 소프트 한천의 표면을 고르게 퍼뜨릴 수도 있습니다. (B) 숙주 박테리아의 성장은 상단 천층에서 세포의 잔디를 형성한다. 박테리오파지 복제는 숙주 세포 리시스로 인한 명확한 영역 또는 플라크를 생성합니다.

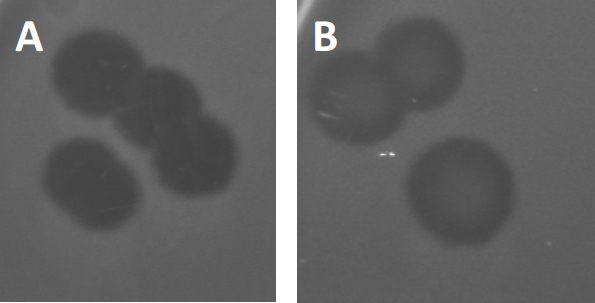

그림 3: PFU 테스트 결과 박테리오파지에서 생성된 여러 플라크가 표시됩니다. 취약한 숙주 세포의 용해로 인해 플라크는 (A) 전체 클리어런스와 함께 세균 잔디의 클리어링 영역으로 볼 수 있으며, (B) 내성 박테리아의 생성에 의한 부분적인 재성장(또는 리소겐성 사이클의 온대 파지에 의해).

특정 온대 파지는 이전에 설명된 lytic 성장 이외에 리소겐성 수명 주기라고 하는 것을 채택할 수 있습니다. 리소겐에서, 바이러스는 호스트 세포의 게놈에 그것의 유전 물질의 통합을 통해 잠복 상태를 가정합니다 (9), 수시로 추가 파지 감염에 저항을 수여합니다. 이것은 때때로 플라크의 약간의 흐린을 통해 드러난다 (그림 3B). 그러나, 그 플라크는 또한 이전 파지 감염의 독립적인 파지에 저항을 발전시킨 박테리아의 재성장 때문에 흐리게 나타날 수 있다는 것을 주목할 가치가 있습니다.

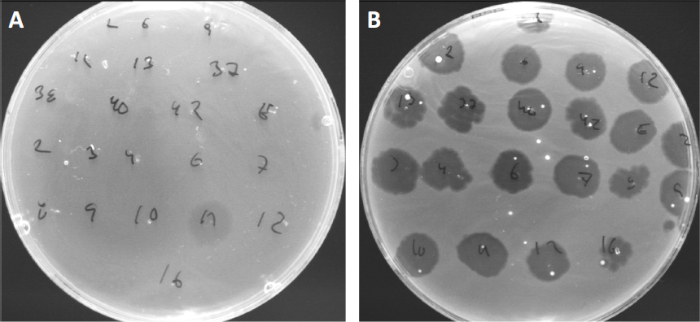

바이러스는 제한된 범위의 숙주 박테리아(10)에만 부착하거나 흡착할 수 있습니다. 호스트 범위는 CRISPR-Cas 시스템(11)과 같은 세포내 항 바이러스 전략에 의해 더욱 제한됩니다. 세균 성 하위 그룹에 의해 표시되는 특정 파지에 대한 저항 /감도는 역사적으로 다른 파지 유형으로 세균균을 분류하는 데 사용되어 왔다 (도 4). 이 방법의 효과는 이제 새로운 시퀀싱 기술에 의해 능가되었지만, 파지 타이핑은 여전히 박테리아 파지 상호 작용에 대한 귀중한 정보를 제공 할 수 있습니다, 예를 들어, 임상 사용을위한 파지 칵테일의 디자인을 촉진.

그림 4: 다른 세균균의 파지 감도. Cutibacterium 여드름 균주 (A) AD27 및 (B) AD35와 부드러운 천 접시, 21 다른 C. 여드름 박테리오파지로 발견되었다. 만 파지 11 감염 하 고 AD27을 죽일 수 있었다 동안 변형 AD35 모든 파지에 대 한 감도 를 보였다. 이 기술, 라는 파지 타이핑, 파지 감수성에 따라 다른 하위 그룹으로 세균종과 균주를 분할 하는 데 사용할 수 있습니다.

Procedure

Applications and Summary

Despite multiple technological advances, plaque assays remain the gold standard for determination of viral titer (as PFU) and essential for isolation of pure bacteriophage populations. Susceptible host cells are cultivated in the top coat of a two layered agar-plate, forming a homogenous bed enabling viral replication. The initial event where an isolated bacteriophage in lytic lifecycle infects a cell, replicates within it, and eventually lyses it, is too small to observe. However, the virions released will infect adjacent cells, subsequently giving rise to a clearing zone, or plaque, denoting the presence of a single PFU.

References

- Twort, F. An investigation on the nature of ultra-microscopic viruses. Lancet. 186 (4814): 1241-1243. (1915)

- d'Hérelle, F. An invisible antagonist microbe of dysentery bacillus. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires Des Seances De L Academie Des Sciences. 165: 373-375. (1917)

- Cisek AA, Dąbrowska I, Gregorczyk KP, Wyżewski Z. Phage Therapy in Bacterial Infections Treatment: One Hundred Years After the Discovery of Bacteriophages. Current Microbiology. 74 (2):277-283. (2017)

- Mirzaei MK, Maurice CF. Ménage à trois in the human gut: interactions between host, bacteria and phages. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15 (7):397. (2017)

- Breitbart M, Bonnain C, Malki K, Sawaya NA. Phage puppet masters of the marine microbial realm. Nature Microbiology. 3 (7):754-766. (2018)

- Leung CY, Weitz JS. Modeling the synergistic elimination of bacteria by phage and the innate immune system. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 429:241-252. (2017)

- Dulbecco R. Production of Plaques in Monolayer Tissue Cultures by Single Particles of an Animal Virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 38 (8):747-752. (1952)

- Juarez D, Long KC, Aguilar P, Kochel TJ, Halsey ES. Assessment of plaque assay methods for alphaviruses. J Virol Methods. 187 (1):185-9. (2013)

- Clokie MRJ, Millard AD, Letarov AV, Heaphy S. 2011. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage. 1 (1):31-45. (2011)

- Moldovan R, Chapman-McQuiston E, Wu XL. On kinetics of phage adsorption. Biophys J. 93 (1):303-15. (2007)

- Garneau JE, Dupuis M-È, Villion M, Romero DA, Barrangou R, Boyaval P, Fremaux C, Horvath P, Magadán AH, Moineau S.. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature. 468 (7320):67. (2010)

Transcript

Bacteriophages, also called phages, are viruses that specifically infect bacteria and we can confirm their presence and quantify them using a tool called the plaque assay. Bacteriophages infect their susceptible hosts by first attaching to the bacterial cell wall and injecting their genetic material. Then, they hijack the cell’s biosynthetic machinery to replicate their DNA and produce numerous progeny phage particles, which they then release by lysing and killing the host cell.

This lytic activity is the basis of a widely used phage enumerating technique known as the plaque assay or double agar layer assay. Here, a bacteriophage mix is first prepared in a molten nutrient broth containing low concentration agar. All bacteria used in the mix should be alive and actively dividing in the log phase of their growth, which will ensure that a large percentage of the bacteria are viable and able to form a dense lawn around the plaques. Next, this molten bacterial-phage agar mix is spread over a more solid, concentrated agar nutrient medium which is already solidified on a Petri dish. On incubation at room temperature, the low concentration agar-phage-bacteria broth also solidifies to form a soft agar overlay.

Here, the bacterial cells can derive additional nutrients from the bottom layer and should rapidly multiply to produce a confluent lawn of bacteria. However, as phage particles are also present in the soft layer, these will infect and replicate their genetic material within the bacteria, culminating in cell lysis, which releases multiple progeny. These phage progeny then infect the neighboring cells, as the semi-solid state of the bacteria-phage layer restricts their movement to more distantly located host cells. This cycle of infection and lysis continues over multiple rounds, killing a large number of bacteria in a localized area. The effect of the neighboring cells being destroyed, is to produce a single circular clear zone, called a plaque, which can be seen by the naked eye, effectively amplifying the bacteria lytic activity of the phage and enabling their enumeration.

The number of plaques on a Petri dish are referred to as Plaque-Forming Units, or PFUs, and, providing the initial bacteriophage concentration was sufficiently dilute, should directly correspond to the number of infective phage particles in the original sample. This technique can also be used for characterization of plaque morphology, to aid in identification of phage types, or to isolate phage mutants. In this lab, you will learn how to perform the plaque assay for enumerating phages, using the T7 phage of E. coli as an example.

First, identify a suitable medium for the culturing of the host bacterial cells and the bacteriophage. Here lysogeny broth, or LB medium, was used to culture E. coli and the T7 phage. Next, take three clean glass bottles and label them with media, name, and then the first as LB-Broth, the second as LB-Bottom Agar, and the third as LB-Top Agar. Now, weigh out four grams of pre-formulated LB powder in three sets and then transfer one set of weighed dried media into each bottle. Add 200 milliliters of water to the first bottle. Mix the contents using a magnetic stir bar.

Then, using a pH meter and constant stirring, bring the final pH to 7.4 through the addition of sodium hydroxide or hydrochloric acid. Repeat the water addition and pH adjustment for the other two remaining bottles, as well. Now, weigh out three grams of agar powder and add it to the second bottle to make a 1.5 % bottom agar. Finally, weigh 1. 2 grams of agar and add it to the third bottle to make the .6 % LB top agar. The broth condition in bottle one does not need an agar addition. Cap the bottle semi-tightly and then, sterilize the media by autoclaving at 121 degrees Celsius for 20 minutes. Once complete, remove the media bottles from the autoclave and immediately twist the bottle caps to close them fully to prevent contamination. Keep the LB-Broth and LB-Top Agar media on the bench for later use. Place the LB-Bottom Agar to cool in a water bath that is preset to approximately 45 degrees Celsius.

When the LB-Bottom agar reaches approximately 45 degrees Celsius, transfer it to the work bench. Next, sterilize the workspace using 70 % ethenol. Next, add 450 microliters of sterile one molar calcium chloride to the molten bottom agar to make a final concentration of 2.25 millimolar. Gently swirl the bottle to mix. Then, set out seven clean Petri dishes. Label each dish on the bottom with the media name and preparation date. Then, pour 15 milliliters of the bottom agar into each of the seven Petri dishes. Allow the plates to set for a few hours or overnight at room temperature. Once set, the culture plates can be stored at four degrees Celsius for several days if needed, upside down to minimize condensation. Transfer the Petri dishes from the four degrees Celsius refrigerator to a 37 degrees Celsius incubator one hour before the assay.

The day before the assay is to be preformed, the E. coli should be cultured. Here, 10 microliters of E. coli culture was inoculated into 10 milliliters of LB-Broth. Place the bacteria to grow overnight in a shaking incubator set to 37 degrees Celsius at 160 RPM. Then, on the day of the assay, remove the bacterial culture from the incubator. Seed a fresh 10 milliliters of fresh LB broth with 0.5 milliliters of the overnight culture. Place these cells to grow into a shaking incubator set to 37 degrees Celsius at 160 RPM. Next, use a spectrophotometer to check when this culture reaches log phase growth, indicated by an optical density of 0.5 to 0.7. Once the OD reaches this level, stop the incubation by transferring the cell culture to the bench. They are now ready to be used for phage overlay assay.

Phage titers can vary exponentially across different phage types and samples. So in order to count them effectively, they should be diluted to generate a wide range of phage concentrations. On the day of the assay, generate a series of phage dilutions ranging from one tenth to one millionth concentrations, following a 10-fold dilution technique. To obtain statistically significant and accurate data, perform the serial dilution in triplicate.

Next, melt the solidified LB-top agar using a microwave. Then, place it in a water bath that is preset at 45 degrees Celsius for one hour. After one hour, collect the Petri dishes containing the bottom agar layer from the incubator. Label the plates with phage concentration and assay date. Then, set out seven clean test tubes. Label each test tube with the serial phage dilution number and designate one as control.

When the LB-top agar reaches 45 degrees Celsius, transfer it to the working bench. Now, add 450 microliters of one molar calcium chloride to the 200 milliliter agar to make a final concentration of 2.25 millimolar. Gently swirl the bottle to mix. Next, add 35 milliliters of LB-top agar and four milliliters of bacterial suspension to a sterile conical tube. Gently swirl to evenly distribute the cells but avoid shaking to prevent foaming.

Now, aliquot five milliliters of this bacteria- top agar mix to each of the seven test tubes. Then, transfer 100 microliters of the serially diluted bacteriophage samples and control media, which should be simply media with no bacteriophage, to the respectfully labeled test tubes. Swirl the mixture gently to ensure proper mixing. Gently transfer five milliliters of bacteriophage mix onto the respective Petri plate. Evenly spread the mix throughout the whole surface by gently swirling the Petri plate.

Once all of the Petri plates are layered with the mix, allow solidification of the top layer by incubating at room temperature for 15 minutes. After completion of these steps, repeat the process for the second and then the third sets of the Petri dishes using the remaining two sets of phage dilutions. Seal each dish with parafilm and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes. Place the culture plate upside down at a suitable temperature for 24 hours or until plaques develop. Here, plates were placed in a 37 degrees Celsius incubator for one day, a stimulating growth condition for E. coli and the T7 phage.

Plaques will appear after one to five days of incubation, depending on the bacterial species, incubation conditions, and the choice of medium. Here, plaques were visible after one day of incubation at 37 degrees Celsius. Begin by checking the plates marked control and ensure that no plaques were formed in these plates, as this would indicate viral contamination. To determine the phage titer in the original sample, start with the plates containing the most diluted phage sample first and count the plaques without removing the lids, marking them to indicate which ones have already been counted. Repeat the counting for each plate in every set. Some plates might have too many or too few plaques to be counted. Consider 10 to 150 as an ideal plaque count.

Next, generate a table listing the plaque number values for the different dilutions and replicates. Then, calculate the mean plaque number values for the dilution plates that contained the ideal number of plaque counts. In this example, these were the average number of plaques formed in the 10 to the minus three and 10 to the minus four dilution plates. Now, adjust for phage dilution factor by dividing the obtained mean plaque values by the respective phage dilution factors. Here, the average number of plaques formed to the 10 to the minus three and 10 to the minus four dilution plates, were divided by their respective dilution factors to obtain the number of plaque forming units, or PFUs, in 100 microliters of phage mixture. To convert the value to PFU per milliliter, multiply the generated values by 10, as only 100 microliters of phage dilution mix was used during the bacteriophage overlay preparation step, producing an additional dilution factor of 10. Finally, calculate the average of the values obtained from the different dilution plates. This will give the average number of PFUs per milliliter. The number of PFUs corresponds to the number of infective phage particles in the original sample.