植物标本标本的鲁棒 DNA 分离与高通量测序库建设

Summary

本文阐述了从植物标本室材料中提取 dna 隔离和高通量测序库的详细协议, 包括抢救异常质量较差的 dna。

Abstract

标本室是一种宝贵的植物材料来源, 可用于各种生物研究。植物标本标本的使用与一些挑战, 包括样本保存质量, 退化的 DNA, 和破坏性抽样稀有标本。为了更有效地利用大型测序工程中的植物标本库材料, 需要一种可靠、可伸缩的 DNA 分离和制备方法。本文展示了一种健壮的, 从不需要对单个样本进行修改的标本标本中进行的 DNA 隔离和高通量库构建的鲁棒的起始到端协议。本协议是为低品质干燥的植物材料量身定做的, 利用现有的方法, 优化组织磨削, 修改库尺寸选择, 并为低产量库引入可选的 reamplification 步骤。低产量 DNA 库的 Reamplification 可以拯救来自不可替代和潜在价值的植物标本标本的样本, 否定额外的破坏性取样的需要, 不引入可识别的顺序偏差, 共同系统进化应用。该议定书已在数以百计的草种上进行了测试, 但预计在验证后能适应其他植物血统的使用。这个协议可以受到极退化的 DNA 的限制, 在那里碎片不存在于所需的大小范围内, 而在某些植物材料中存在的次生代谢物会抑制干净的 dna 分离。总的来说, 该协议引入了一种快速而全面的方法, 允许 DNA 隔离和图书馆准备24样本在少于13小时, 只有8小时的主动动手时间与最小的修改。

Introduction

植物标本集是一个潜在的有价值的物种和基因组多样性的来源的研究, 包括系统学 1, 2, 3, 人口遗传学 4, 5, 保护生物6, 入侵物种生物7和特征演变8。获得丰富多样的物种、种群、地理位置和时间点的能力突出了 “宝箱”9 , 即标本馆。从历史上看, 植物标本所衍生的 DNA 退化的性质阻碍了 PCR 的项目, 往往贬低研究人员只使用高拷贝中发现的标记, 如叶绿体基因组的区域或核糖体的内部转录间隔 (其)rna.标本和 DNA 的质量因保存9、10的方法而有很大的差异, 在干燥过程中使用的热的双绞碎和破碎是最常见的损害形式, 造成所谓的 90% DNA 锁定, 已使基于 PCR 的研究11。除了碎片, 植物标本组学的第二个最普遍的问题是污染, 例如从内生真菌中提取的13或真菌在收集后死后被采集, 但在标本室中安装12之前, 虽然这个问题可以解决 bioinformatically 给出正确的真菌数据库 (见下文)。第三个和更不常见的问题是通过胞嘧啶脱氨作用 (C/G→T/A)14 进行序列修改, 虽然估计在标本标本11 中的低 (~ 0.03%)。随着高通量测序 (高温超导) 的出现, 碎片问题可以通过短读取和排序深度12,15来克服, 从而允许从许多质量较低的样本中获取基因组级数据。DNA, 甚至有时允许整个基因组排序15。

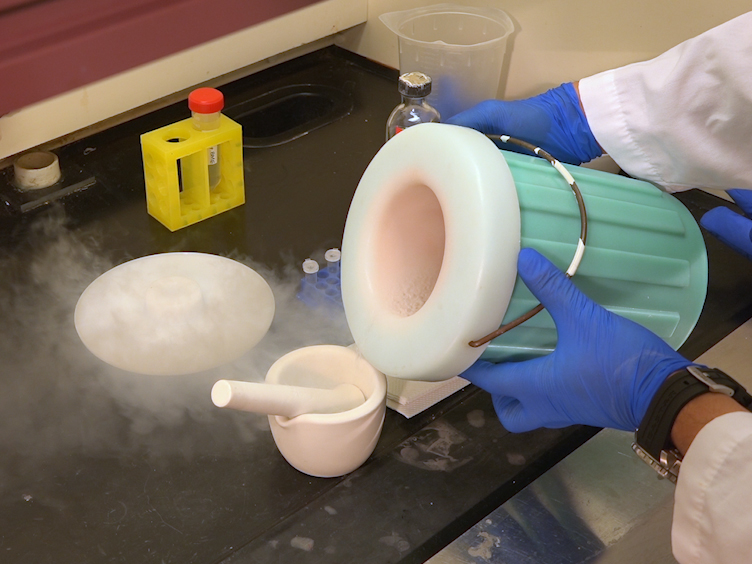

标本室标本越来越多地被使用, 是系统发育项目的一个更大的组成部分16。目前的挑战是使用植物标本标本为高温超导始终获得足够的双链 DNA, 一个必要的先决条件, 排序协议, 从众多物种及时, 不需要优化的方法, 个别标本.本文介绍了一种利用现有方法进行 DNA 提取和库标本制备的协议, 并对其进行修改, 以实现快速、可复制的结果。该方法允许从标本到24个样本库的完整处理, 在13小时, 具有8小时的动手时间, 或 16 h, 与 9 h 的实际操作时间, 当需要可选的 reamplification 步骤。同时处理更多的样品是可以实现的, 虽然限制因素是离心能力和技术技能。该协议的目的是只需要典型的实验室设备 (thermocycler, 离心机和磁性支架), 而不是专门的设备, 如喷雾器或 sonicator, 为剪切 DNA。

在高通量测序实验中, DNA 质量、片段大小和数量是限制标本标本使用的因素。其他隔离标本室 dna 和创建高通量测序库的方法表明, 使用10的 DNA16的效用不大;然而, 它们需要实验性地确定图书馆准备所需的最佳 PCR 周期数。当处理极少量可行的双链 DNA (dsDNA) 时, 这种方法变得不切实际, 因为有些标本标本只为单个库的制备提供了足够的 dna。这里提出的方法使用单一数量的周期, 不管样本质量如何, 所以在库优化步骤中没有丢失 DNA。相反, 当库不满足排序所需的最小金额时, 将调用 reamplification 步骤。许多植物标本是罕见的, 并拥有很少的材料, 使得难以证明破坏性抽样在许多情况下。为了对付这一问题, 所提出的协议允许 dsDNA 的输入大小小于1.25 到库的准备过程, 扩大了可行样本的范围, 以高通量测序, 并尽量减少对样本的破坏性抽样的需要。

下面的协议已经为牧草进行了优化, 并在标本室标本上对数以百计的不同物种进行了测试, 尽管我们预计该协议可以应用于许多其他植物群。它包括一个可选的恢复步骤, 可用于保存低质量和/或稀有标本。根据200余种标本标本, 本协议适用于组织投入和质量低的标本, 可通过最小的破坏性抽样保存稀有标本。这里表明, 该协议可以提供高质量的库, 可以为基于 phylogenomics 的项目排序。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

本协议是一种综合可靠的方法, 用于 DNA 分离和测序库的干燥标本的制备。该方法的一致性和最小的需要改变它的基础上标本质量, 使它可伸缩的大型植物标本的排序项目。为低收益库包含一个可选的 reamplification 步骤, 允许包含低质量、低数量、稀有或历史上重要的样本, 否则将不适合排序。

初始 DNA 产量的重要性

标本室衍生的 dna 通常被降级为最初的标本保存<…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

我们感谢泰勒 AuBuchon-长老, 约旦 Teisher 和克里斯汀娜 Zudock 协助取样标本, 和密苏里植物园, 以获得植物标本标本的破坏性取样。这项工作得到了国家科学基金会 (DEB-1457748) 的资助。

Materials

| Veriti Thermal Cycler | Applied Biosystems | 4452300 | 96 well |

| Gel Imaging System | Azure Biosystems | c300 | |

| Microfuge 20 Series | Beckman Coulter | B30137 | |

| Digital Dry Bath | Benchmark Scientific | BSH1001 | |

| Electrophoresis System | EasyCast | B2 | |

| PURELAB flex 2 (Ultra pure water) | ELGA | 89204-092 | |

| DNA LoBind Tube | Eppendorf | 30108078 | 2 ml |

| Mini centrifuge | Fisher Scientific | 12-006-901 | |

| Vortex-Genie 2 | Fisher Scientific | 12-812 | |

| Mortar | Fisher Scientific | S02591 | porcelain |

| Pestle | fisher Scientific | S02595 | porcelain |

| Centrifuge tubes | fisher Scientific | 21-403-161 | |

| Microwave | Kenmore | 405.7309231 | |

| Qubit Assay Tubes | Invitrogen | Q32856 | |

| 0.2 ml Strip tube and Cap for PCR | VWR | 20170-004 | |

| Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer | Invitrogen | Q32866 | |

| Balance | Mettler Toledo | PM2000 | |

| Liquid Nitrogen Short-term Storage | Nalgene | F9401 | |

| Magnetic-Ring Stand | ThermoFisher Scientific | AM10050 | 96 well |

| Water Bath | VWR | 89032-210 | |

| Hot Plate Stirrers | VWR | 97042-754 | |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Airgas | UN1977 | |

| 1 X TE Buffer | Ambion | AM9849 | pH 8.0 |

| CTAB | AMRESCO | 0833-500G | |

| 2-MERCAPTOETHANOL | AMRESCO | 0482-200ML | |

| Ribonuclease A | AMRESCO | E866-5ML | 10 mg/ml solution |

| Agencourt AMPure XP | Beckman Coulter | A63882 | |

| Sodium Chloride | bio WORLD | 705744 | |

| Isopropyl Alcohol | bio WORLD | 40970004-1 | |

| Nuclease Free water | bio WORLD | 42300012-2 | |

| Isoamyl Alcohol | Fisher Scientific | A393-500 | |

| Sodium Acetate Trihydrate | Fisher Scientific | s608-500 | |

| LE Agarose | GeneMate | E-3120-500 | |

| 100bp PLUS DNA Ladder | Gold Biotechnology | D003-500 | |

| EDTA, Disodium Salt | IBI Scientific | IB70182 | |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Life Technologies | Q32854 | |

| TRIS | MP Biomedicals | 103133 | ultra pure |

| Gel Loading Dye Purple (6 X) | New England BioLabs | B7024S | |

| NEBNext dsDNA Fragmentase | New England BioLabs | M0348L | |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina | New England BioLabs | E7645L | |

| NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina | New England BioLabs | E7600S | Dual Index Primers Set 1 |

| NEBNext Q5 Hot Start HiFi PCR Master Mix | New England BioLabs | M0543L | |

| Mag-Bind RXNPure Plus | Omega bio-tek | M1386-02 | |

| GelRed 10000 X | Pheonix Research | 41003-1 | |

| Phenol solution | SIGMA Life Science | P4557-400ml | |

| PVP40 | SIGMA-Aldrich | PVP40-50G | |

| Chloroform | VWR | EM8.22265.2500 | |

| Ethanol | Koptec | V1016 | 200 Proof |

| Silica sand | VWR | 14808-60-7 | |

| Reamplification primers | Integrated DNA Technologies | see text | |

| Sequencher v.5.0.1 | GeneCodes | ||

References

- Savolainen, V., Cuénoud, P., Spichiger, R., Martinez, M. D. P., Crèvecoeur, M., Manen, J. F. The use of herbarium specimens in DNA phylogenetics: Evaluation and improvement. Plant Syst Evo. 197 (1-4), 87-98 (1995).

- Zedane, L., Hong-Wa, C., Murienne, J., Jeziorski, C., Baldwin, B. G., Besnard, G. Museomics illuminate the history of an extinct, paleoendemic plant lineage (Hesperelaea, Oleaceae) known from an 1875 collection from Guadalupe Island, Mexico. Bio J Linn Soc. 117 (1), 44-57 (2016).

- Teisher, J. K., McKain, M. R., Schaal, B. A., Kellogg, E. A. Polyphyly of Arundinoideae (Poaceae) and Evolution of the Twisted Geniculate Lemma Awn. Ann Bot. , (2017).

- Cozzolino, S., Cafasso, D., Pellegrino, G., Musacchio, A., Widmer, A. Genetic variation in time and space: the use of herbarium specimens to reconstruct patterns of genetic variation in the endangered orchid Anacamptis palustris. Conserv Gen. 8 (3), 629-639 (2007).

- Wandeler, P., Hoeck, P. E. A., Keller, L. F. Back to the future: museum specimens in population genetics. Tre Eco & Evo. 22 (12), 634-642 (2007).

- Rivers, M. C., Taylor, L., Brummitt, N. A., Meagher, T. R., Roberts, D. L., Lughadha, E. N. How many herbarium specimens are needed to detect threatened species?. Bio Conserv. 144 (10), 2541-2547 (2011).

- Saltonstall, K. Cryptic invasion by a non-native genotype of the common reed, Phragmites australis, into North America. PNAS USA. 99 (4), 2445-2449 (2002).

- Besnard, G., et al. From museums to genomics: old herbarium specimens shed light on a C3 to C4 transition. J Exp Bot. 65 (22), 6711-6721 (2014).

- Särkinen, T., Staats, M., Richardson, J. E., Cowan, R. S., Bakker, F. T. How to open the treasure chest? Optimising DNA extraction from herbarium specimens. PLoS ONE. 7 (8), e43808 (2012).

- Harris, S. A. DNA analysis of tropical plant species: An assessment of different drying methods. Plant Syst Evo. 188 (1-2), 57-64 (1994).

- Staats, M., et al. DNA damage in plant herbarium tissue. PLoS ONE. 6 (12), e28448 (2011).

- Bakker, F. T., et al. Herbarium genomics: plastome sequence assembly from a range of herbarium specimens using an Iterative Organelle Genome Assembly pipeline. Bio J of the Linn Soc. 117 (1), 33-43 (2016).

- Camacho, F. J., Gernandt, D. S., Liston, A., Stone, J. K., Klein, A. S. Endophytic fungal DNA, the source of contamination in spruce needle DNA. Mol Eco. 6 (10), 983-987 (1997).

- Hofreiter, M., Jaenicke, V., Serre, D., Von Haeseler, A., Pääbo, S. DNA sequences from multiple amplifications reveal artifacts induced by cytosine deamination in ancient DNA. Nucl Acids Res. 29 (23), 4793-4799 (2001).

- Staats, M., et al. Genomic treasure troves: Complete genome sequencing of herbarium and insect museum specimens. PLoS ONE. 8 (7), e69189 (2013).

- Bakker, F. T. Herbarium genomics: skimming and plastomics from archival specimens. Webbia. 72 (1), 35-45 (2017).

- Doyle, J. J., Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bul. 19, 11-15 (1987).

- Allen, G. C., Flores-Vergara, M. A., Krasynanski, S., Kumar, S., Thompson, W. F. A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissue using cetryltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat Prot. 1, 2320-2325 (2006).

- Twyford, A. D., Ness, R. D. Strategies for complete plastid genome seqeuncing. Mol Eco Resour. , (2016).

- Aird, D., et al. Analyzing and minimizing PCR amplification bias in Illumina sequencing libraries. Genome Bio. 12 (2), R18 (2011).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M., Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinf. 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Grigoriev, I. V., et al. MycoCosm portal: gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucl Acids Res. 42 (1), D699-D704 (2014).

- Langmead, B., Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Meth. 9 (4), 357-359 (2012).

- Herbarium Genomics. Available from: https://github.com/mrmckain/ (2017)

- . Fast-Plast: Rapid de novo assembly and finishing for whole chloroplast genomes Available from: https://github.com/mrmckain/ (2017)

- McKain, M. R., McNeal, J. R., Kellar, P. R., Eguiarte, L. E., Pires, J. C., Leebens-Mack, J. Timing of rapid diversification and convergent origins of active pollination within Agavoideae (Asparagaceae). Am J Bot. 103 (10), 1717-1729 (2016).

- McKain, M. R., Hartsock, R. H., Wohl, M. M., Kellogg, E. A. Verdant: automated annotation, alignment, and phylogenetic analysis of whole chloroplast genomes. Bioinf. , (2016).

- Staton, S. E., Burke, J. M. Transposome: A toolkit for annotation of transposable element families from unassembled sequence reads. Bioinf. 31 (11), 1827-1829 (2015).

- Bao, W., Kojima, K. K., Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mobile DNA. 6 (1), 11 (2015).

- . Transposons Available from: https://github.com/mrmckain/ (2017)

- Weiß, C. L., et al. Temporal patterns of damage and decay kinetics of DNA retrieved from plant herbarium specimens. Royal Soc Open Sci. 3 (6), 160239 (2016).

- Sawyer, S., Krause, J., Guschanski, K., Savolainen, V., Pääbo, S. Temporal patterns of nucleotide misincorporations and DNA fragmentation in ancient DNA. PLoS ONE. 7 (3), e34131 (2012).

- Head, S. R., et al. Library construction for next-generation sequencing: overviews and challenges. BioTechniques. 56 (2), 61-64 (2014).

- Grover, C. E., Salmon, A., Wendel, J. F. Targeted sequence capture as a powerful tool for evolutionary analysis. Am J Bot. 99, 312-319 (2012).