Gene Digital Circuits Based on CRISPR-Cas Systems and Anti-CRISPR Proteins

Summary

CRISPR-Cas systems and anti-CRISPR proteins were integrated into the scheme of Boolean gates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The new small logic circuits showed good performance and deepened the understanding of both dCas9/dCas12a-based transcription factors and the properties of anti-CRISPR proteins.

Abstract

Synthetic gene Boolean gates and digital circuits have a broad range of applications, from medical diagnostics to environmental care. The discovery of the CRISPR-Cas systems and their natural inhibitors-the anti-CRISPR proteins (Acrs)-provides a new tool to design and implement in vivo gene digital circuits. Here, we describe a protocol that follows the idea of the “Design-Build-Test-Learn” biological engineering cycle and makes use of dCas9/dCas12a together with their corresponding Acrs to establish small transcriptional networks, some of which behave like Boolean gates, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These results point out the properties of dCas9/dCas12a as transcription factors. In particular, to achieve maximal activation of gene expression, dSpCas9 needs to interact with an engineered scaffold RNA that collects multiple copies of the VP64 activation domain (AD). In contrast, dCas12a shall be fused, at the C terminus, with the strong VP64-p65-Rta (VPR) AD. Furthermore, the activity of both Cas proteins is not enhanced by increasing the amount of sgRNA/crRNA in the cell. This article also explains how to build Boolean gates based on the CRISPR-dCas-Acr interaction. The AcrIIA4 fused hormone-binding domain of the human estrogen receptor is the core of a NOT gate responsive to β-estradiol, whereas AcrVAs synthesized by the inducible GAL1 promoter permits to mimic both YES and NOT gates with galactose as an input. In the latter circuits, AcrVA5, together with dLbCas12a, showed the best logic behavior.

Introduction

In 2011, researchers proposed a computational method and developed a corresponding piece of software for the automatic design of digital synthetic gene circuits1. A user had to specify the number of inputs (three or four) and fill in the circuit truth table; this provided all the necessary information to derive the circuit structure using techniques from electronics. The truth table was translated into two Boolean formulae via the Karnaugh map method2. Each Boolean formula is made of clauses that describe logic operations (sum or multiplication) among (part of) the circuit inputs and their negations (the literals). Clauses, in their turn, are either summed up (OR) or multiplied (AND) to compute the circuit output. Every circuit can be realized according to any of its two corresponding formulae: one written in POS (product of sums) form and the other in SOP (sum of products) representation. The former consists of a multiplication of clauses (i.e., Boolean gates) that contain a logic sum of the literals. The latter, in contrast, is a sum of clauses where the literals are multiplied.

Electric circuits can be realized, on a breadboard, by physically wiring different gates together. The electric current permits the exchange of signals among gates, which leads to the computation of the output.

In biology, the situation is more complex. A Boolean gate can be realized as a transcription unit (TU; i.e., the sequence "promoter-coding region-terminator" inside eukaryotic cells), where transcription or translation (or both) are regulated. Thus, at least two kinds of molecules establish a biological wiring: the transcription factor proteins and the non-coding, antisense RNAs1.

A gene digital circuit is organized into two or three layers of gates, namely: 1) the input layer, which is made of YES (buffer) and NOT gates and converts the input chemicals into wiring molecules; 2) the internal layer, which consists of as many TUs as there are clauses in the corresponding Boolean formula. If the circuit is designed according to the SOP formula, every clause in the internal layer will produce the circuit output (e.g., fluorescence) in a so-called distributed output architecture. If the product of sum (POS) formula is used, then a 3) final layer is required, which will contain a single multiplicative gate collecting the wiring molecules from the internal layer.

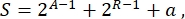

Overall, in synthetic biology, many different schemes can be designed for the same circuit. They differ in the number and the kind of both TUs and wiring molecules. In order to choose the easiest solution to be implemented in yeast cells, each circuit design is associated with a complexity score S, defined as

where A represents the number of activators, R represents the number of repressors, and a is the amount of antisense RNA molecules. If either activators or repressors are absent from the circuit, their contribution to S is zero. Therefore, it is more difficult to realize a circuit scheme in the lab (high S) when it requires a high number of orthogonal transcription factors. This means that new activators and repressors shall be engineered de novo in order to realize the complete wiring inside the digital circuits. In principle, novel DNA-binding proteins can be assembled by using Zinc Finger proteins3 and TAL effectors4 as templates. However, this option appears too arduous and time-consuming; therefore, one should rely mostly on small RNAs and translation regulation to finalize complex gene circuits.

Originally, this method was developed to fabricate digital circuits in bacteria. Indeed, in eukaryotic cells, instead of antisense RNAs, it is more suitable to talk of microRNAs (miRNAs) or small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)5. However, the RNAi pathway is not present in the yeast S. cerevisiae. Hence, one should opt for fully transcriptional networks. Suppose that a circuit needs five activators and five repressors; its complexity score would be S = 32. Circuit complexity can be reduced by replacing the 10 transcription factors with a single dCas96 (nuclease deficient Cas9) fused to an activation domain (AD). As shown in7, dCas9-AD works as a repressor in yeast when binding a promoter between the TATA box and the TSS (transcription start site) and as an activator when binding well upstream of the TATA box. Thus, one can replace 10 transcription factors with a single dCas9-AD fusion protein and 10 sgRNAs (single guide RNAs) for a total complexity score of S = 11. It is quick and easy to synthesize ten sgRNAs, whereas, as previously commented, the assembly of 10 proteins would demand much longer and more complicated work.

Alternatively, one might use two orthogonal dCas proteins (e.g., dCas9 and dCas12a): one to fuse to an AD, and the other bare or in combination with a repression domain. The complexity score would increase by only one unit (S = 12). Hence, CRISPR-dCas systems are the key to the construction of very intricate gene digital circuits in S. cerevisiae.

This paper deeply characterizes the efficiency of both dCas9- and dCas12a-based repressors and activators in yeast. Results show that they do not demand a high amount of sgRNA to optimize their activity, so episomal plasmids are preferentially avoided. Moreover, dCas9-based activators are far more effective when using a scaffold RNA (scRNA) that recruits copies of the VP64 AD. In contrast, dCas12a works well when fused to the strong VPR AD directly. Furthermore, a synthetic activated promoter demands a variable number of target sites, depending on the configuration of the activator (e.g., three when using dCas12a-VPR, six for dCas9-VP64, and only one with dCas9 and a scRNA). As a repressor, dCas12a appears more incisive when binding the coding region rather than the promoter.

As a drawback, however, CRISPR-dCas9/dCas12a do not interact with chemicals directly. Therefore, they might be of no use in the input layer. For this reason, alternative Boolean gate designs containing anti-CRISPR proteins (Acrs) have been investigated. Acrs act on (d)Cas proteins and inhibit their working8. Hence, they are a means to modulate the activity of CRISPR-(d)Cas systems. This paper thoroughly analyzes the interactions between type II Acrs and (d)Cas9, as well as type V Acrs and (d)Cas12a in S. cerevisiae. Since Acrs are much smaller than Cas proteins, a NOT gate responsive to the estrogen β-estradiol was built by fusing the hormone-binding domain of the human estrogen receptor9-HBD(hER)-to AcrIIA4. Besides, a handful of YES and NOT gates that expressed dCas12a(-AD) constitutively and AcrVAs upon induction with galactose were realized. At present, these gates serve only as a proof of concept. However, they also represent the first step toward a deep rethinking of the algorithm to carry out the computational automatic design of synthetic gene digital circuits in yeast cells.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

The protocol showed a possible complete workflow for synthetic gene digital circuits, following the "Design-Build-Test-Learn" (DBTL) biological engineering cycle and concerning both dry-lab and wet-lab experiments. Here, we focused on the CRISPR-Cas system, mainly dSpCas9, denAsCas12a, dLbCas12a, and the corresponding anti-CRISPR proteins, by designing and building in S. cerevisiae small transcriptional networks. Some of them mimicked Boolean gates, which are the basic components of digital circuits. All…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all the students of the Synthetic Biology lab-SPST, TJU-for their general help, together with Zhi Li and Xiangyang Zhang for their assistance in FACS experiments.

Materials

| 0.1 mL PCR 8-strip tubes | NEST | 403112 | |

| 0.2 mL PCR tubes | Axygen | PCR-02-C | |

| 1.5 mL Microtubes | Axygen | MCT-150-C | |

| 15 mL Centrifuge tubes | BIOFIL | CFT011150 | |

| 2 mL Microtubes | Axygen | MCT-200-C | |

| 50 mL Centrifuge tubes | BIOFIL | CFT011500 | |

| Agarose-molecular biology grade | Invitrogen | 75510-019 | |

| Ampicillin sodium salt | Solarbio | 69-52-3 | |

| Applied biosystems veriti 96-well thermal cycler | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 4375786 | |

| AxyPrep DNA gel extraction kit | Axygen | AP-GX-250 | |

| BD FACSuite CS&T research beads | BD | 650621 | Fluorescent beads |

| BD FACSVerse flow cytometer | BD | – | |

| Centrifuge | Eppendorf | 5424 | |

| Centrifuge Sorvall ST 16R | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 75004380 | |

| E. coli competent cells (Strain DH5α) | Life Technologies | 18263-012 | |

| ECL select Western Blotting detection reagent | GE Healthcare | RPN2235 | |

| Electrophoresis apparatus | Beijing JUNYI Electrophoresis Co., Ltd | JY300C | |

| Flat 8-strip caps | NEST | 406012 | |

| Gene synthesis company | Azenta Life Sciences | https://web.azenta.com/zh-cn/azenta-life-sciences | |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 568 | Invitrogen | A-11004 | |

| HiFiScript cDNA synthesis kit | CWBIO | CW2569M | Kit used in step 6.2.2.1 |

| Lysate solution (Zymolyase) | zymoresearch | E1004-A | |

| Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope | Nikon | – | Fluorescence microscope |

| Pipet tips—10 μL | Axygen | T-300-R-S | |

| Pipet tips—1000 μL | Axygen | T-1000-B-R-S | |

| Pipet tips—200 μL | Axygen | T-200-Y-R-S | |

| pRSII403 | Addgene | 35436 | |

| pRSII404 | Addgene | 35438 | |

| pRSII405 | Addgene | 35440 | |

| pRSII406 | Addgene | 35442 | |

| pRSII424 | Addgene | 35466 | |

| pTPGI_dSpCas9_VP64 | Addgene | 49013 | |

| Q5 High-fidelity DNApolymerase | New England Biolabs | M0491 | |

| Restriction enzyme-Acc65I | New England Biolabs | R0599 | |

| Restriction enzyme-BamHI | New England Biolabs | R0136 | |

| Restriction enzyme-SacI-HF | New England Biolabs | R3156 | |

| Restriction enzyme-XhoI | New England Biolabs | R0146 | |

| Roche LightCycler 96 | Roche | – | Real-Time PCR Instrument |

| S. cerevisiae CEN.PK2-1C | – | – | The parent strain. The genotype is: MATa; his3D1; leu2-3_112; ura3-52; trp1-289; MAL2-8c; SUC2 |

| Stem-Loop Kit | SparkJade | AG0502 | Kit used in step 6.2.1.3 |

| T100 Thermal Cycler | BIO-RAD | 186-1096 | |

| T4 DNA ligase | New England Biolabs | M0202 | |

| T5 Exonuclease | New England Biolabs | M0363 | |

| Taq DNA ligase | New England Biolabs | M0208 | |

| Taq DNA polymerase | New England Biolabs | M0495 | |

| TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus)(2x) (SYBR Green I dye) | Takara | RR820Q | |

| YeaStar RNA kit | Zymo Research | R1002 | |

| β-estradiol | Sigma-Aldrich | E8875 |

References

- Marchisio, M. A., Stelling, J. Automatic design of digital synthetic gene circuits. PLOS Computational Biology. 7 (2), 1001083 (2011).

- Karnaugh, M. The map method for synthesis of combinational logic circuits. Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. 72 (9), 593-599 (1953).

- Mandell, J. G., Barbas, C. F. Zinc finger tools: custom DNA-binding domains for transcription factors and nucleases. Nucleic Acids Research. 34, 516-523 (2006).

- Bogdanove, A. J., Voytas, D. F. TAL effectors: customizable proteins for DNA targeting. Science. 333 (6051), 1843-1846 (2011).

- Drinnenberg, I. A., et al. RNAi in budding yeast. Science. 326 (5952), 544-550 (2009).

- Gander, M. W., Vrana, J. D., Voje, W. E., Carothers, J. M., Klavins, E. Digital logic circuits in yeast with CRISPR-dCas9 NOR gates. Nature Communications. 8, 15459 (2017).

- Farzadfard, F., Perli, S. D., Lu, T. K. Tunable and multifunctional eukaryotic transcription factors based on CRISPR/Cas. ACS Synthetic Biology. 2 (10), 604-613 (2013).

- Nakamura, M., et al. Anti-CRISPR-mediated control of gene editing and synthetic circuits in eukaryotic cells. Nature Communications. 10 (1), 194 (2019).

- Louvion, J. F., Havaux-Copf, B., Picard, D. Fusion of GAL4-VP16 to a steroid-binding domain provides a tool for gratuitous induction of galactose-responsive genes in yeast. Gene. 131 (1), 129-134 (1993).

- DiCarlo, J. E., et al. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (7), 4336-4343 (2013).

- Gao, Y., Zhao, Y. Self-processing of ribozyme-flanked RNAs into guide RNAs in vitro and in vivo for CRISPR-mediated genome editing. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 56 (4), 343-349 (2014).

- Jinek, M., et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 337 (6096), 816-821 (2012).

- Zetsche, B., et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 163 (3), 759-771 (2015).

- Fonfara, I., Richter, H., Bratovic, M., Le Rhun, A., Charpentier, E. The CRISPR-associated DNA-cleaving enzyme Cpf1 also processes precursor CRISPR RNA. Nature. 532 (7600), 517-521 (2016).

- Yu, L., Marchisio, M. A. Saccharomyces cerevisiae synthetic transcriptional networks harnessing dCas12a and Type V-A anti-CRISPR proteins. ACS Synthetic Biology. 10 (4), 870-883 (2021).

- Zhang, Y., Marchisio, M. A. Interaction of bare dSpCas9, scaffold gRNA, and type II anti-CRISPR proteins highly favors the control of gene expression in the yeast S. cerevisiae. ACS Synthetic Biology. 11 (1), 176-190 (2022).

- Sheff, M. A., Thorn, K. S. Optimized cassettes for fluorescent protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 21 (8), 661-670 (2004).

- Naito, Y., Hino, K., Bono, H., Ui-Tei, K. CRISPRdirect: software for designing CRISPR/Cas guide RNA with reduced off-target sites. Bioinformatics. 31 (7), 1120-1123 (2015).

- Chee, M. K., Haase, S. B. New and redesigned pRS plasmid shuttle vectors for genetic manipulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2 (5), 515-526 (2012).

- Gibson, D. G. Synthesis of DNA fragments in yeast by one-step assembly of overlapping oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (20), 6984-6990 (2009).

- Froger, A., Hall, J. E. Transformation of plasmid DNA into E. coli using the heat shock method. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (6), e253 (2007).

- Green, M. R., Sambrook, J. . Molecular Cloning. Fourth edition. , (2012).

- Sanger, F. Determination of nucleotide sequences in DNA. Science. 214 (4526), 1205-1210 (1981).

- Gietz, R. D., Woods, R. A. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods in Enzymology. 350, 87-96 (2002).

- Zalatan, J. G., et al. Engineering complex synthetic transcriptional programs with CRISPR RNA scaffolds. Cell. 160 (1-2), 339-350 (2015).

- Song, W., Li, J., Liang, Q., Marchisio, M. A. Can terminators be used as insulators into yeast synthetic gene circuits. Journal of Biological Engineering. 10, 19 (2016).

- Rauch, B. J., et al. Inhibition of CRISPR-Cas9 with bacteriophage proteins. Cell. 168 (1-2), 150-158 (2017).

- Hynes, A. P., et al. An anti-CRISPR from a virulent streptococcal phage inhibits Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9. Nature Microbiology. 2 (10), 1374-1380 (2017).

- Watters, K. E., Fellmann, C., Bai, H. B., Ren, S. M., Doudna, J. A. Systematic discovery of natural CRISPR-Cas12a inhibitors. Science. 362 (6411), 236-239 (2018).

- Chen, C., et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 33 (20), 179 (2005).

- Pfaffl, M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 29 (9), 45 (2001).

- Hahne, F., et al. flowCore: a Bioconductor package for high throughput flow cytometry. BMC Bioinformatics. 10 (1), 106 (2009).

- Li, J., Xu, Z., Chupalov, A., Marchisio, M. A. Anti-CRISPR-based biosensors in the yeast S. cerevisiae. Journal of Biological Engineering. 12, 11 (2018).

- Dong, L., et al. An anti-CRISPR protein disables type V Cas12a by acetylation. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 26 (4), 308-314 (2019).