بسيطة الحرجة الحجم فخذي عيب النموذجي في الفئران

Summary

Animal models are frequently employed to mimic serious bone injury in biomedical research. Due to their small size, establishment of stabilized bone lesions in mice are beyond the capabilities of most research groups. Herein, we describe a simple method for establishing and analyzing experimental femoral defects in mice.

Abstract

While bone has a remarkable capacity for regeneration, serious bone trauma often results in damage that does not properly heal. In fact, one tenth of all limb bone fractures fail to heal completely due to the extent of the trauma, disease, or age of the patient. Our ability to improve bone regenerative strategies is critically dependent on the ability to mimic serious bone trauma in test animals, but the generation and stabilization of large bone lesions is technically challenging. In most cases, serious long bone trauma is mimicked experimentally by establishing a defect that will not naturally heal. This is achieved by complete removal of a bone segment that is larger than 1.5 times the diameter of the bone cross-section. The bone is then stabilized with a metal implant to maintain proper orientation of the fracture edges and allow for mobility.

Due to their small size and the fragility of their long bones, establishment of such lesions in mice are beyond the capabilities of most research groups. As such, long bone defect models are confined to rats and larger animals. Nevertheless, mice afford significant research advantages in that they can be genetically modified and bred as immune-compromised strains that do not reject human cells and tissue.

Herein, we demonstrate a technique that facilitates the generation of a segmental defect in mouse femora using standard laboratory and veterinary equipment. With practice, fabrication of the fixation device and surgical implantation is feasible for the majority of trained veterinarians and animal research personnel. Using example data, we also provide methodologies for the quantitative analysis of bone healing for the model.

Introduction

ويقدر أن نصف سكان الولايات المتحدة يعاني من كسر في سن 65 1. بالنسبة لأولئك المرضى الذين يعانون من كسور المعالجة جراحيا، تشمل 500،000 إجراءات استخدام الكسب غير المشروع العظام 2 و من المتوقع أن يرتفع مع شيخوخة السكان على نحو متزايد 3 هذا العدد . على الرغم من أن العظام هي واحدة من عدد قليل من الأجهزة التي لديها القدرة على شفاء تماما بدون تندب، هناك حالات حيث فشل عملية 3،4. تبعا للظروف ونوعية العلاج، 2-30٪ من كسور العظام الطويلة تفشل، مما أدى إلى عدم النقابات 3،5. في حين لا يزال هناك بعض الجدل حول تعريف، فصال كاذب، وإصابات حرجة الحجم أو غير نقابية العظام تشير بصفة عامة إلى إصابة لا يلتئم على مدى عمر الطبيعي لهذا الموضوع (6). لأغراض تجريبية، هو تقصير هذه المدة إلى متوسط الوقت اللازم للشفاء التام من متوسط الحجم إصابة العظام. تحدث الآفات العظام غير نقابية لالأسطواناتأسباب erous، ولكن العوامل الرئيسية وتشمل الصدمة الشديدة مما أدى إلى وجود فجوة خطيرة الحجم، والعدوى، وضعف الأوعية الدموية، واستخدام التبغ، أو قدرة osteoregenerative تحول دون ذلك بسبب المرض أو العمر 7. حتى لو يتم التعامل غير النقابات بنجاح، فإنه يمكن أن تكلف ما يزيد على 60،000 دولار في الإجراء، وهذا يتوقف على نوع الإصابة والمناهج المستخدمة 8.

وفي الحالات المعتدلة، وتوظيف ذاتي ترقيع العظام. وتتضمن هذه الاستراتيجية استرداد العظام من موقع المانحة وغرس في موقع الإصابة. في حين أن هذا النهج هو فعالة للغاية، وحجم متاح العظام المستمدة المانحة محدود وينطوي على إجراء عملية جراحية إضافية، مما يؤدي إلى ألم مستمر في العديد من المرضى 9،10. وبالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن فعالية من الكسب غير المشروع العظام ذاتي يعتمد على صحة المريض. هي بدائل العظام مصنوعة من مواد تركيبية أو معالجتها العظام جثي متوافرة بكثرة 11-13، لكنها هكتارلقد قيود كبيرة، بما في ذلك سوء خصائص التصاق الخلية المضيفة، وانخفاض osteoconductivity، وإمكانية الرفض المناعي 14. ولذلك هناك حاجة ملحة لتقنيات تجديد العظام التي هي آمنة وفعالة ومتاحة على نطاق واسع.

لدينا القدرة على تحسين استراتيجيات التجدد العظام تعتمد بشكل كبير على القدرة على تقليد الصدمة العظام خطيرة في حيوانات التجارب، ولكن الجيل واستقرار الآفات العظام كبيرة يمثل تحديا تقنيا. في معظم الحالات، يتم تحاكي صدمة خطيرة العظام الطويلة تجريبيا من خلال إنشاء الخلل التي لن تلتئم بشكل طبيعي. على الرغم من أنه يمكن أن تختلف مع الأنواع 15، ويتحقق ذلك عن طريق الإزالة الكاملة للشريحة العظام أكبر من 1.5 مرة من قطر العظام المقطع العرضي 16. ثم يستقر العظام مع زرع المعادن للحفاظ على التوجه السليم من حواف كسر والسماح للتنقل. نظرا لصغر حجمها وهشاشةالعظام الطويلة، وإنشاء مثل هذه الآفات في الفئران هم أبعد من قدرات معظم المجموعات البحثية. على هذا النحو، تقتصر نماذج عيب العظام الطويلة للفئران والحيوانات الكبيرة. ومع ذلك، والفئران تحمل مزايا البحثية الهامة في أنها يمكن المعدلة وراثيا وتربيتها كما سلالات خطر المناعية التي لا نرفض الخلايا البشرية والأنسجة.

لالتطبيقات المستندة إلى خلية الإنسان والفئران خطر المناعية جذابة للعمل مع لأنها من الناحية الفسيولوجية تتميز بشكل جيد، وسهلة المنزل، وفعالة من حيث التكلفة، وسهولة تحليلها شعاعيا وتشريحيا. من الأهمية بمكان أن الفئران خطر المناعية لا يرفض الخلايا من مختلف الأنواع بما في ذلك البشر. يسمح صغر حجمها أيضا اختبار أعداد صغيرة جدا من الخلايا أو مجلدات من السقالات التجريبية في تطبيقات العظام. تم الإبلاغ عن عدة نماذج تقويم العظام الفئران التي تحمل درجات مختلفة من الاستقرار العظام 17،18. تلك التنفسيمللي التي تؤدي إلى مستويات عالية جدا من الاستقرار، مثل المثبتات الخارجية وتأمين لوحات تلتئم في الغالب من قبل التحجر داخل الغشاء على الرغم من أن الشفاء غضروفي وقد تم الإبلاغ عن 19. في المقابل، تلك التي تسمح بعض المتناهية الصغر و / أو الحركة الماكرو، مثل تلك التي تستخدم المسامير النخاعية غير المثبتة أو جزئيا ثابتة، وشفاء بشكل عام مع غلبة التحجر غضروفي 20،21. اتحاد تأخر أو عيوب غير نقابية من العظام الطويلة من الصعب بشكل خاص لتحقيق في الفئران بسبب مستوى إضافي من الاستقرار المطلوب. ومع ذلك، فقد تم الإبلاغ عن عدد من النهج، بما في ذلك دبابيس النخاعية مع المسامير المتشابكة، وتأمين لوحات والمثبتات الخارجية 22. هذه الأنظمة تعمل بشكل جيد عموما، ولكن نظرا تصميم معقد من أنها يمكن أن يكون تحديا تقنيا لتثبيت. على سبيل المثال، جارسيا وآخرون. 23 وضعت على المتشابكة نظام دبوس أنيق للاستخدام في الفئران، ولكن ينطوي على إجراء شقوق في اثنين الموقع مستقلالصورة وتعديل واسع من عظم الفخذ لاستيعاب الدبابيس. وأجريت هذه الإجراءات تحت المجهر تشريح.

هنا، نحن تصف دبوس النخاع الفخذ بسيط مع طوق المركزي تهدف إلى منع إغلاق عجز العظم 3 مم وكذلك ترسيم حواف الأصلية للعيب. في حين دبوس لم يحدد حتى العظم نفسه، وتحجيم دقيق لقطر دبوس والتوسيع من نتائج تجويف النخاع في التدخل كافية للحد من الحركة الالتوائية (الشكل 1). مع اختيار دقيق من العمر الفطرية ونوع الجنس والفئران المتطابقة سلالة، والنتيجة هي تكرار للغاية التصنع غير uniondefect-22 التي يمكن تقييمها بسهولة شعاعيا. وعلاوة على ذلك المناطق ذات الاهتمام يمكن تعريف بتكاثر بعد التصوير المقطعي-حسابها الصغرى (μCT) لقياس دي نوفو تكوين العظام والمعلمات histomorphological. تم نموذج أولي من المسامير في مختبرنا باستخدام أدوات متوفرة بسهولة.

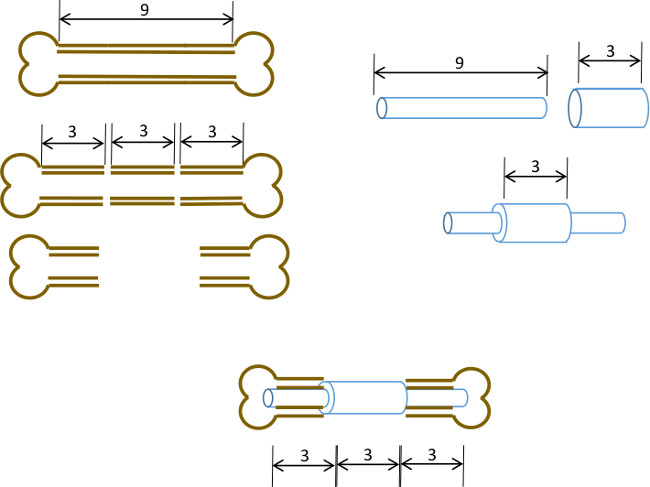

الشكل 1: مبدأ التجريبي ملخص بياني للنموذج الخلل القطعي. يتم استئصاله وسط شريحة 3 ملم من 9-10 ملم عظم الفخذ الفئران جراحيا (يسار). يتم تمرير 3 مم طويل، 19 مقياس أنابيب الصلب الجراحية أكثر من 9 ملم طويلة، 22 G أنبوب الفولاذ المقاوم للصدأ وثابتة بمادة لاصقة في وسط الدقيق (يمين). تم تجهيز دبوس الناتجة في القنوات النخاعية ما تبقى من أجزاء القريبة والبعيدة للعظم الفخذ مع G طوق 19 استبدال جزء 3 ملم من العظم (أدناه، وسط).

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

هنا، نحن تصف طريقة بسيطة لتوليد عيب الحرجة الحجم استقرت دبوس من عظم الفخذ الفئران باستخدام المختبر القياسية والمعدات البيطرية. في حين أن التجمع من المسامير وإجراء العمليات الجراحية في حد ذاته يتطلب الممارسة، فإنه على ما يرام في حدود قدرات عالم أبحاث الطب الحيوي الم?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

ونحن نشكر الموظفين والأطباء البيطريين في وزارة سكوت ومستشفى الأبيض الطب المقارن، معبد بولاية تكساس، للحصول على المشورة التي لا تقدر بثمن والمساعدة خلال تطوير هذه التقنية. وقد تم تمويل هذا العمل في جزء من معهد الطب التجديدي أموال البرنامج، سكوت اند وايت RGP منحة # 90172، NIH 2P40RR017447-07 وNIH R01AR066033-01 (NIAMS). نشكر الدكتورة سوزان زيتوني لعزل المخطوطة.

Materials

| Name of Equipment/Material* | Company | Catalog or model | Notes |

| Pin Assembly | |||

| Dremel rotary tool | Dremel | 8220 | or equivalent |

| Heavy duty cut off wheel | Dremel | 420 | |

| Surgical tubing 19G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMZ8LY | OD 1.07mm, ID 0.889mm |

| Surgical tubing 21G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMZ8YQ | OD 0.82mm, ID 0.635mm |

| Surgical tubing 22G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMYLZS | OD 0.719mm, ID 0.502mm |

| Surgical tubing 23G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FN0SY0 | OD 0.643mm, ID 0.444mm |

| Cyanoacrylate adhesive | Loctite | 1365882 | |

| Emery disc | Dremel | 413 | |

| Rubber polishing point | Dremel | 462 | |

| Felt polishing disc | Dremel | 414 | |

| Gelatin sponge | Surgifoam/Ethicon | 1974 | |

| Punch biopsy cutter | Miltex | 33-34 | |

| Surgery/post-operative | |||

| Warm pad and circulator pump | Stryker/Thermocare | TP700, TP700C, TPP722 | |

| Coverage quaternary spray | Steris | 1429-77 | |

| Bead sterilizer | Germinator/CellPoint Scentific | Germinator 500 | |

| Anesthesia system | VetEquip Inc | 901806 or 901807/901809 | |

| Isofluorane anesthetic | VETone/MWI | 501017, 502017 | |

| Surgical disinfectant | Chloraprep/CareFusion | 260449 | |

| Surgical tools | Fine Science Tools | various | recommend German made |

| Face protection | Splash Shield | 4505 | |

| Rechargable high speed drill | Fine Science Tools | 18000-17 | |

| Diamond cutting wheel | Strauss Diaiond | 361.514.080HP | |

| Absorbable sutures | Covidien | UM-213 | |

| Outer sutures | Ethicon | 668G | or equivalent |

| Vetbond | 3M | 1469SB | or equivalent |

| Hydration gel | Clear H2O | 70-01-1082 | |

| Diet gel | Clear H2O | 72-01-1062 | |

| Buprenorphine | Reckitt and Benckser | 12496-0757-01 | controlled substance |

| Mouse igloos | Bio Serv | K3328, 3570,3327 | |

| Euthanasia cocktail | Euthasol/Virbac | 710101 | controlled substance |

| Analysis | |||

| Live animal imager | Orthoscan | FD Pulse | or equivalent |

| Micro-CT unit and software | Bruker | Skyscan1174 | or equivalent |

| Sealing film/Parafilm M | VWR or Fisher | 100501-338, S37441 | |

| *Generic sources are suitable for all other items such as gause, drapes, protective clothing, animal care equipment. | |||

References

- Brinker, M. R., O’Connor, D. P. The incidence of fractures and dislocations referred for orthopaedic services in a capitated population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 86, 290-297 (2004).

- Cheung, C. The future of bone healing. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 22, 631-641 (2005).

- Rosemont, I. L. . United States Bone and Joint Decade: The burden of musculoskeletal diseases and musculoskeletal injuries. , (2008).

- Tzioupis, C., Giannoudis, P. V. Prevalence of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 38, S3-S9 (2007).

- Marsh, D. Concepts of fracture union, delayed union, and nonunion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. , S22-S30 (1998).

- Spicer, P. P., et al. Evaluation of bone regeneration using the rat critical size calvarial defect. Nat Protoc. 7, 1918-1929 (2012).

- Green, E., Lubahn, J. D., Evans, J. Risk factors, treatment, and outcomes associated with nonunion of the midshaft humerus fracture. J Surg Orthop Adv. 14, 64-72 (2005).

- Kanakaris, N. K., Giannoudis, P. V. The health economics of the treatment of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 38, S77-S84 (2007).

- Dimitriou, R., Mataliotakis, G. I., Angoules, A. G., Kanakaris, N. K., Giannoudis, P. V. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 42, S3-S15 (2011).

- Boer, H. H. The history of bone grafts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. , 292-298 (1988).

- Aro, H. T., Aho, A. J. Clinical use of bone allografts. Ann Med. 25, 403-412 (1993).

- Burstein, F. D. Bone substitutes. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 37, 1-4 (2000).

- Kao, S. T., Scott, D. D. A review of bone substitutes. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 19, 513-521 (2007).

- Boden, S. D. Overview of the biology of lumbar spine fusion and principles for selecting a bone graft substitute. Spine. (Phila Pa 1976). 27, S26-S31 (1976).

- Hollinger, J. O., Kleinschmidt, J. C. The critical size defect as an experimental model to test bone repair materials). J Craniofac Surg. 1, 60-68 (1990).

- Key, J. The effect of local calcium depot on osteogenesis and healing of fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Am). 16, 176-184 (1934).

- Holstein, J. H., et al. Advances in the establishment of defined mouse models for the study of fracture healing and bone regeneration). J Orthop Trauma. 23, S31-S38 (2009).

- Histing, T., et al. Small animal bone healing models: standards, tips, and pitfalls results of a consensus meeting. Bone. 49, 591-599 (2011).

- Cheung, K. M., et al. An externally fixed femoral fracture model for mice. J Orthop Res. 21, 685-690 (2003).

- Hiltunen, A., Vuorio, E., Aro, H. T. A standardized experimental fracture in the mouse tibia. J Orthop Res. 11, 305-312 (1993).

- Manigrasso, M. B., O’Connor, J. P. Characterization of a closed femur fracture model in mice. J Orthop Trauma. 18, 687-695 (2004).

- Garcia, P., et al. Rodent animal models of delayed bone healing and non-union formation: a comprehensive review. Eur Cell Mater. 26, 1-12 (2013).

- Garcia, P., et al. Development of a reliable non-union model in mice. J Surg Res. 147, 84-91 (2008).

- Flecknell, P. A. The relief of pain in laboratory animals. Lab Anim. 18, 147-160 (1984).

- . . Guidelines on the Euthanasia of Animals. , (2013).

- Neill, K. R., et al. Micro-computed tomography assessment of the progression of fracture healing in mice. Bone. 50, 1357-1367 (2012).

- Bagi, C. M., et al. The use of micro-CT to evaluate cortical bone geometry and strength in nude rats: correlation with mechanical testing, pQCT and DXA. Bone. 38, 136-144 (2006).

- Hadjiargyrou, M., et al. Transcriptional profiling of bone regeneration. Insight into the molecular complexity of wound repair. J Biol Chem. 277, 30177-30182 (2002).

- Clough, B. H., et al. Bone regeneration with osteogenically enhanced mesenchymal stem cells and their extracellular matrix proteins. J Bone Miner Res. , (2014).

- Lu, C., et al. Cellular basis for age-related changes in fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 23, 1300-1307 (2005).

- Jepsen, K. J., et al. Genetic variation in the patterns of skeletal progenitor cell differentiation and progression during endochondral bone formation affects the rate of fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 23, 1204-1216 (2008).

- Thayer, T. C., Wilson, S. B., Mathews, C. E. Use of nonobese diabetic mice to understand human type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 39, 541-561 (2010).

- Jee, W. S., Yao, W. Overview: animal models of osteopenia and osteoporosis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 1, 193-207 (2001).