마우스의 간단한 임계 크기의 대퇴 결함 모델

Summary

Animal models are frequently employed to mimic serious bone injury in biomedical research. Due to their small size, establishment of stabilized bone lesions in mice are beyond the capabilities of most research groups. Herein, we describe a simple method for establishing and analyzing experimental femoral defects in mice.

Abstract

While bone has a remarkable capacity for regeneration, serious bone trauma often results in damage that does not properly heal. In fact, one tenth of all limb bone fractures fail to heal completely due to the extent of the trauma, disease, or age of the patient. Our ability to improve bone regenerative strategies is critically dependent on the ability to mimic serious bone trauma in test animals, but the generation and stabilization of large bone lesions is technically challenging. In most cases, serious long bone trauma is mimicked experimentally by establishing a defect that will not naturally heal. This is achieved by complete removal of a bone segment that is larger than 1.5 times the diameter of the bone cross-section. The bone is then stabilized with a metal implant to maintain proper orientation of the fracture edges and allow for mobility.

Due to their small size and the fragility of their long bones, establishment of such lesions in mice are beyond the capabilities of most research groups. As such, long bone defect models are confined to rats and larger animals. Nevertheless, mice afford significant research advantages in that they can be genetically modified and bred as immune-compromised strains that do not reject human cells and tissue.

Herein, we demonstrate a technique that facilitates the generation of a segmental defect in mouse femora using standard laboratory and veterinary equipment. With practice, fabrication of the fixation device and surgical implantation is feasible for the majority of trained veterinarians and animal research personnel. Using example data, we also provide methodologies for the quantitative analysis of bone healing for the model.

Introduction

그것은 치료 골절 환자의 경우 수술, 50 만 절차 골 이식 2의 사용을 포함한다. 미국 인구의 절반이 65 일의 나이 골절이 발생할 것으로 추정되며,이 숫자는 점점 고령화 3 증가 할 것으로 예상된다 . 뼈가 완전히 흉터없이 치유 능력을 갖는 몇몇 기관 중 하나이지만 프로세스 3,4-을하지 아니한 경우, 인스턴스가있다. 상황과 치료의 품질에 따라 긴 뼈 골절의 2-30% 비 노조 3,5의 결과로 실패합니다. 정의, 가관절, 크기의 중요한 또는 비 노조 뼈 부상에 대한 몇 가지 논쟁이 남아있는 동안 일반적으로 피사체 (6)의 자연 수명 기간 동안 치유되지 않는 상처를 의미한다. 실험 목적을 위해,이 기간은 평균 크기의 뼈 상해 완전히 치유에 필요한 평균 시간으로 단축된다. 비 노조 뼈의 병변은 NUM 발생erous 이유,하지만 주요 요인으로 인한 질병 또는 7 세에 비판적 크기의 차이, 감염, 가난한 혈관 신생, 흡연, 또는 억제 osteoregenerative 용량의 결과로 극단적 인 외상을 포함한다. 비 조합이 성공적으로 처리 된 경우에도, 그 손상의 유형 및 사용 방법 (8)에 따라, 프로 시저 당 60,000 달러를 초과하는 비용이있다.

적당한 경우, 자가골 이식술가 사용된다. 이 전략은 부상의 사이트에 공여 부위와 이식에서 뼈의 회복을 포함한다. 이 방법은 매우 효과적이지만, 가능한 도너 – 유도 된 뼈의 용적에 제한이 있으며 절차는 많은 환자에서 지속적인 통증 9,10 결과 추가적인 수술을 포함한다. 또한,자가 골 이식술의 효능, 환자의 건강 의존한다. 합성 물질 또는 처리 사체 뼈로 만든 뼈 대체는 11-13 풍부하게 사용할 수 있습니다,하지만 그들은 하불량한 숙주 세포 접착 성이 감소 osteoconductivity 및 면역 거부 (14)에 대한 전위를 포함 상당한 제한을했습니다. 안전하고 효과적이고 널리 사용되어 골 재생 기술이 시급히 요구된다.

뼈 재생 전략을 개선하기 위해 우리의 능력을 시험 동물에 심각한 뼈 외상을 모방 할 수있는 능력에 결정적으로 의존하지만, 큰 뼈 병변의 생성 및 안정화 기술적 도전이다. 대부분의 경우, 심각한 긴 뼈 외상은 자연적으로 치유되지 않습니다 결함을 구축하여 실험적으로 모방한다. 그것은 15 종에 따라 다를 수 있지만, 이는 뼈의 단면 (16)의 1.5 배보다 큰 직경 뼈 세그먼트의 완전한 제거에 의해 달성된다. 뼈 골절 후 연부의 적절한 배향을 유지하고 이동을 허용하기 위해 금속 임플란트로 안정화된다. 때문에 작은 크기와의 취약성에긴 뼈, 마우스 등 병변의 설립은 대부분의 연구 그룹의 기능을 능가한다. 따라서, 긴 골 결손 모델 쥐와 큰 동물에 국한되어있다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 마우스들은 인간 유전자 변형 세포와 조직을 거부하지 않기 때문에 면역 타협 한 균주로 육종 할 수 있다는 점에서 상당한 이점을 연구 수득.

인간 세포 기반 응용 프로그램의 면역 손상 쥐들이 생리 학적으로 집에 쉽게, 잘 특성화 때문에 작업하기 매력, 비용 대비 효과, 쉽게 조직 학적, 방사선 학적 및 분석. 가장 중요한 면역 손상 마우스는 인간을 포함한 다른 종의 세포를 거부하지 않는다는 것입니다. 그들의 작은 크기도 세포 또는 응용 프로그램 정형 외과에서 실험 비계의 볼륨의 아주 작은 숫자의 테스트를 허용합니다. 몇몇 뮤린 모델은 정형 뼈 안정성 17,18 다양한 정도의 여유도보고되었다. 그 정기적 복용연골 치유가 19을보고 하였지만 이러한 외고정 고정판과 같은 매우 높은 안정성 수준을 초래할 MS 주로 intramembranous 골화 치유. 대조적으로, 이러한 비 고정 또는 부분적 수질 고정 핀을 이용하는 것과 같은 일부 마이크로 및 / 또는 매크로 움직임을 허용 자들은 일반적으로 (20, 21)의 연골 내 골화 우세 치료한다. 지연 유합 또는 긴 뼈의 불유합의 결함으로 인해 필요한 안정화의 추가 수준에 마우스를 달성하는 것이 특히 어렵다. 그러나 접근 방법은 연동 손톱 수질 핀, 잠금 판과 외고정 (22)를 포함하여,보고되었다. 이러한 시스템은 일반적으로 잘 작동하지만 그들의 복잡한 디자인들이 설치가 기술적으로 어려울 수 있습니다 주어. 예를 들어, 가르시아 등. (23)는 마우스에서 사용하기위한 우아한 연동 핀 시스템을 고안 있지만 절차는 두 개의 분리 된 부위에서 절개를 포함s와 대퇴골의 광범위한 수정은 핀을 수용 할 수 있습니다. 이러한 절차는 해부 현미경 하에서 수행 하였다.

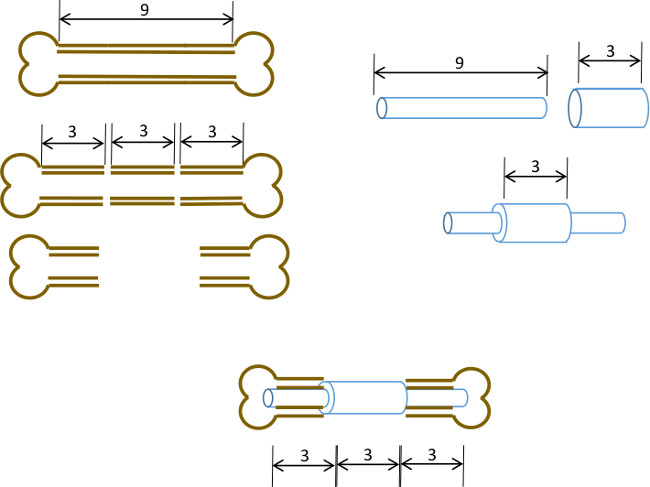

여기서, 우리는 3mm 골 결손의 폐쇄를 방지하고 또한 결함의 원래 가장자리를 묘사하기위한 중앙 칼라와 간단한 대퇴 골수의 핀을 설명합니다. 핀 자체가 뼈에 고정되어 있지 않은 동안, 충분한 간섭 골수 공동 결과 핀 직경 리머의 정확한 크기는 비틀림 운동 (도 1)을 최소화한다. 근친 연령, 성별 및 유사한 변형 마우스의 신중한 선택으로, 방사선 학적 결과는 용이하게 평가할 수있다 재현성 비후성 비 uniondefect 22이다. 또한 관심의 영역을 재현성 드 노보 골 형성 및 histomorphological 파라미터 측정 용 마이크로 컴퓨터 단층 촬영 (μCT) 이후에 정의 될 수있다. 핀은 쉽게 사용할 수있는 도구를 사용하여 우리의 실험실에서 프로토 타입했다.

그림 1 : 실험 원리 분절 결함 모델의 도식 요약.. 9-10mm 쥐의 대퇴골의 중심 3mm 세그먼트 (왼쪽) 수술로 절제한다. 3mm 길이, 19 게이지 수술 스틸 튜브는 정확한 센터 (오른쪽)에 길이 9mm, 22 G 스테인리스 스틸 관을 통해 전달 및 접착제로 고정되어 있습니다. 얻어진 핀 뼈 3mm 세그먼트 교체 19 G 칼라 (이하, 센터)과 대퇴골 근위부와 원위부 나머지 부분 운하 수질에 장착되어있다.

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

여기서, 우리는 표준 실험실 및 수의 장비를 이용하여 쥐 대퇴골의 임계 크기 핀 – 안정화 된 결함을 생성하는 간단한 방법을 설명한다. 핀과 수술 자체의 조립은 연습이 필요하지만, 잘 잘 훈련 된 생물 의학 연구 과학자 또는 수의사의 기능에 있습니다.

핀은 외고정 또는 연동 나사를 사용 더 복잡한 방법보다 절차가 기술적으로 가능하고, 추가로 고정하지 않고 뼈 속질에 ?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

우리는이 기술의 개발 과정에서 자신의 귀중한 조언과 지원, 비교 의학, 사원, 텍사스의 스콧 & 화이트 병원 부서의 직원과 수의사 감사합니다. 이 작품은 재생 의학 프로그램 자금 연구소, 스콧 & 화이트 RGP 보조금 # 90172, NIH 2P40RR017447-07 및 NIH R01AR066033-01 (NIAMS)에 의해 부분적으로 투자되었다. 우리는 원고를 교정에 대한 박사 수잔 Zeitouni 감사합니다.

Materials

| Name of Equipment/Material* | Company | Catalog or model | Notes |

| Pin Assembly | |||

| Dremel rotary tool | Dremel | 8220 | or equivalent |

| Heavy duty cut off wheel | Dremel | 420 | |

| Surgical tubing 19G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMZ8LY | OD 1.07mm, ID 0.889mm |

| Surgical tubing 21G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMZ8YQ | OD 0.82mm, ID 0.635mm |

| Surgical tubing 22G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMYLZS | OD 0.719mm, ID 0.502mm |

| Surgical tubing 23G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FN0SY0 | OD 0.643mm, ID 0.444mm |

| Cyanoacrylate adhesive | Loctite | 1365882 | |

| Emery disc | Dremel | 413 | |

| Rubber polishing point | Dremel | 462 | |

| Felt polishing disc | Dremel | 414 | |

| Gelatin sponge | Surgifoam/Ethicon | 1974 | |

| Punch biopsy cutter | Miltex | 33-34 | |

| Surgery/post-operative | |||

| Warm pad and circulator pump | Stryker/Thermocare | TP700, TP700C, TPP722 | |

| Coverage quaternary spray | Steris | 1429-77 | |

| Bead sterilizer | Germinator/CellPoint Scentific | Germinator 500 | |

| Anesthesia system | VetEquip Inc | 901806 or 901807/901809 | |

| Isofluorane anesthetic | VETone/MWI | 501017, 502017 | |

| Surgical disinfectant | Chloraprep/CareFusion | 260449 | |

| Surgical tools | Fine Science Tools | various | recommend German made |

| Face protection | Splash Shield | 4505 | |

| Rechargable high speed drill | Fine Science Tools | 18000-17 | |

| Diamond cutting wheel | Strauss Diaiond | 361.514.080HP | |

| Absorbable sutures | Covidien | UM-213 | |

| Outer sutures | Ethicon | 668G | or equivalent |

| Vetbond | 3M | 1469SB | or equivalent |

| Hydration gel | Clear H2O | 70-01-1082 | |

| Diet gel | Clear H2O | 72-01-1062 | |

| Buprenorphine | Reckitt and Benckser | 12496-0757-01 | controlled substance |

| Mouse igloos | Bio Serv | K3328, 3570,3327 | |

| Euthanasia cocktail | Euthasol/Virbac | 710101 | controlled substance |

| Analysis | |||

| Live animal imager | Orthoscan | FD Pulse | or equivalent |

| Micro-CT unit and software | Bruker | Skyscan1174 | or equivalent |

| Sealing film/Parafilm M | VWR or Fisher | 100501-338, S37441 | |

| *Generic sources are suitable for all other items such as gause, drapes, protective clothing, animal care equipment. | |||

References

- Brinker, M. R., O’Connor, D. P. The incidence of fractures and dislocations referred for orthopaedic services in a capitated population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 86, 290-297 (2004).

- Cheung, C. The future of bone healing. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 22, 631-641 (2005).

- Rosemont, I. L. . United States Bone and Joint Decade: The burden of musculoskeletal diseases and musculoskeletal injuries. , (2008).

- Tzioupis, C., Giannoudis, P. V. Prevalence of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 38, S3-S9 (2007).

- Marsh, D. Concepts of fracture union, delayed union, and nonunion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. , S22-S30 (1998).

- Spicer, P. P., et al. Evaluation of bone regeneration using the rat critical size calvarial defect. Nat Protoc. 7, 1918-1929 (2012).

- Green, E., Lubahn, J. D., Evans, J. Risk factors, treatment, and outcomes associated with nonunion of the midshaft humerus fracture. J Surg Orthop Adv. 14, 64-72 (2005).

- Kanakaris, N. K., Giannoudis, P. V. The health economics of the treatment of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 38, S77-S84 (2007).

- Dimitriou, R., Mataliotakis, G. I., Angoules, A. G., Kanakaris, N. K., Giannoudis, P. V. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 42, S3-S15 (2011).

- Boer, H. H. The history of bone grafts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. , 292-298 (1988).

- Aro, H. T., Aho, A. J. Clinical use of bone allografts. Ann Med. 25, 403-412 (1993).

- Burstein, F. D. Bone substitutes. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 37, 1-4 (2000).

- Kao, S. T., Scott, D. D. A review of bone substitutes. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 19, 513-521 (2007).

- Boden, S. D. Overview of the biology of lumbar spine fusion and principles for selecting a bone graft substitute. Spine. (Phila Pa 1976). 27, S26-S31 (1976).

- Hollinger, J. O., Kleinschmidt, J. C. The critical size defect as an experimental model to test bone repair materials). J Craniofac Surg. 1, 60-68 (1990).

- Key, J. The effect of local calcium depot on osteogenesis and healing of fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Am). 16, 176-184 (1934).

- Holstein, J. H., et al. Advances in the establishment of defined mouse models for the study of fracture healing and bone regeneration). J Orthop Trauma. 23, S31-S38 (2009).

- Histing, T., et al. Small animal bone healing models: standards, tips, and pitfalls results of a consensus meeting. Bone. 49, 591-599 (2011).

- Cheung, K. M., et al. An externally fixed femoral fracture model for mice. J Orthop Res. 21, 685-690 (2003).

- Hiltunen, A., Vuorio, E., Aro, H. T. A standardized experimental fracture in the mouse tibia. J Orthop Res. 11, 305-312 (1993).

- Manigrasso, M. B., O’Connor, J. P. Characterization of a closed femur fracture model in mice. J Orthop Trauma. 18, 687-695 (2004).

- Garcia, P., et al. Rodent animal models of delayed bone healing and non-union formation: a comprehensive review. Eur Cell Mater. 26, 1-12 (2013).

- Garcia, P., et al. Development of a reliable non-union model in mice. J Surg Res. 147, 84-91 (2008).

- Flecknell, P. A. The relief of pain in laboratory animals. Lab Anim. 18, 147-160 (1984).

- . . Guidelines on the Euthanasia of Animals. , (2013).

- Neill, K. R., et al. Micro-computed tomography assessment of the progression of fracture healing in mice. Bone. 50, 1357-1367 (2012).

- Bagi, C. M., et al. The use of micro-CT to evaluate cortical bone geometry and strength in nude rats: correlation with mechanical testing, pQCT and DXA. Bone. 38, 136-144 (2006).

- Hadjiargyrou, M., et al. Transcriptional profiling of bone regeneration. Insight into the molecular complexity of wound repair. J Biol Chem. 277, 30177-30182 (2002).

- Clough, B. H., et al. Bone regeneration with osteogenically enhanced mesenchymal stem cells and their extracellular matrix proteins. J Bone Miner Res. , (2014).

- Lu, C., et al. Cellular basis for age-related changes in fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 23, 1300-1307 (2005).

- Jepsen, K. J., et al. Genetic variation in the patterns of skeletal progenitor cell differentiation and progression during endochondral bone formation affects the rate of fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 23, 1204-1216 (2008).

- Thayer, T. C., Wilson, S. B., Mathews, C. E. Use of nonobese diabetic mice to understand human type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 39, 541-561 (2010).

- Jee, W. S., Yao, W. Overview: animal models of osteopenia and osteoporosis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 1, 193-207 (2001).