マウスの簡単な重要なサイズの大腿欠陥モデル

Summary

Animal models are frequently employed to mimic serious bone injury in biomedical research. Due to their small size, establishment of stabilized bone lesions in mice are beyond the capabilities of most research groups. Herein, we describe a simple method for establishing and analyzing experimental femoral defects in mice.

Abstract

While bone has a remarkable capacity for regeneration, serious bone trauma often results in damage that does not properly heal. In fact, one tenth of all limb bone fractures fail to heal completely due to the extent of the trauma, disease, or age of the patient. Our ability to improve bone regenerative strategies is critically dependent on the ability to mimic serious bone trauma in test animals, but the generation and stabilization of large bone lesions is technically challenging. In most cases, serious long bone trauma is mimicked experimentally by establishing a defect that will not naturally heal. This is achieved by complete removal of a bone segment that is larger than 1.5 times the diameter of the bone cross-section. The bone is then stabilized with a metal implant to maintain proper orientation of the fracture edges and allow for mobility.

Due to their small size and the fragility of their long bones, establishment of such lesions in mice are beyond the capabilities of most research groups. As such, long bone defect models are confined to rats and larger animals. Nevertheless, mice afford significant research advantages in that they can be genetically modified and bred as immune-compromised strains that do not reject human cells and tissue.

Herein, we demonstrate a technique that facilitates the generation of a segmental defect in mouse femora using standard laboratory and veterinary equipment. With practice, fabrication of the fixation device and surgical implantation is feasible for the majority of trained veterinarians and animal research personnel. Using example data, we also provide methodologies for the quantitative analysis of bone healing for the model.

Introduction

これは、治療骨折を有する患者のために外科的に50万手続きは骨移植片2の使用を含む。米国の人口の半分は65 1歳までに骨折を経験していると推定されており、この数は、ますます高齢化、人口3に上昇すると予想されている。骨が完全に瘢痕なしに治癒する能力を有するいくつかの臓器の一つであるが、プロセスは3,4失敗する場合がある。状況や処理の品質に応じて、長骨骨折の2〜30%は、非組合3,5で得られた、失敗。定義、偽関節、大きさのクリティカルまたは非組合骨損傷上のいくつかの議論が残っているものの、一般的に被検体6の自然な寿命にわたって治癒しない怪我を指します。実験目的のために、この期間は、平均的なサイズの骨損傷の完全な治癒に必要な平均時間に短縮される。非組合骨病変はNUMのために起こるerousの理由が、主な要因は、原因疾患や年齢7に批判的にサイズのギャップ、感染、貧しい血管新生、タバコの使用、または阻害osteoregenerative容量になり、極端な外傷が含まれる。非組合が正常に処理されたとしても、それは損傷の種類と8を採用アプローチに応じて、手順6万ドルを超える費用がかかる。

中程度の場合には、自家骨髄移植が用いられる。この戦略は、損傷部位でのドナー部位および移植から骨の回復を伴う。このアプローチは非常に有効であるが、利用可能なドナー由来の骨の量は限られており、手順は、多くの患者9,10において持続性疼痛をもたらす追加の手術を伴う。また、自家骨移植片の有効性は、患者の健康状態に依存する。合成材料または処理死体の骨から作られた代用骨は11-13豊富に利用可能ですが、彼 らはヘクタール乏しい宿主細胞の接着性、骨伝導性減少、および免疫拒絶14の可能性を含め、重大な制限VEの。安全で、効果的であり、広く利用可能な骨再生技術が緊急に必要とされている。

骨再生の戦略を改善する当社の能力は、試験動物に深刻な骨の外傷を模倣する能力に決定的に依存しているが、大きな骨病変の発生と安定化は技術的に困難である。ほとんどの場合、深刻な長骨の外傷が自然治癒しない欠陥を確立することによって実験的に模倣される。それは種15によって変化し得るが、これは骨の断面16の直径の1.5倍よりも大きい骨セグメントを完全に除去することによって達成される。骨は、その後骨折エッジの適切な配向を維持し、移動性を可能にするために、金属インプラントで安定化される。その小さなサイズとの脆弱性に起因する彼らの長い骨は、マウスではそのような病変の確立が最も研究グループの能力を超えている。このように、長骨欠損モデルは、ラットおよび大型動物に限定される。それにもかかわらず、マウスは、それらが遺伝的に修飾されたヒト細胞および組織を拒絶しない、免疫不全株として育種することができるという点で、重要な研究の利点をもたらす。

彼らは生理的によく特徴付けているため、ヒト細胞ベースのアプリケーションでは、免疫不全マウスはで動作するように魅力的で、家に簡単に、効果的なコスト、簡単に放射線学的および組織学的に分析した。最も重要な免疫不全マウスは、ヒトを含む異なる種からの細胞を拒絶しないことである。その小さなサイズはまた、細胞または整形外科用途で実験的な足場の体積の非常に少数のテストを可能にします。いくつかのマウスモデルが整形外科用骨安定17,18の様々な程度を与えることが報告されている。これらのsyste軟骨内の治癒が19に報告されているが、外部固定器とロッキングプレートとしての安定性の非常に高いレベルをもたらすmsが主に膜内骨化によって治癒する。対照的に、未修正または部分的に固定された髄ピンを用いたものなど、いくつかのミクロおよび/ またはマクロ運動を可能にするものは、一般的に軟骨内骨化20,21が優勢で治癒する。長骨の遅延組合や非組合欠陥が必要な安定化の余分なレベルに起因したマウスで達成することが特に困難である。しかし、多くのアプローチが、プレートと外部固定器22をロックする、インターロック爪と髄ピンを含む、報告されている。これらのシステムは、一般的にはうまく動作しますが、その複雑な設計与えられた彼らは、インストールすることが技術的に挑戦することができます。例えば、ガルシアら 23は、マウスにおける使用のための優雅なインターロックピン方式を考案したが、手順は、2つの別々の部位における切開を伴いピンを収容するための大腿骨の広範な修正。これらの手順は、解剖顕微鏡下で行った。

ここで、我々は、3ミリメートルの骨欠損の閉鎖を防止し、また、欠陥のオリジナルのエッジを描くように設計され、中央襟付きのシンプルな大腿骨髄ピンについて説明します。ピンは、骨自体に固定されなかったが、十分な干渉髄腔結果のピン径、およびリーマの正確なサイジングがねじれ運動( 図1)を最小化する。近交系、年齢、性別及び歪みを一致させたマウスを慎重に選択すると、結果は簡単に放射線学的に評価することが可能で再現性の高い肥大非uniondefect 22です。また、関心領域は、再現デノボ骨形成および組織形態学的パラメータを測定するためのマイクロコンピュータ断層撮影(μCT)の後に定義することができる。ピンは、容易に入手可能なツールを使用して、我々の研究室で試作された。

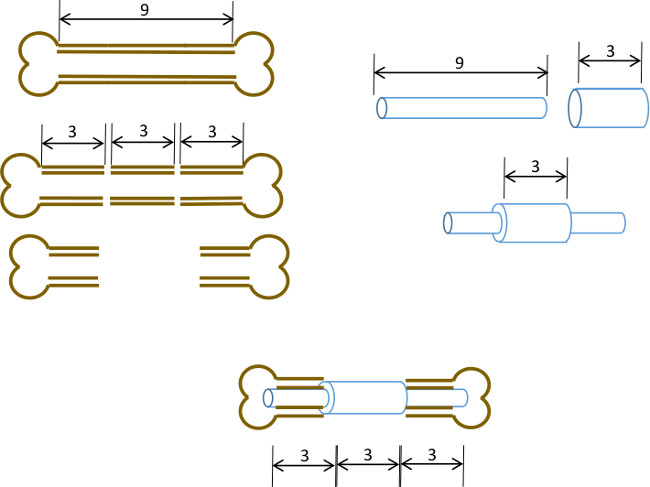

図1:実験原理分節欠損モデルの図的要約。 9〜10ミリメートルマウス大腿骨の中央の3ミリメートルのセグメントは、( 左 )外科的に切除されている。長さ3mm、19ゲージの外科用鋼管は、正確な中心( 右 )での長い9ミリメートル、22 Gステンレス管の上を通過し、接着剤で固定されている。得られたピンは、骨の3mmのセグメントを置き換える19 Gのカラー( 以下、センター )と大腿骨の残りの近位および遠位部分の髄運河に嵌め込まれている。

Protocol

Representative Results

Discussion

ここで、我々は、標準的な実験および獣医装置を使用して、マウスの大腿骨の臨界サイズのピンで安定化された欠陥を生成する簡単な方法を説明する。ピンのアセンブリと、外科的処置自体は練習が必要ですが、それはよくよく訓練された生物医学研究者や獣医師の能力の範囲内である。

ピンは、技術的により実現可能な外部固定またはインターロックねじを採用し、?…

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

私たちは、この技術の開発中に彼らの貴重な助言と支援のために、比較医学、寺院、テキサス州のスコット&ホワイト病院部門のスタッフや獣医師に感謝します。この作品は、再生医療プログラムの資金のための研究所、スコット&ホワイトRGP助成#90172、NIH 2P40RR017447-07及びNIH R01AR066033-01(NIAMS)によって部分的に資金を供給した。私たちは、原稿を校正するための博士スザンヌ·ゼイトゥーニーに感謝。

Materials

| Name of Equipment/Material* | Company | Catalog or model | Notes |

| Pin Assembly | |||

| Dremel rotary tool | Dremel | 8220 | or equivalent |

| Heavy duty cut off wheel | Dremel | 420 | |

| Surgical tubing 19G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMZ8LY | OD 1.07mm, ID 0.889mm |

| Surgical tubing 21G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMZ8YQ | OD 0.82mm, ID 0.635mm |

| Surgical tubing 22G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FMYLZS | OD 0.719mm, ID 0.502mm |

| Surgical tubing 23G | Small Parts (Amazon) | B000FN0SY0 | OD 0.643mm, ID 0.444mm |

| Cyanoacrylate adhesive | Loctite | 1365882 | |

| Emery disc | Dremel | 413 | |

| Rubber polishing point | Dremel | 462 | |

| Felt polishing disc | Dremel | 414 | |

| Gelatin sponge | Surgifoam/Ethicon | 1974 | |

| Punch biopsy cutter | Miltex | 33-34 | |

| Surgery/post-operative | |||

| Warm pad and circulator pump | Stryker/Thermocare | TP700, TP700C, TPP722 | |

| Coverage quaternary spray | Steris | 1429-77 | |

| Bead sterilizer | Germinator/CellPoint Scentific | Germinator 500 | |

| Anesthesia system | VetEquip Inc | 901806 or 901807/901809 | |

| Isofluorane anesthetic | VETone/MWI | 501017, 502017 | |

| Surgical disinfectant | Chloraprep/CareFusion | 260449 | |

| Surgical tools | Fine Science Tools | various | recommend German made |

| Face protection | Splash Shield | 4505 | |

| Rechargable high speed drill | Fine Science Tools | 18000-17 | |

| Diamond cutting wheel | Strauss Diaiond | 361.514.080HP | |

| Absorbable sutures | Covidien | UM-213 | |

| Outer sutures | Ethicon | 668G | or equivalent |

| Vetbond | 3M | 1469SB | or equivalent |

| Hydration gel | Clear H2O | 70-01-1082 | |

| Diet gel | Clear H2O | 72-01-1062 | |

| Buprenorphine | Reckitt and Benckser | 12496-0757-01 | controlled substance |

| Mouse igloos | Bio Serv | K3328, 3570,3327 | |

| Euthanasia cocktail | Euthasol/Virbac | 710101 | controlled substance |

| Analysis | |||

| Live animal imager | Orthoscan | FD Pulse | or equivalent |

| Micro-CT unit and software | Bruker | Skyscan1174 | or equivalent |

| Sealing film/Parafilm M | VWR or Fisher | 100501-338, S37441 | |

| *Generic sources are suitable for all other items such as gause, drapes, protective clothing, animal care equipment. | |||

References

- Brinker, M. R., O’Connor, D. P. The incidence of fractures and dislocations referred for orthopaedic services in a capitated population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 86, 290-297 (2004).

- Cheung, C. The future of bone healing. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 22, 631-641 (2005).

- Rosemont, I. L. . United States Bone and Joint Decade: The burden of musculoskeletal diseases and musculoskeletal injuries. , (2008).

- Tzioupis, C., Giannoudis, P. V. Prevalence of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 38, S3-S9 (2007).

- Marsh, D. Concepts of fracture union, delayed union, and nonunion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. , S22-S30 (1998).

- Spicer, P. P., et al. Evaluation of bone regeneration using the rat critical size calvarial defect. Nat Protoc. 7, 1918-1929 (2012).

- Green, E., Lubahn, J. D., Evans, J. Risk factors, treatment, and outcomes associated with nonunion of the midshaft humerus fracture. J Surg Orthop Adv. 14, 64-72 (2005).

- Kanakaris, N. K., Giannoudis, P. V. The health economics of the treatment of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 38, S77-S84 (2007).

- Dimitriou, R., Mataliotakis, G. I., Angoules, A. G., Kanakaris, N. K., Giannoudis, P. V. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 42, S3-S15 (2011).

- Boer, H. H. The history of bone grafts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. , 292-298 (1988).

- Aro, H. T., Aho, A. J. Clinical use of bone allografts. Ann Med. 25, 403-412 (1993).

- Burstein, F. D. Bone substitutes. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 37, 1-4 (2000).

- Kao, S. T., Scott, D. D. A review of bone substitutes. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 19, 513-521 (2007).

- Boden, S. D. Overview of the biology of lumbar spine fusion and principles for selecting a bone graft substitute. Spine. (Phila Pa 1976). 27, S26-S31 (1976).

- Hollinger, J. O., Kleinschmidt, J. C. The critical size defect as an experimental model to test bone repair materials). J Craniofac Surg. 1, 60-68 (1990).

- Key, J. The effect of local calcium depot on osteogenesis and healing of fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Am). 16, 176-184 (1934).

- Holstein, J. H., et al. Advances in the establishment of defined mouse models for the study of fracture healing and bone regeneration). J Orthop Trauma. 23, S31-S38 (2009).

- Histing, T., et al. Small animal bone healing models: standards, tips, and pitfalls results of a consensus meeting. Bone. 49, 591-599 (2011).

- Cheung, K. M., et al. An externally fixed femoral fracture model for mice. J Orthop Res. 21, 685-690 (2003).

- Hiltunen, A., Vuorio, E., Aro, H. T. A standardized experimental fracture in the mouse tibia. J Orthop Res. 11, 305-312 (1993).

- Manigrasso, M. B., O’Connor, J. P. Characterization of a closed femur fracture model in mice. J Orthop Trauma. 18, 687-695 (2004).

- Garcia, P., et al. Rodent animal models of delayed bone healing and non-union formation: a comprehensive review. Eur Cell Mater. 26, 1-12 (2013).

- Garcia, P., et al. Development of a reliable non-union model in mice. J Surg Res. 147, 84-91 (2008).

- Flecknell, P. A. The relief of pain in laboratory animals. Lab Anim. 18, 147-160 (1984).

- . . Guidelines on the Euthanasia of Animals. , (2013).

- Neill, K. R., et al. Micro-computed tomography assessment of the progression of fracture healing in mice. Bone. 50, 1357-1367 (2012).

- Bagi, C. M., et al. The use of micro-CT to evaluate cortical bone geometry and strength in nude rats: correlation with mechanical testing, pQCT and DXA. Bone. 38, 136-144 (2006).

- Hadjiargyrou, M., et al. Transcriptional profiling of bone regeneration. Insight into the molecular complexity of wound repair. J Biol Chem. 277, 30177-30182 (2002).

- Clough, B. H., et al. Bone regeneration with osteogenically enhanced mesenchymal stem cells and their extracellular matrix proteins. J Bone Miner Res. , (2014).

- Lu, C., et al. Cellular basis for age-related changes in fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 23, 1300-1307 (2005).

- Jepsen, K. J., et al. Genetic variation in the patterns of skeletal progenitor cell differentiation and progression during endochondral bone formation affects the rate of fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 23, 1204-1216 (2008).

- Thayer, T. C., Wilson, S. B., Mathews, C. E. Use of nonobese diabetic mice to understand human type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 39, 541-561 (2010).

- Jee, W. S., Yao, W. Overview: animal models of osteopenia and osteoporosis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 1, 193-207 (2001).